According to current understanding, atopic dermatitis is a T cell-mediated chronic inflammatory dermatosis, whereby the systemic inflammation may also affect extracutaneous body compartments. In addition to the comorbidity risks described as “atopic march” and an increased susceptibility to viral infections, there is evidence of associations with a whole range of other pathologies. Among other things, recent research findings indicate a possible correlation between atopic dermatitis and atherosclerosis.

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory immune-mediated skin disease that often persists for many years and belongs to the group of atopic diseases. According to the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), atopy is defined as “an individual or familial tendency to produce IgE antibodies in response to low concentrations of allergens (…) and to develop typical symptoms such as asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, or atopic dermatitis” [1,2]. The skin barrier disorders characteristic of atopic dermatitis, which are caused, among other things, by inadequate expression and secretion of the structural protein filaggrin, are thought to enable sensitization to aeroallergens in particular [2]. At the immunopathologic level, atopic dermatitis is characterized by Th2-dominated inflammation in the skin. In addition, however, elevated Th2-associated cytokines and chemokines are also found in the serum of atopic patients, and increased levels of eosinophil granulocytes have also been measured [3]. In summary, these findings suggest that atopic dermatitis can be assumed to involve systemic inflammation, which also favors the development of internistic comorbidities. Patrick Brunner, MD, Rockefeller University Hospital, New York (USA) gave a presentation on this relevant and timely area of research at the EADV Annual Meeting. In addition to Th2-mediated inflammatory processes underlying skin manifestations, other cytokine signaling pathways are involved in atopic dermatitis, the expert explained. These findings also inform the further development of modern systemic treatment strategies, the goals of which include reduction of skin manifestations as well as alleviation of comorbidities.

Risk factor for atherosclerosis?

Atopic dermatitis, like psoriasis, is a T-cell mediated inflammatory disease and it has been demonstrated that there are some similarities between these inflammatory dermatoses both at the tissue and cellular levels [4]. As with psoriasis vulgaris, the question is whether the systemic inflammatory processes are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and whether atopic dermatitis can be considered an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events. Inflammatory processes are known to play an important role in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis, and activation of endothelial cells has been shown to be a factor favoring this. In a recent study it was shown that psoriasis and atopic dermatitis have a higher incidence of atherosclerosis compared to skin-healthy controls [5]. Many other empirical studies report possible correlations between cardiovascular symptoms and atopic dermatitis [6,7].

Overall, however, the evidence is inconsistent and it is pointed out that methodological aspects of the study design must be considered when interpreting the data on internal medicine comorbidities in patients with atopic dermatitis, including the study population [2]. Among other things, differences have been noted between findings in the North American region and Europe, which may have to do with sociocultural aspects [8]. Regarding the pathophysiological mechanisms of a possible increased cardiovascular risk, the proinflammatory cytokines IL17 and IL22, which are also increased in psoriasis vulgaris, are discussed as drivers [2]. An analysis of the proteome* in the blood of 59 patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis revealed elevated atherosclerosis markers, including fractalkine/CX3CL1, CCL8, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), and “hepatocyte growth factor” (HGF), when compared with healthy subjects and with psoriasis patients, and these parameters correlated in part with the severity of atopic dermatitis [9].

* Proteome = totality of all proteins

What about other comorbidity risks?

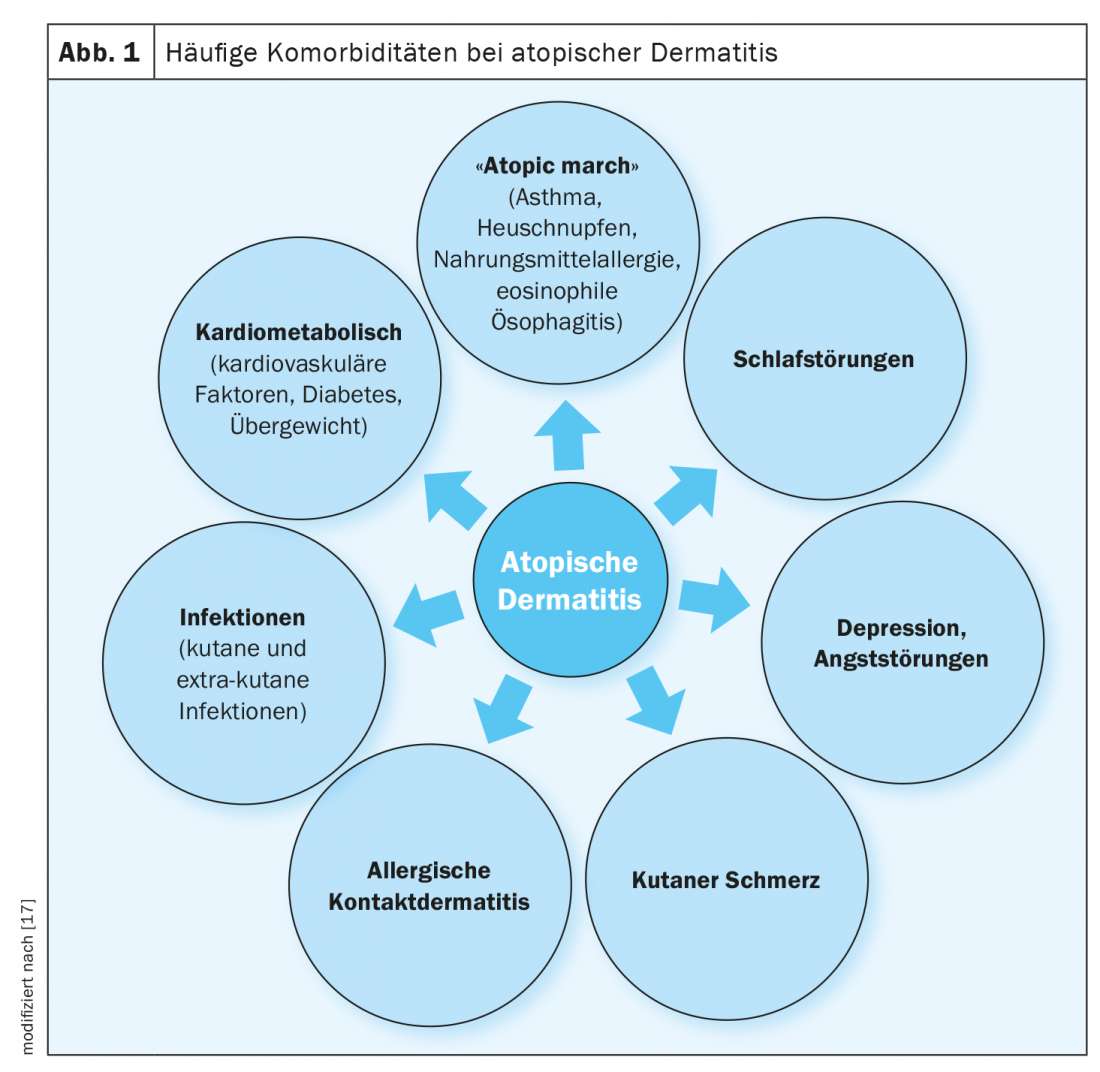

In addition to the comorbidities circumscribed as “atopic march” such as allergic bronchial asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and food allergy, and a possible increased cardiovascular risk, there are also findings of a clustered occurrence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes in patients with atopic dermatitis (Fig. 1) [8]. Furthermore, evidence was found for associations with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease [10]. And in a 2020 publication by Lowe et al. an increased risk of fracture is reported, Dr. Brunner said, although the cause-and-effect relationship is unclear [11,12]. It is empirically proven that patients with atopic dermatitis show a susceptibility to viral infections such as eczema hepaticum, eczema coxsackium or molluscum contagiosum, which may be related to a reduced occurrence of antimicrobial peptides – so to speak the skin’s own antibiotics [13]. With regard to malignancies such as lymphoma, only weak associations could be demonstrated, the speaker explained [11]. On the other hand, it is considered proven that neuropsychiatric disorders such as anxiety symptoms, depression, ADHD or autism spectrum disorders are more frequent in patients with atopic dermatitis, said the speaker [11].

Evidence-based associations are also available for comorbid sleep disorders. Epidemiological data show that insomnia is significantly more common in individuals with atopic dermatitis (OR 2.36; 95% CI 2.11-2.64) [14]. Similarly, postulated associations between atopic dermatitis and depression/anxiety disorders have not been dismissed out of hand, which can be inferred from several analyses of randomized-controlled trials-including Simpson et al. 2016 (n=380) and de Bruin-Welleret et al. 2018 (n=325) – in which treatment with dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis 16 weeks after baseline resulted not only in a reduction in pruritus and eczematous lesions, but was also associated with significant improvement in quality of life as well as anxiety symptoms and depressive disorders [15,16].

Source: EADV Annual Meeting 2020

Literature:

- Johansson SG, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113(5): 832-836.

- Traidl S, Werfel T: Atopic dermatitis and internal medicine comorbidities. The Internist 2019; 60: 792-798.

- de Graauw E, et al: Eosinophilia in dermatologic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2015; 35(3): 545-560.

- AAD Highlights 2018, www.aadhighlights2018.com

- Hjuler KF, et al: Am J Med 2015; 128 (12): 1325-1334.

- Silverberg JI, et al: Allergy 2015; 70(10): 1300-1308.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Krueger JG: Curr Opin Immunol 2017; 48: 68-73.

- Brunner et al: J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137(1) : 18-25.

- Brunner PM, et al: Sci Rep 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09207-z

- Kage P, Simon J-C, Treudler R: Atopic dermatitis and psychosocial comorbidity. JDDG 2020; 18(2): 93-102.

- Brunner PM: Inflammatory Disease: Atopic Dermatitis. Complications and Comorbidities. Patrick Brunner, MD, EADV Annual Meeting 2020 (Virtual) , Oct. 30, 2020.

- Lowe, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145(2): 563-571.e8

- Wang V, et al: Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020; S1081-1206(20)30558-5.

- Silverberg JI, et al: The Journal of investigative dermatology 2015; 135(1): 56-66.

- Simpson EL, et al: J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75(3): 506-515.

- de Bruin-Welleret M, et al: Br J Dermatol 2018; 178(5): 1083-1101.

- Silverberg JI: Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2019; 123(2): 144-151.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(1): 31-32 (published 2/21, ahead of print).