To perceive one’s own feelings, thoughts, impulses to act and sensations without being under pressure to act – that is the goal of mindfulness. The method is particularly suitable for relapse prevention in depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders.

The concept of mindfulness originates from Buddhist meditation practice and, according to Jon Kabat-Zinn’s formulation, can be understood as an orientation of attention to the present moment that is intentional and done in a non-judgmental way [1]. This state of mind is distinctly different from the “everyday,” in which there is often a diffusion of attention and a very immediate and intense (emotional and cognitive) evaluation. In everyday terms, a mindful attitude thus refers to doing the things that are happening right now, completely, without being preoccupied with thoughts that lead away from the concrete experience of the moment.

A wandering mind is an unhappy mind

In a large-scale study, Killingsworth and Gilbert [2] used a smartphone survey to collect the ongoing thoughts, feelings, and actions of 2250 people in real time as they went about their daily activities. In this context, 47% of all participants reported that their thoughts were currently occupied with content other than the current action. Participants also reported being happier when they were fully engaged, that is, mentally engaged in what they were doing in the here and now, even when they were doing unpleasant activities. The authors of the study concluded that “the wandering mind is an unhappy mind.” With wandering thoughts, people would have difficulty finding an “anchor” and would be more prone to becoming unhappy or ill.

Effects of mindfulness practice

Mindfulness training promotes conscious awareness and contributes to a higher level of body consciousness and sharpening of our senses. In current research, developing mindfulness is thought to improve emotion regulation [3] and increase awareness of one’s thoughts, feelings, and sensations in the present moment. For example, even naming feelings usually establishes a higher distance from them. This is a basic prerequisite to be able to meet inner experience acceptingly, i.e. to let it happen without having to intervene or counteract it. A mindful attitude is also an important prerequisite for being able to perceive thoughts as such and, if necessary, to distance oneself from their content. Mindfulness can thus be seen as a kind of general self-control technique. Better self-control ultimately opens up the possibility of interrupting current habits and automatisms. As a result, inner impulses can be perceived more quickly, which allows people to decide more consciously from a self-observing attitude, to communicate and to react optimally to the situation.

How is mindfulness related to depression, anxiety, and compulsions?

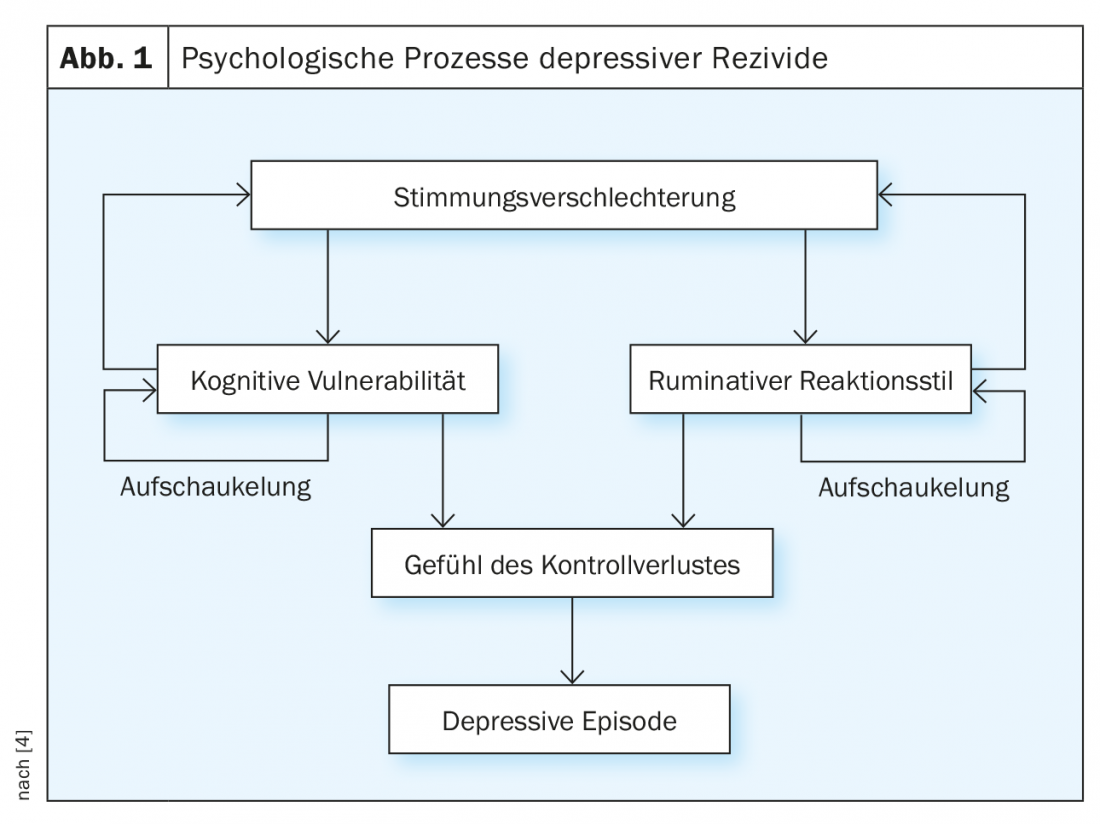

Negative thought and feeling states can easily be reactivated even after a depressive episode has subsided. The triggering factor for relapse is considered to be a mood deterioration, which reactivates dysfunctional thoughts (e.g., “I will harm other people.”), basic assumptions (e.g., “I am a failure.”), and memories of negative events (e.g., “At my last job, I was also fired.”). Ruminative processing when negative moods and thoughts reoccur leads to a depressive buildup, creating a sense of loss of control and potentially promoting depressive development. If, on the other hand, the negative thought patterns can be perceived and interrupted at an early stage, the depressive development can be favorably influenced (Fig. 1).

In the context of pathological anxiety, comparable cognitive processes play an important role. Thus, among other things, basic internal assumptions, memories, or dysfunctional thoughts lead to an internal emotional buildup and can result in the imagining of disaster scenarios that trigger the impairing impulses of escape, control, and avoidance (e.g., “I’m having heart palpitations, I’m going to have a heart attack, I need to call an ambulance”). Without conscious or mindful awareness of these inner processes (e.g. arbitrary conclusions or catastrophizations), they can be interrupted only with difficulty. If, on the other hand, they are perceived mindfully, they can be classified as such and viewed at a distance, and behavior can be directed more consciously and independently of fearful impulses.

Behavior in people with obsessive-compulsive disorder is also characterized by the fact that it is often not focused on the present moment or present danger, but on possible future or past events. Sufferers ruminate about perceived dangerous behaviors in the past (e.g., “Did I leave the lights on at home?”) or ruminate anxiously about the future (e.g., “What if my father dies now because I walked around to the right?”). For compulsions, mindfulness-based intervention focuses primarily on changing attitudes toward obsessive thoughts: perceiving them only as such, without evaluating them or attempting to change them. This makes it possible to interrupt the often long-standing automatism by perceiving the compulsive internal impulses to act as such before the compulsive action is carried out.

In summary, mindfulness practices can help to get out of brooding behavior and worry spirals and to become more aware of one’s own inner behavioral impulses in order to be able to turn to the valuable things in the here and now. They promote:

- the conscious perception of the here and now (as opposed to involuntary thought carousels about the past or the future).

- a non-judgmental attention to one’s own thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations.

- the conscious perception of mood changes, automated cognitions and impulses to act without having to react to them automatically.

Mindfulness in psychotherapy

The practice of mindfulness is currently used in a wide variety of psychotherapeutic procedures. However, there are differences in the extent and type of mindfulness application. Basically, a distinction can be made between mindfulness-based practices and mindfulness-informed approaches. Mindfulness-based practices are grounded in the Buddhist traditions of Jon Kabat-Zinn. Here, Kabat-Zinn’s mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and Segal and colleagues’ mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) are the most widely used practices. Typical mindfulness-informed approaches, for example, the third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy, include acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) or dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). In addition to mindfulness, a whole range of other therapeutic skills are taught. Typically, these approaches do not teach intensive or time-consuming meditation exercises, but rather shorter mindfulness exercises.

Intervention examples

In addition to various mindfulness exercises (e.g., breathing meditation or body scan), questions asked during the therapy session can also represent mindfulness-promoting brief interventions that encourage mindful awareness in the here and now:

- Where are you with your attention right now?

- What are you feeling right now as you sit here?

- Where in your body can you feel this?

- Where are you sitting right now? Where are you looking?

- What do you see? What do you feel? What do you hear?

- What do you feel? What do you taste? What do you smell?

- Describe the feeling, its color, shape, size, …

- Does an urge, an impulse to act, arise in you now?

Research results

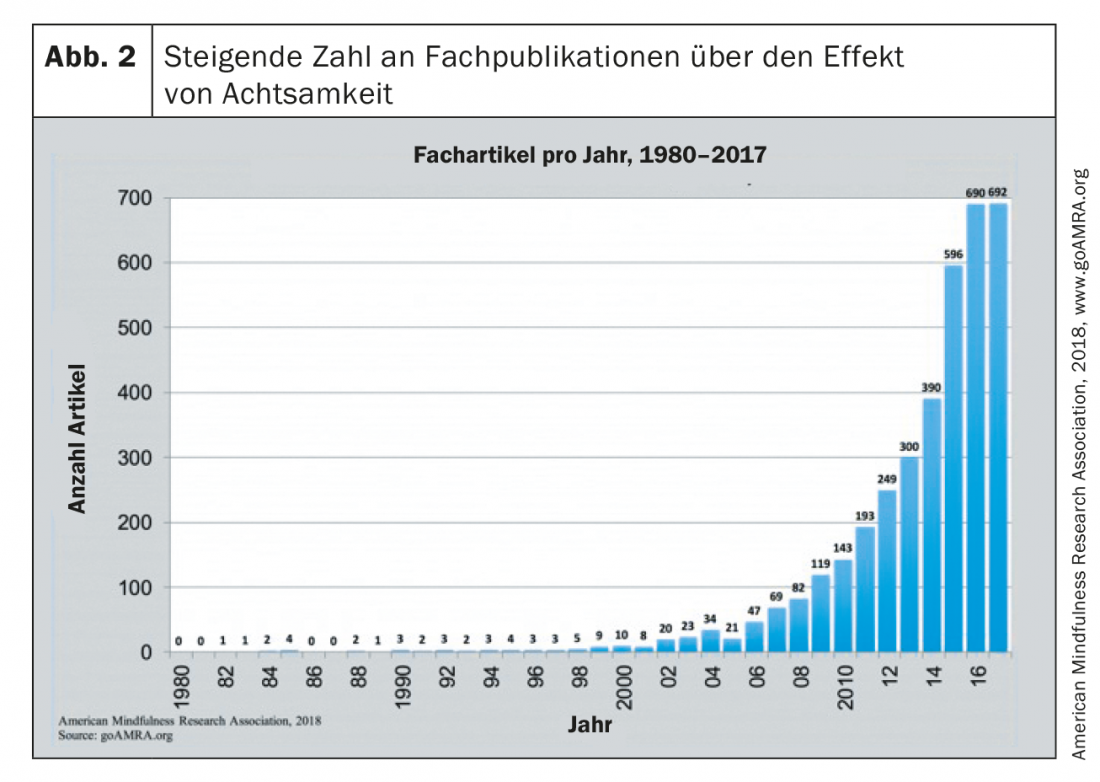

Since the turn of the millennium, mindfulness therapy has also increasingly attracted the interest of empirical research. Since 2000, there has been a marked increase in the number of publications in this field (Fig. 2).

A meta-analysis examining results from 115 studies with a total of 8683 participants was able to show that MBSR and MBCT were associated with improvements in depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress, and selected physical diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, etc. [5]. In healthy adults and children, MBSR and MBCT have also been shown to have a preventive effect; thus, they have been associated with reductions in the experience of stress and other initial psychopathological symptoms that could lead to clinical suffering in the longer term.

How and whether the use of mindfulness-based applications manifests in a neurobiological correlate has been investigated by Lazar and colleagues [6], among others. In this study, changes in brain structures were detected in 20 subjects with extensive meditation experience using MRI scans. Brain areas responsible for sensory processing, attentional regulation, and interoception were thicker in meditating subjects than in matched controls. In another study, activities of brain areas were assessed by functional MRI during exposure to negatively afflicted images [7]. The 24 healthy subjects who performed a brief mindfulness exercise had reduced activity in brain areas responsible for processing emotions (such as the amygdala or parahippocampal gyrus) during viewing of stimuli associated with negative emotions vs. neutral images, compared to the 22 controls without intervention. The results indicate effects of mindfulness training in regulating emotions at a neurobiological level.

Conclusion and outlook

Over the past decade, mindfulness-based therapy for depression, anxiety, and compulsions has evolved from a marginal position in the therapeutic field to a recognized, empirically based practice [8]. MBCT was included in the guidelines under its classic indication, relapse prevention in depression (NICE, S3).

However, despite compelling findings on the efficacy of mindfulness practices, established evidence-based practices for the treatment of depression and anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders should not be neglected. An important future research task is to clarify which procedure is most effective for which patients. Until we know more about this, mindfulness therapies should be viewed as a promising extension of the intervention options available to us, not as a replacement for established treatment approaches.

Take-Home Messages

- Mindfulness promotes improved emotion regulation. In this way, one’s own feelings, thoughts, impulses to act and sensations can be better perceived without having to try to change them.

- MBCT was included in the guidelines under its classic indication, relapse prevention in depression (NICE, S3).

- Until studies clarify which method is most appropriate for which patient, mindfulness therapies should be used as an extension of – not a replacement for – established treatment approaches.

Literature:

- Heidenreich T, Michalak M: Mindfulness and acceptance as principles in psychotherapy. PiD Psychotherapy in Dialogue 2006; 7(3): 235-240.

- Killingsworth MA, Gilbert DT: A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 2010; 330(6006): 932.

- Hayes AM, Feldman G: Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2004; 11(3): 255-262.

- Bohus M, Huppertz M: Mechanisms of action of mindfulness-based psychotherapy. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy 2006; 54(4): 265-276.

- Gotink RA, et al: Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PloS One 2015; 10(4): e0124344.

- Lazar SW, et al: Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport 2005; 16(17): 1893-1897.

- Lutz J, et al: Mindfulness and emotion regulation. An fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013; 9(6): 776-785.

- Hegemann K: Mindfulness therapy for anxiety and depression. InFo Neurol Psychiatr 2018; 16(3): 2-4.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(2): 17-19.