If the body is deficient in thyroid hormones, there may be a reduction in basal metabolic rate with multiple clinical consequences. Hypothyroidism is often acquired due to an autoimmune genesis, then occurs in adulthood and requires lifelong substitution with L-thyroxine.

Symptoms such as fatigue, lethargy, cold intolerance, and weight gain may indicate hypothyroidism (Tab. 1). This thyroid hormone deficiency is present in about 5% of the European population, with women and the elderly being more frequently affected. The disease is differentiated into primary (autoimmune genesis), secondary (TSH deficiency) and tertiary (TRH deficiency) hypothyroidism. As a rule, a primary form is present, which in turn is subdivided into manifest and latent hypothyroidism. Dysregulation of the immune system leads to the formation of antibodies measurable in the blood, which impair the function of the thyroid gland and in the long term lead to extensive loss of organ function or destruction of the gland. Hypothyroidism is diagnosed by an excessively high level of the regulatory hormone TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) with a simultaneous decrease in one or both of the levels of the thyroid hormones free T3 (triiodothyronine) and free T4 (levothyroxine). A latent manifestation is when only the TSH level is elevated, but the other values are still within the normal range.

When testing should be done is highly controversial and there is no international consensus on which indications and how often diagnosis or screening for thyroid dysfunction should be done. Symptom-oriented testing is recommended, although this leaves a lot of room for maneuver. This is because the symptoms attributed to hypothyroidism are generally common in the population. In addition, TSH levels are often somewhat elevated in obesity, for example. A decrease in TSH is then observed with weight loss. It is assumed here that leptin, among other things, exerts an effect on TSH levels. Conversely, current observations do not show that latent hypothyroidism always leads to weight gain and that adequate therapy will reduce this weight again.

Root Cause Analysis

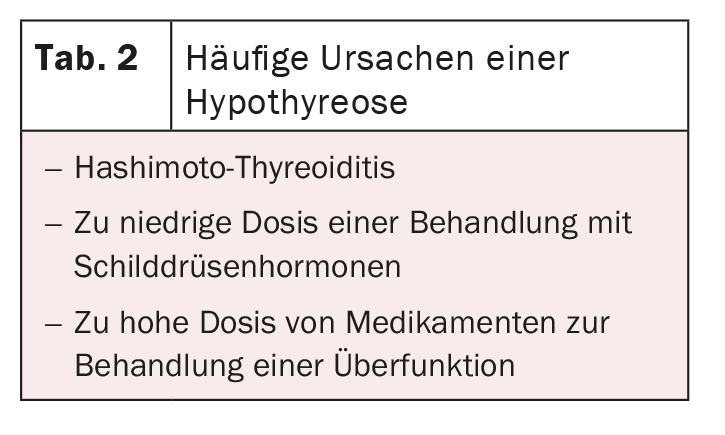

The most common cause of hypothyroidism is Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (Tab. 2). Therefore, thyroperoxidase antibodies (TPO-AK) and thyroglobulin antibodies (Tg-AK) should always be determined in addition to TSH. TPO-AK are positive in 90-95%, Tg-AK in 60-80%. Especially a particularly high AK value seems to correlate with the activity of the disease. A quarter of the patients also have another autoimmune disease, so that screening for Addison’s disease, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, or celiac disease seems reasonable. Other causes of hypothyroidism may include iatrogenic causes after thyroid surgery or radioiodine therapy, in addition to poor control in hyperthyroidism.

Quality of life severely limited

In contrast to patients with latent hypothyroidism, the quality of life is significantly reduced in those with manifest hypothyroidism. In addition to the known symptoms, study data seem to suggest that increasing severity of the disease with very high TSH is associated with increased cardiovascular risk. In addition, hypothyroidism affects lipid metabolism, which is characterized by, among other things, higher LDL cholesterol and higher triglycerides. Therefore, adequate therapy management is indicated.

If hypothyroidism is detected for the first time, no treatment should be given initially. Only when the diagnosis is confirmed after a laboratory control 2-3 months later, a therapy with L-thyroxine can be initiated depending on the age as well as the symptoms. The recommended dosage for latent hypothyroidism is approximately 1.5 µg/kg/day, which corresponds to approximately 75-100 µg in women and approximately 100-125 µg in men. Serum TSH should be after approximately two months, aiming for a target range of 0.4-2.5 mU/L.

Further reading:

- www.endokrinologie.net/krankheiten-schilddruese-unterfunktion.php

- www.medix.ch/wissen/guidelines/stoffwechselkrankheiten/schilddruesenerkrankungen

- Pilz S, Theiler-Schwetz V, Malle O, et al: Hypothyroidism: guidelines, new evidence and clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2020; 13: 88-95.

CARDIOVASC 2021; 20(1): 20