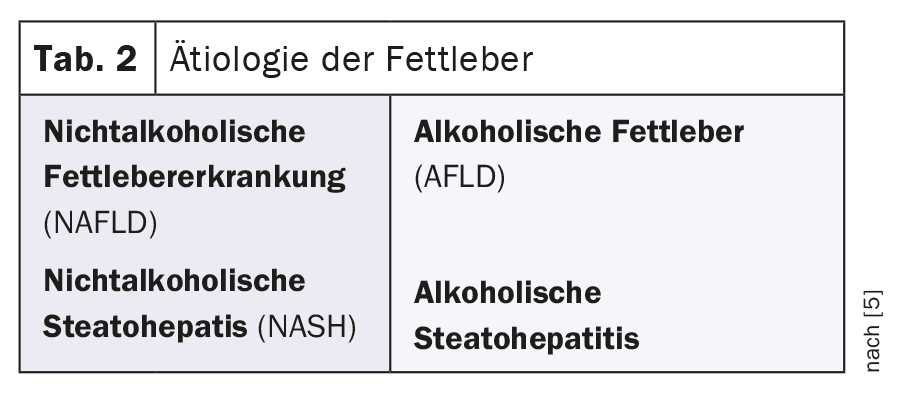

In steatotic liver diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are distinguished from alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD) and alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) from an etiological point of view. The extent of fatty degeneration and degree of inflammation can vary. The changes that occur in the context of steatosis hepatis can be visualized by means of imaging examinations (computer tomography, MRI, ultrasound).

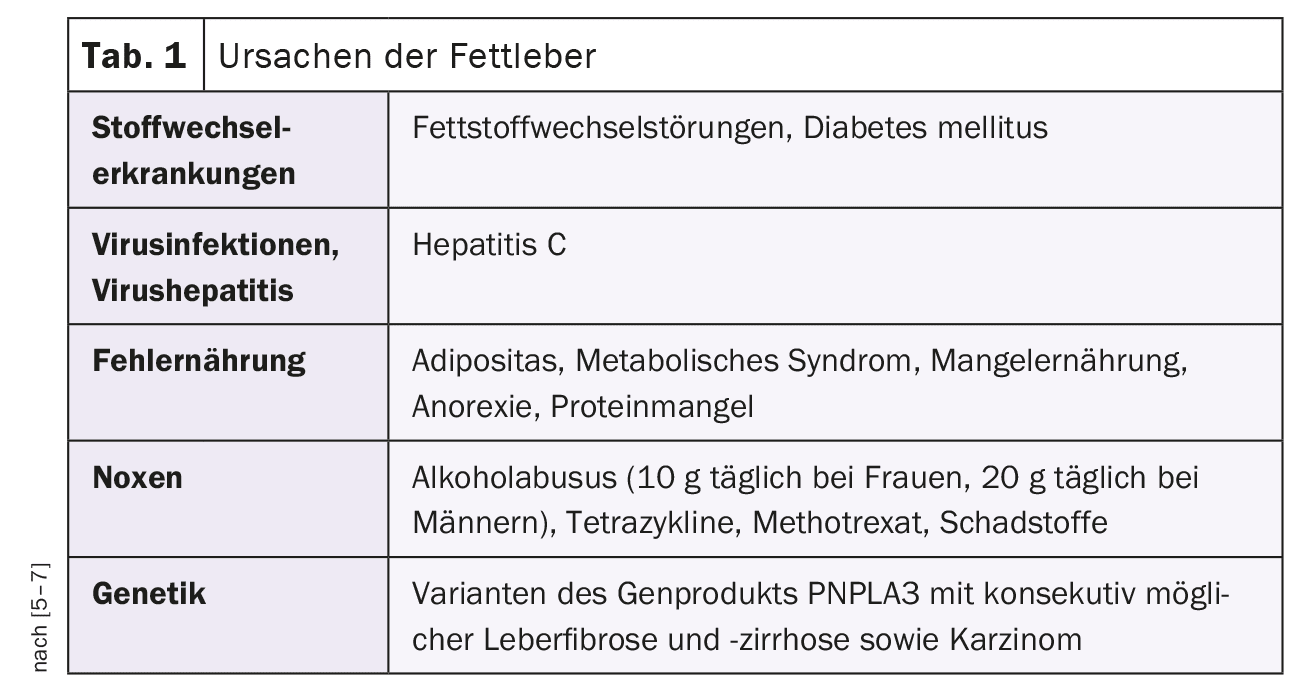

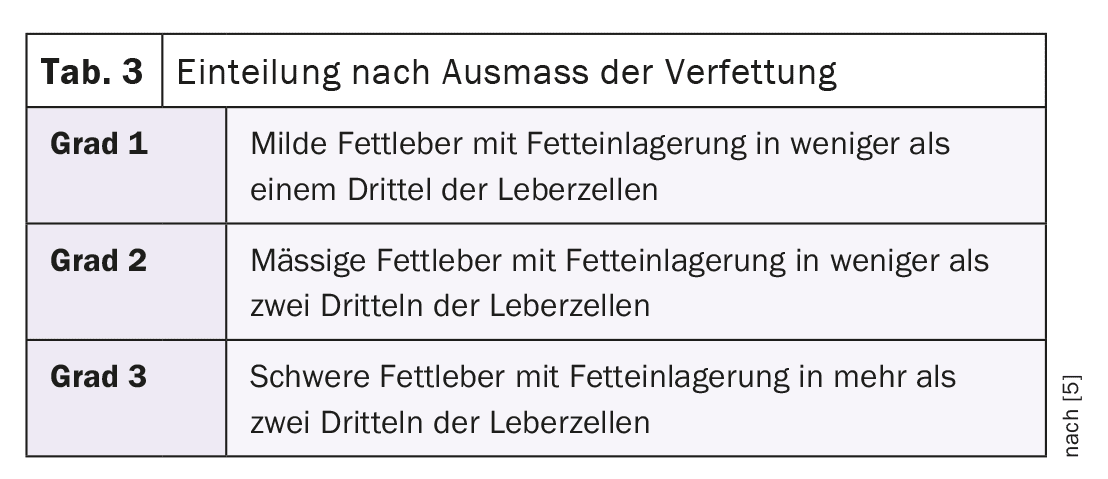

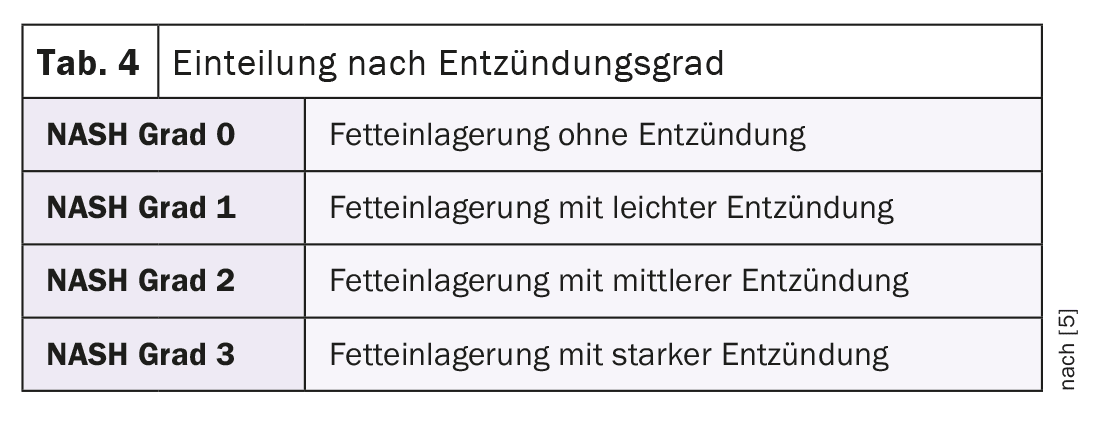

Steatosis hepatis, also known as fatty liver, is a pathological change in the organ with storage of triglycerides in the liver tissue [5–7]. Regardless of the cause of the increased fat storage in the liver, the term steatotic liver disease is used. Table 1 lists the various causes of hepatic steatosis, Table 2 the etiology. Tables 3 and 4 break down the extent of fatty degeneration and the degree of inflammation.

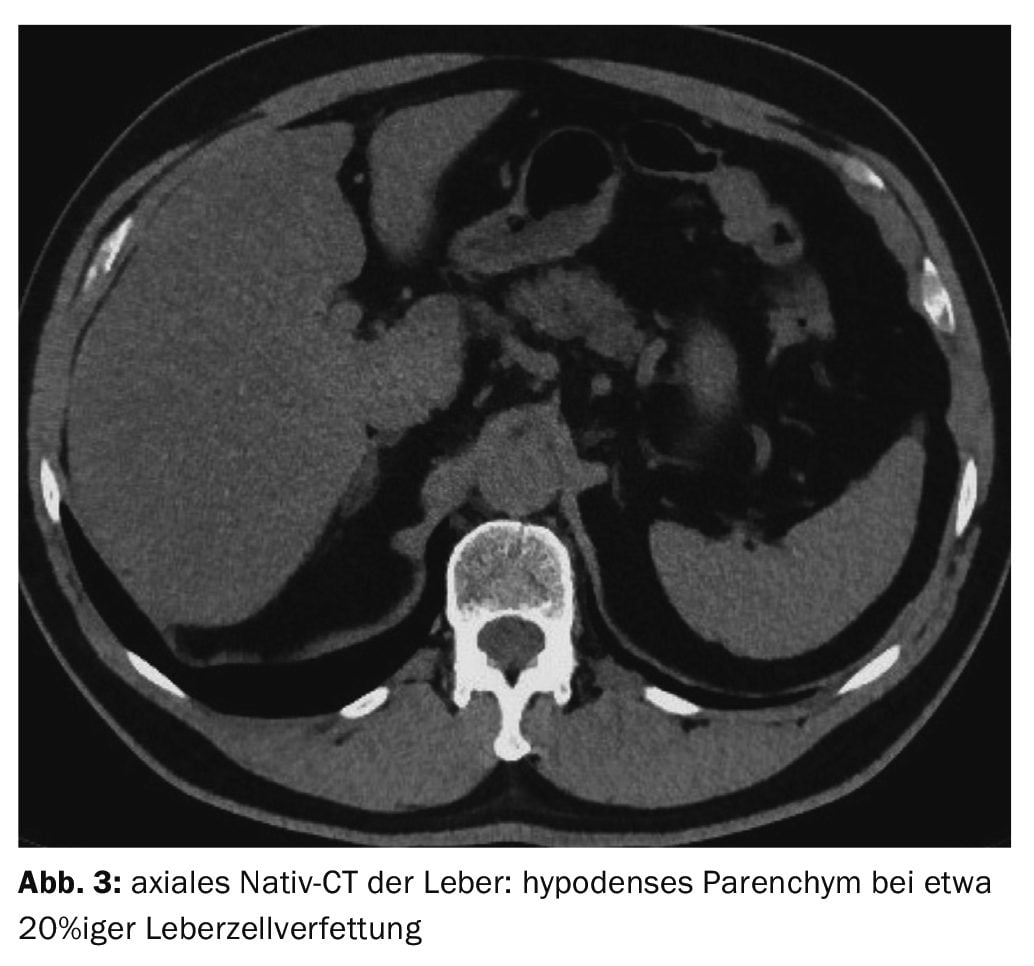

In addition to obesity, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and hyperlipoproteinemia, there may be other causes of NASH (Overview 1). Free radicals and cytokines also have an influence on the development of the disease [1]. The transition from a healthy liver to steatosis hepatis is fluid. If more than 50% of the hepatocytes are affected by fatty degeneration or the proportion of fat exceeds 10% of the total weight, a fatty liver is present. It is a common liver disease in industrialized countries, occurring in at least 20-30% of people. It usually causes no or uncharacteristic symptoms. These include a feeling of pressure or slight pain in the right upper abdomen, nausea, flatulence and loss of appetite.

The first step in the diagnosis is a medical history, physical and laboratory examination. Imaging procedures can confirm the suspicion of hepatic steatosis. If necessary, the diagnosis can also be confirmed by biopsy.

The treatment of fatty liver is aimed at treating the underlying disease that led to steatosis hepatis. If the triggering causes can be eliminated, the prognosis is good. By giving up alcohol and switching to a balanced, low-fat diet, the fatty liver can regress within 2 to 3 months. However, the disease can also lead to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in around 10 to 20% of cases.

The inflammatory form of fatty liver is steatohepatitis [3,4]. There is no infectious cause with pathogens. The non-specific symptoms of steatosis hepatis can include fever, jaundice and deterioration of the general condition. In contrast to simple fatty liver, gamma-GT, transaminases and leukocytes are elevated in the laboratory, as is C-reactive protein.

X-rays play no role in the diagnosis of fatty liver.

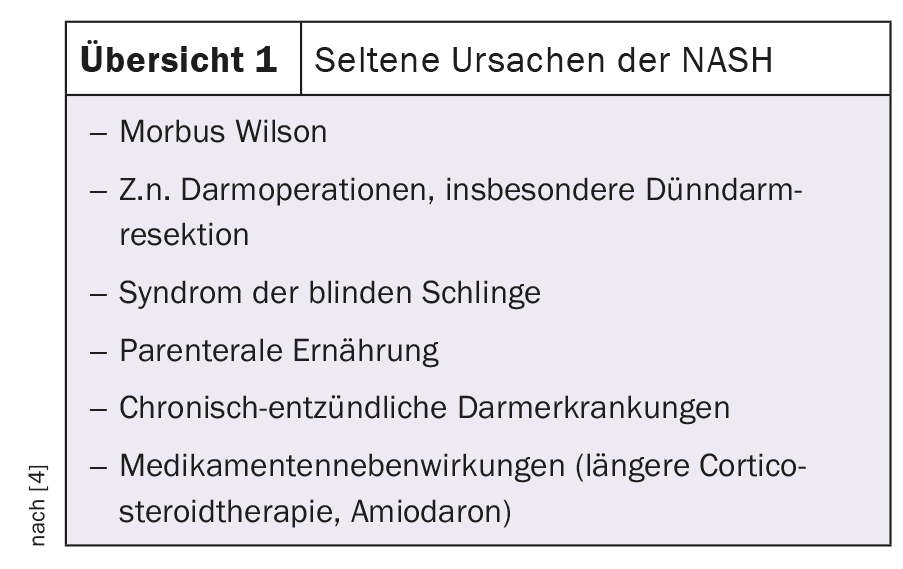

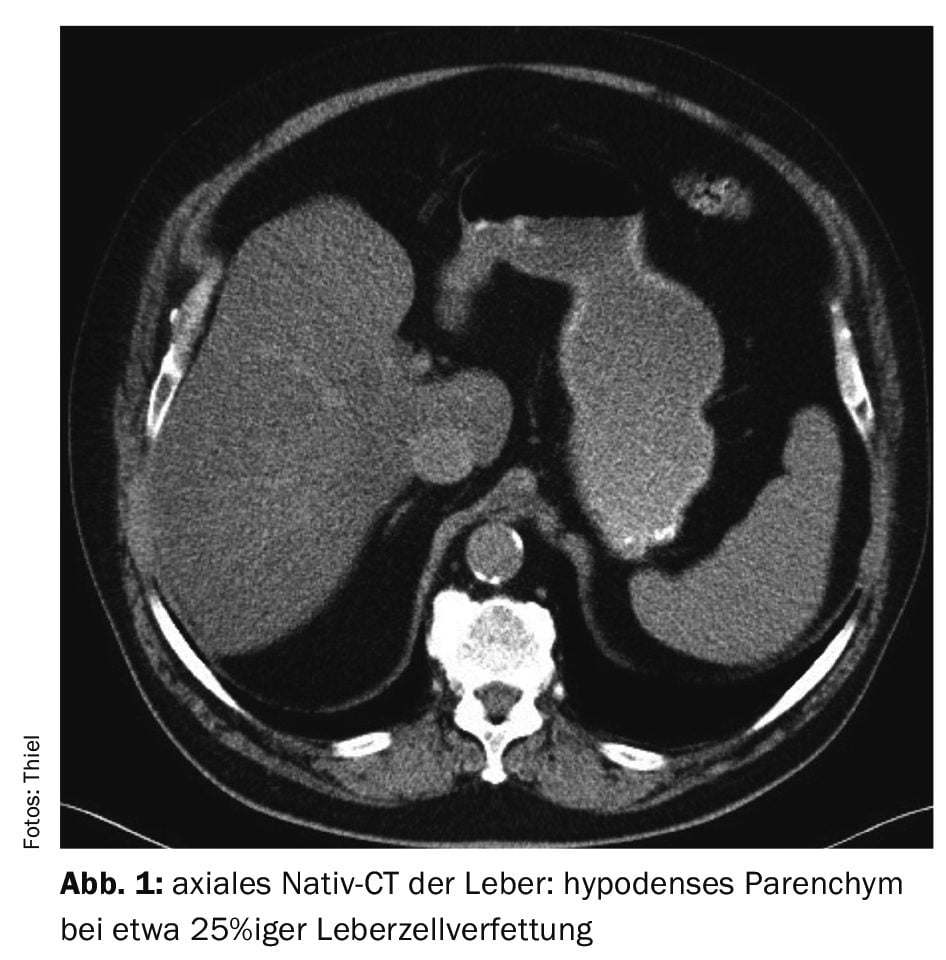

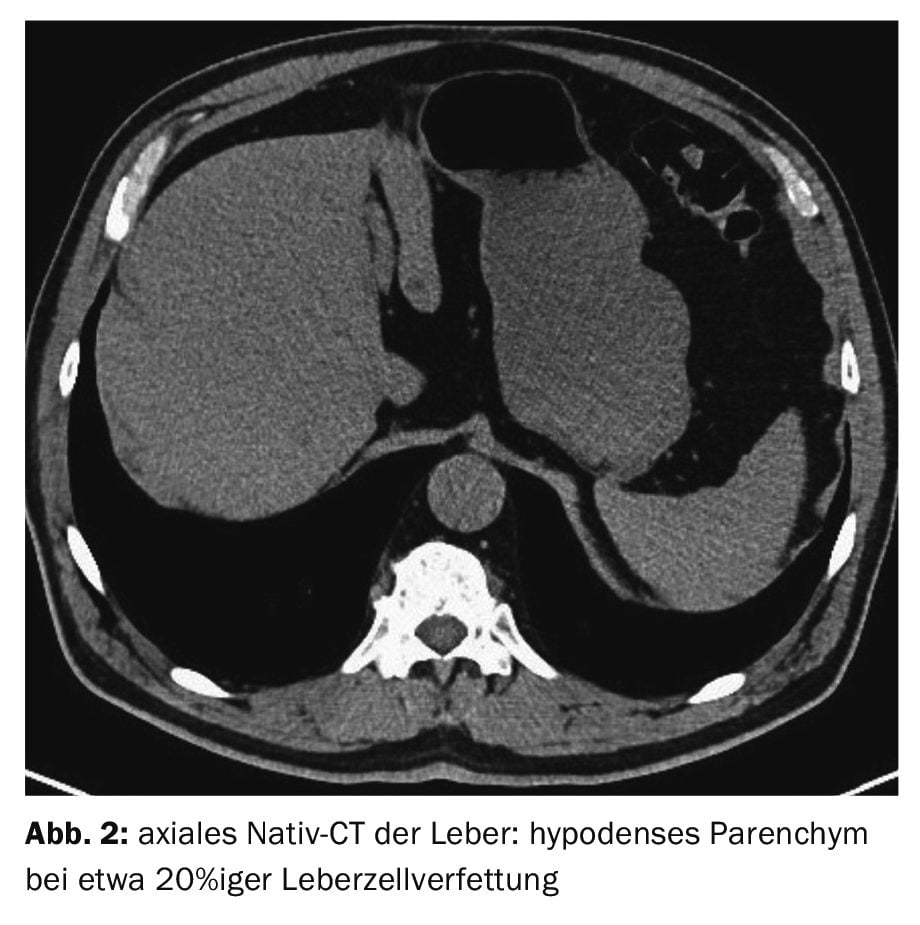

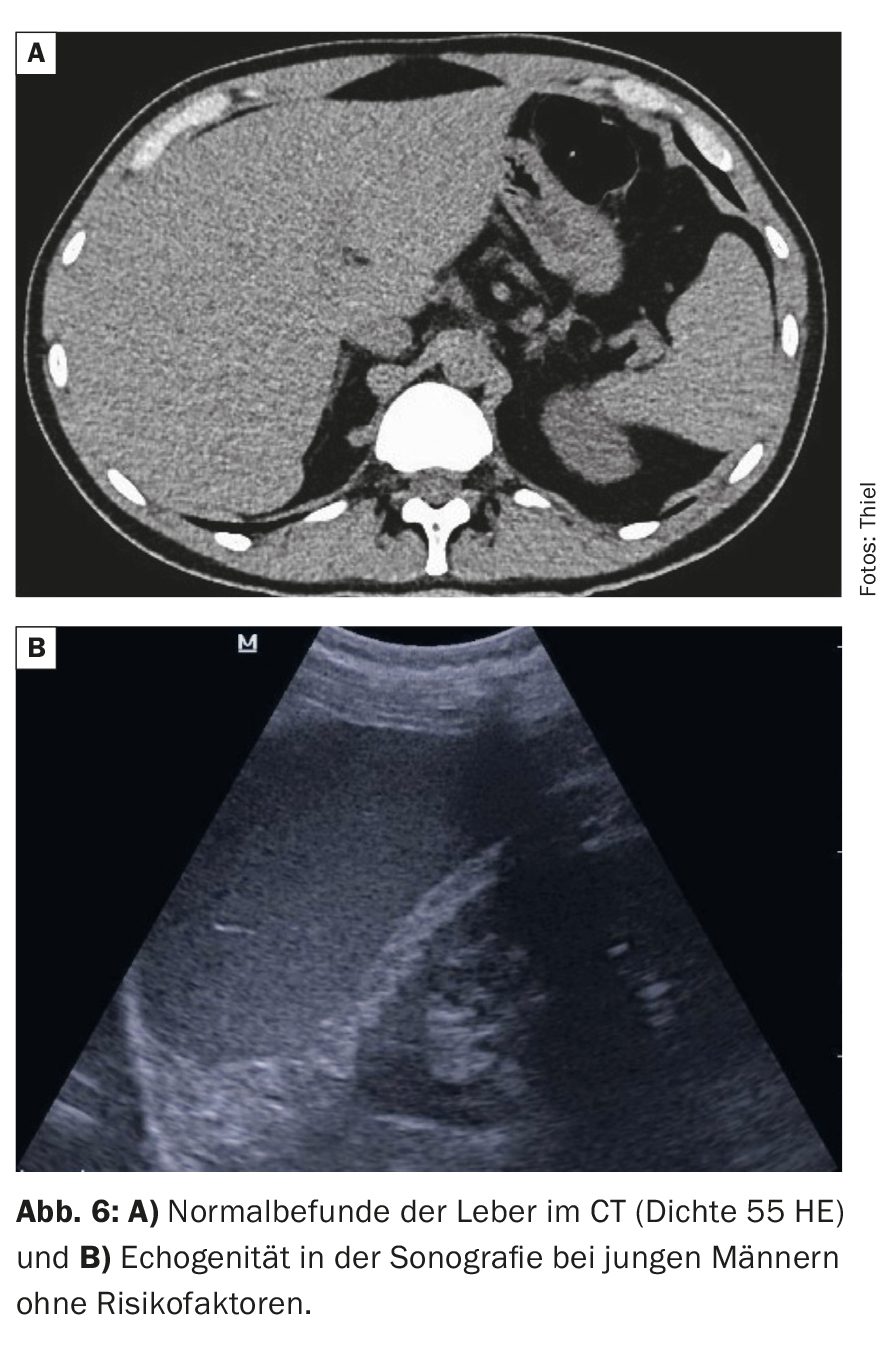

Computed tomography scans can precisely determine the size of the liver, the contour and the structure of the parenchyma. By measuring the density (in Hounsfield units, HE), the method is able to determine the degree of fatty degeneration of the liver cells with a high degree of accuracy. The normal liver shows native density values between 40 and 80 HE (Fig. 6A). A reduction in density of 10 U in steatosis corresponds to about 15% fatty degeneration of the liver cells [2]. Native computed tomography can therefore also quantify the success of therapy. In the case of pronounced fatty liver, the so-called contrast inversion may be visible in the native scans, i.e. the intrahepatic blood vessels appear hyperdense (lighter) than the hypodense (darker) fatty liver tissue. In healthy liver tissue, the ratios are reversed.

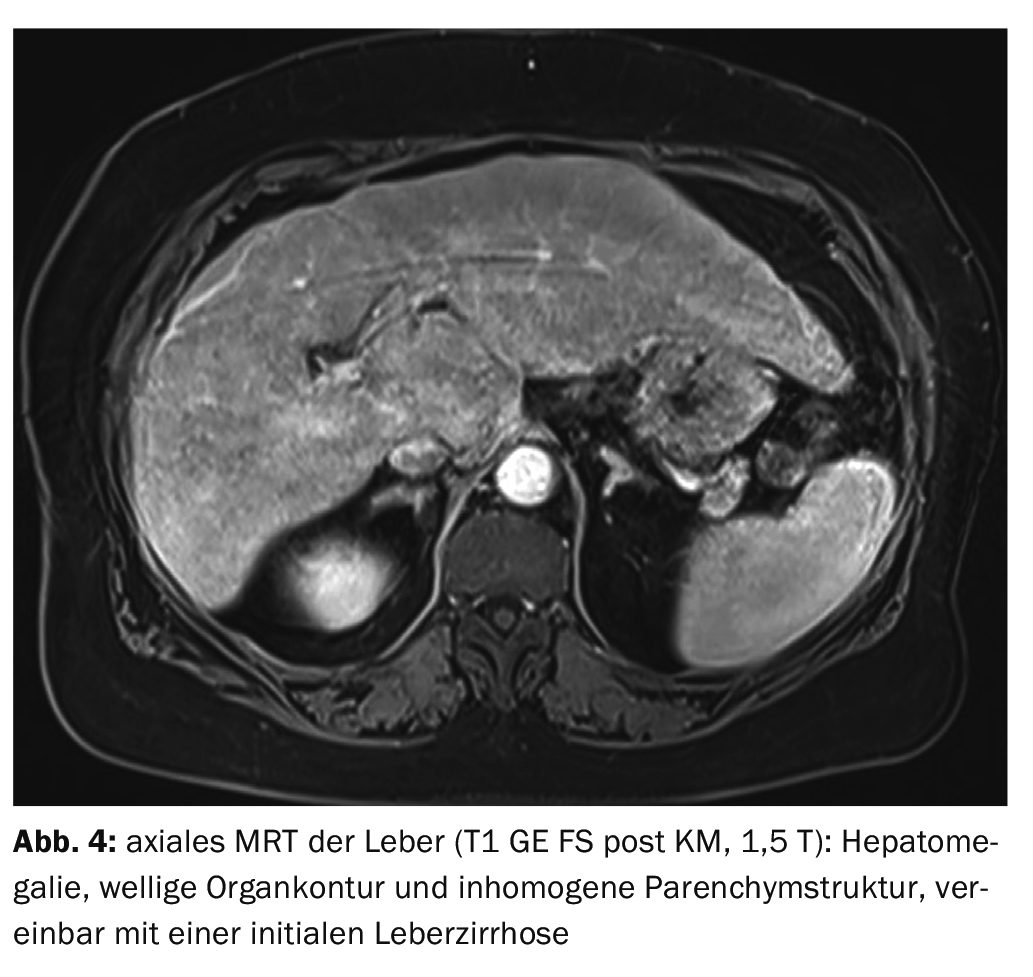

Magnetic resonance imaging can reliably verify structural changes in the liver. Contrast examinations, especially liver-specific ones, can make a valuable contribution. The possibility of quantifying the fat content of the liver tissue is less than in computer tomography.

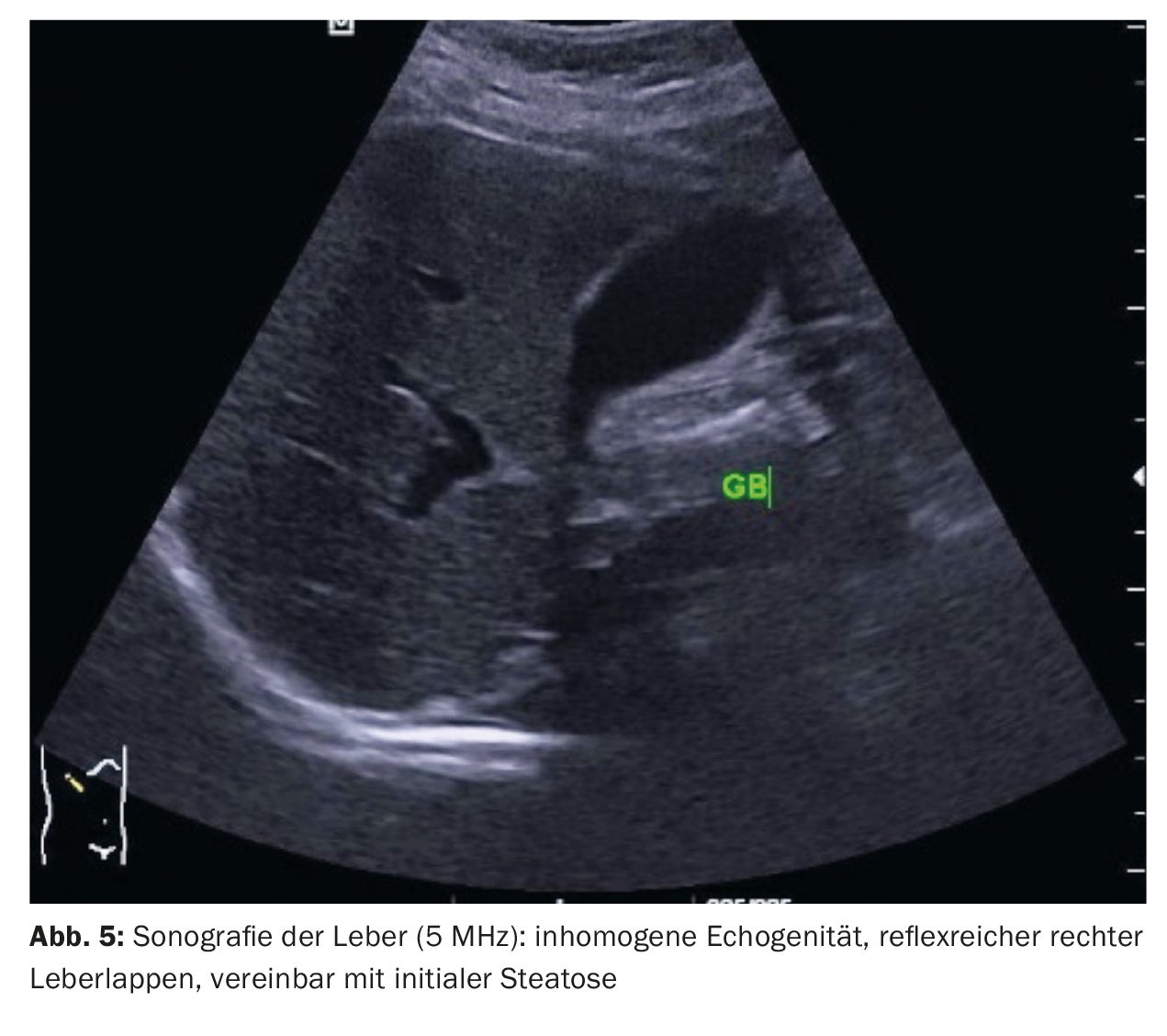

Sonography is very good at detecting the fatty liver [5,6]. This is hyperechoic compared to the neighboring kidney (Fig. 6B). Elastography can provide additional information.

Case studies

Case study 1 shows a pronounced fatty liver in a 79-year-old patient with a breast carcinoma on the left as part of the staging examinations. The native density values were 20 HE, corresponding to about 25% fatty liver cells (Fig. 1). No information on possible risk factors was available.

Case 2 demonstrates steatosis in a 66-year-old patient with a prostate adenoma, recurrent urinary tract infections and urinary bladder stones with liver density values of around 30 HE corresponding to approx. 20% fatty degeneration of the liver cells (Fig. 2).

Case 3 showed a 65-year-old patient with liver steatosis on a control CT scan due to nephrolithiasis (Fig. 3). Alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, other metabolic disorders or long-term drug therapy with possible liver parenchymal burden were not present. The measured liver density values of 35 HE indicated almost 20% fatty degeneration of the liver cells.

In case 4 , magnetic resonance imaging of the upper abdomen revealed initial liver cirrhosis on previous sonography, which had detected inhomogeneous steatosis and incipient parenchymal remodeling of the liver. There was hepatomegaly with a wavy contour of the organ and structural inhomogeneity, consistent with the onset of cirrhosis (Fig. 4) .

Case 5 shows a sonographic image of the upper abdomen of a 42-year-old female patient with recurrent complaints in the right upper abdomen. Cholecystolithiasis was detected, and a slight reflex increase was seen in the right lobe of the liver, consistent with an initial steatosis (Fig. 5).

Take-Home-Messages

- Fatty liver can have a variety of causes.

- There are no primary symptoms, but nausea, a feeling of pressure in the upper abdomen, flatulence and loss of appetite may occur as the disease progresses.

- Sonography and computer tomography are the imaging procedures used to detect steatosis hepatis.

- The prognosis is good if the triggering noxious substances such as alcohol, reduction of high-fat foods and lack of exercise are significantly reduced.

- If fatty degeneration of the liver cells persists, there is a 10-20% risk of developing liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Literature:

- Blechazc B, Stremmel W: NASH – nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Z Gastroeneterol 2003; 41(1): 77-90.

- Burgener FA, Herzog C, Meyers SP, Zaunbauer W: Differential diagnoses in computed tomography. 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York: 1997; pp. 730.

- Dendl LM, Schreyer AG. Steatohepatitis – a challenge? Radiologist 2012; 52(8): 745-752.

- Wikipedia: Steatohepatitis, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steatohepatitis, (last accessed 22.02.2024).

- DocCheck: Flexikon: Fatty liver, https://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Fettleber,(last accessed 22.02.2024)

- Leading Medicine Guide, www.leading-medicine-guide.com/de/erkrankungen,(last accessed 02/22/2024)

- Zimmermann HJ: Drug-induced liver disease. Drugs 1978; 16(1): 25-45.

GASTROENTEROLOGIE PRAXIS 2024; 2(2): 32–34