At the 24th Physicians’ Continuing Education Course in Clinical Oncology in St. Gallen was about the risk for venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients with malignant tumors. Not only is it increased per se in this population, but those affected are more likely to suffer recurrences after such an event. The risk for blood coagulation disorders is determined by the following factors: tumor, tumor therapy, non-specific other factors. A good aid for quick orientation is the Khorana risk score.

(red) Tumor patients are three times more likely to suffer fatal pulmonary embolism than patients without malignancies. Up to 15% of all cancer patients experience venous thromboembolism (VTE), one of the leading causes of death in tumor patients. It is not infrequently the first indication of tumor disease. This was pointed out by Dr. med. Thomas Lehmann, head physician at the Center for Laboratory Medicine in St. Gallen. The topic is therefore highly explosive and topical.

VTE as a paraneoplastic syndrome, although less common, is better in focus. In a narrow sense, the term Trousseau’s syndrome means the occurrence of thrombosis and pulmonary embolism as an indicator event of a previously unrecognized tumor disease. The expert emphasized that in idiopathic thrombosis, a limited tumor search (chest x-ray, sonography, blood count, and routine serum values) is indicated.

Tumor patients as a high-risk population

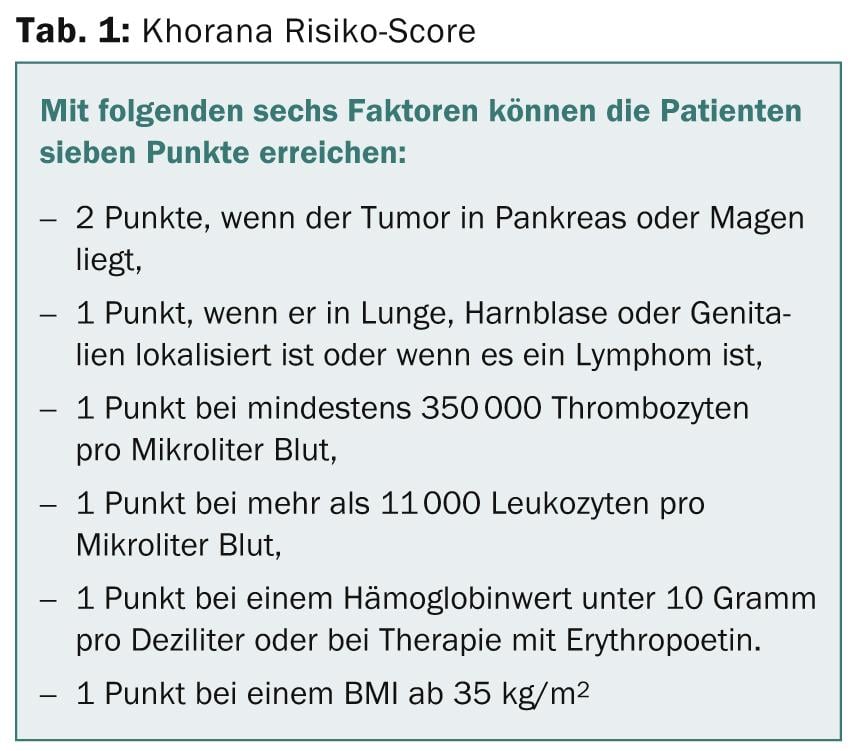

The risk of VTE is not only increased by an underlying pathomechanism. The increased clot activation is possible due to several factors: tumor, tumor therapy, supportive therapy, and nonspecific other factors. In addition, age, comorbidities, infection, gender, ethnicity, obesity, history of VTE, pulmonary and renal disease should be included. It is recommended by professional societies or in their guidelines to classify tumor patients as high-risk patients for VTE. But how can the risk be determined? The Khorana risk score, which Dr. Lehmann presented at the DESO in St. Gallen (Tab. 1), is helpful here. According to Dr. Lehmann, the risk of venous thromboembolism is low only if zero points are reached. One or two points, on the other hand, indicate a medium risk of VTE, and three points or more indicate a high risk.

Prophylaxis?

Drug thromboprophylaxis is established for visceral surgery and gynecologic procedures. Tumor-associated VTE is treated with low-molecular-weight heparin as long-term prophylaxis. Provided the malignancy is active and the risk of bleeding is low, prophylaxis should be continued for up to six months or longer. In contrast, oral anticoagulation does not play a role.

Other events

In 7% of cases, solid tumors lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which is usually characterized by a decrease in the activity of the fibrinolytic system. The driving force is cytokines: IL-6, TNF-α and interleukins of coagulation activation. Consumption of coagulation factors is gradual, rarely fulminant in tumor patients. Thrombocytopenia is the best known sign of DIC.

If the tumor disease is put into remission, DIC disappears at the same time. Routine anticoagulation and, in individual cases, platelet transfusion or factor substitution may be considered as supportive therapy.

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TAM) has an incidence of 2-8% in the high-dose chemotherapy population. Platelet adhesion to endothelial cells often occurs two to nine months after the end of chemotherapy, followed by thrombocytopenia.

Source: 24th Physician Continuing Education Course in Clinical Oncology, February 20-22, 2014, St. Gallen.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2014; 2(3): 25-26.