In patients with inadequately controlled asthma under maximum inhalation therapy, it should be critically questioned whether the diagnosis of asthma is really present and whether all treatment measures are being adequately implemented. If so, it is important to focus on the biologics available for the treatment of severe asthma. The determination of biomarkers can help to select the most suitable substance class in each case.

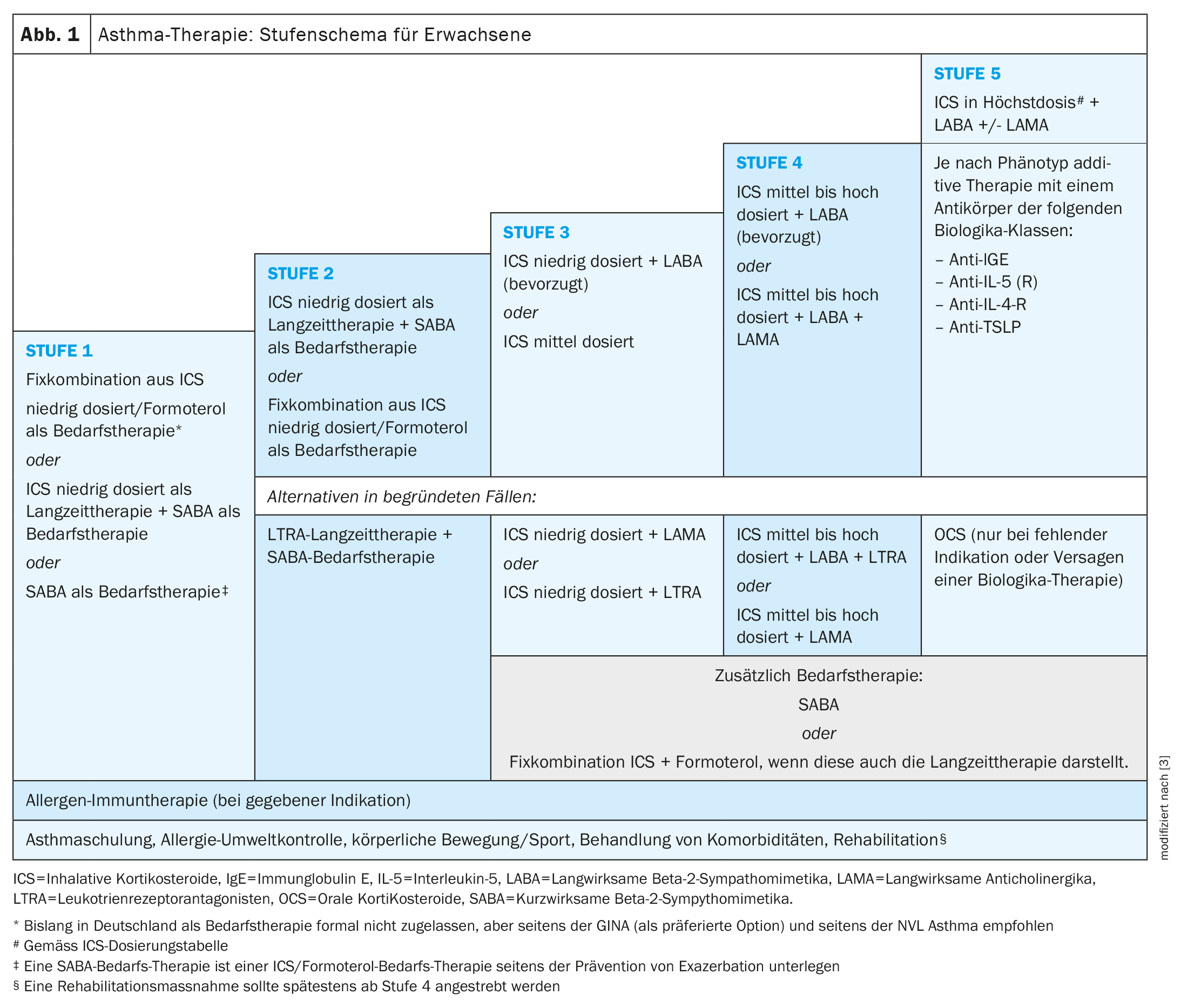

Asthma often occurs in childhood and adolescence, but can also manifest itself for the first time in adulthood [1]. “Adult-onset” asthma tends to be more severe and have higher exacerbation rates, reported Prof. Christophe von Garnier, MD, Chief Physician in the Department of Pneumology at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) [2–4]. “Adult-onset asthma is less frequently associated with allergies, but more frequently with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and other comorbidities. “Early-onset asthma usually corresponds to classic allergic asthma. Long-term and on-demand medications are used to control asthma symptoms according to the step-by-step scheme (Fig. 1). According to the new GINA** definition, asthma is considered severe if it proves to be refractory to maximum inhaled triple therapy (ICS in maximum dose and LABA plus possibly LAMA) [5]. If, for example, sufficient disease control is not achieved within a period of one month with maximum inhalation therapy, various clarifications should first be carried out:

- Is it really asthma or is it COPD instead, for example?

- Does the patient implement the proposed treatment measures?

- Is the correct inhalation technique being used?

- Are there avoidable asthma triggers (e.g. allergens)?

- Are there any untreated comorbidities?

If it is concluded that the asthma is really severe, the next step will be to test treatment with phenotype-specific biologics as an add-on therapy option [2,3]. The long-term goal is to achieve and maintain asthma remission, i.e. long-term, well-controlled asthma.

** Guidelines of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2022

Blood eosinophils and FeNO as biomarkers

The inflammatory processes underlying severe asthma are complex, heterogeneous and dynamic [6]. Atopic diathesis is the strongest predisposing factor to asthma development identified to date. However, in 30 – 50 % of adults with asthma, allergies to environmental allergens are not detectable either by history or by skin tests or determination of specific IgE in serum, which is why this form is also referred to as non-allergic or intrinsic asthma [3]. Allergic and non-allergic asthma are summarized in the literature under the generic term “type 2” asthma or “type 2-high” [7]. This is based on the finding that certain cytokines can be released not only by allergen-specific T helper cells (Th2 cells) of the adaptive immune system, but also by allergen-nonspecific ILC2 cells of the innate immune system, and lead to similar inflammatory patterns.

Type 2 biomarkers include blood eosinophils and FeNO [3,8,9]. In order to be able to narrow down the phenotype, the GINA recommendations recommend measuring these two biomarkers at least three times, as they are subject to strong individual fluctuations. For example, the number of blood eosinophils is influenced by the time of the last allergen contact and the time of year, and FeNO levels are influenced by infections or exposure to pollutants [3,10]. In addition, both biomarkers are significantly influenced by ICS and OCS therapies [3,11,12].

High eosinophilia leads to damage to the lung tissue, hyperresponsiveness and remodeling of the airways due to the activation of eosinophil cells [13]. The diagnosis of severe eosinophilic asthma requires at least two detections of more than 300 eosinophils/µl in the blood outside of exacerbations and without medication with systemic corticosteroids.

Biologics as add-on maintenance therapy

The active substances with interleukins (anti-IL-5-(R), anti-IL-4-R) or IgE as a target are aimed at the type 2 inflammatory pathway. Blood eosinophilia (≥300 cells/μl) is considered a predictor of response to monoclonal antibodies against IL-5 (mepolizumab, reslizumab) or against the IL-5-R (benralizumab) [20]. Blood eosinophilia (≥300 cells/μl) or an FeNO concentration >25 ppb are also predictors of a response to treatment with the anti-IL4R antibody dupilumab. Patients with severe allergic asthma and high IgE levels, on the other hand, are most likely to respond to omalizumab. If the IgE baseline value is below 76 I.U./ml, a clinical benefit of the anti-IgE antibody is less likely [19]. The monoclonal antibody tezepelumab, which will be approved in Switzerland in 2022, has a different mode of action to the substances mentioned above. The target of this biologic is TSLP (thymic stromal lymphopoietin). By binding to TSLP, tezepelumab prevents its interaction with the heterodimeric TSLP receptor. TSLP is a cytokine from the alarmin family that is mainly released by epithelial cells in response to various stimuli (e.g. viruses, allergens and pollutants), is involved in the inflammatory cascade in asthma and plays a role in the initiation and persistence of asthmatic airway inflammation [15]. In asthma, both allergic and non-allergic triggers induce TSLP production. Blocking TSLP with tezepelumab affects a broad spectrum of biomarkers and cytokines associated with inflammation (e.g. blood eosinophils, IgE, FeNO, IL-5 and IL-13) [15–17]. Accordingly, TSLP plays an important pathogenetic role in various subtypes of asthma [16,17]. A review article published in 2022 showed that tezepelumab is an adequate treatment option for severe uncontrolled asthma and <1500 eosinophils/μl regardless of FeNO and allergy status [18]. Furthermore, tezepelumab was shown to reduce the exacerbation rate in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma regardless of the eosinophil count at baseline.

Congress: Allergy & Immunology Update

Literature:

- Akar-Ghibril N, et al: Allergic Endotypes and Phenotypes of Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8(2): 429-440.

- “How to recognize and treat severe (Th2) asthma”, Prof. Dr. med. Christophe von Garnier, Allergy & Immunology Update, Grindelwald, 27.01.2024.

- Lommatzsch M, et al: S2k guideline for the specialist diagnosis and treatment of asthma 2023, German Society for Pneumology and Respiratory Medicine e.V. (ed.), https://register.awmf.org,(last accessed 07.03.2024)

- Baan EJ, et al: Characterization of Asthma by Age of Onset: A Multi-Database Cohort Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 1825-1834.e1828.

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), 2022, www.ginasthma.com,(last accessed 07.03.2024)

- Busse WW: Biological treatments for severe asthma: A major advance in asthma care. Allergol Int 2019; 68(2): 158-166.

- Hinks TSC, Levine SJ, Brusselle GG: Treatment options in type-2 low asthma. Eur Respir J 2021; 57(1).

- Hammad H, Lambrecht BN: The basic immunology of asthma. Cell 2021; 184: 1469-1485.

- Lommatzsch M: Immune Modulation in Asthma: Current Concepts and Future Strategies. Respiration 2020; 99: 566-576.

- Chipps BE, et al: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Stability of Blood Eosinophil Levels. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18: 1978-1987.

- Lommatzsch M, et al: Impact of an increase in the inhaled corticosteroid dose on blood eosinophils in asthma. Thorax 2019; 74: 417-418.

- Jackson DJ, et al: Characterization of patients with severe asthma in the UK Severe Asthma Registry in the biologic era. Thorax 2021; 76: 220-227.

- Patterson MF, Borish L, Kennedy JL: The past, present, and future of monoclonal antibodies to IL-5 and eosinophilic asthma: a review. J Asthma Allergy 2015; 8: 125-134.

- Berry M, et al: Pathological features and inhaled corticosteroid response of eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic asthma. Thorax 2007; 62: 1043-1049.

- Swiss Drug Compendium,

https://compendium.ch,(last accessed 07.03.2024) - Menzies-Gow A, Wechsler ME, Brightling CE: Unmet need in severe, uncontrolled asthma: can anti-TSLP therapy with tezepelumab provide a valuable new treatment option? Respiratory research 2020; 21(1): 268.

- Gauvreau GM, et al: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: its role and potential as a therapeutic target in asthma. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2020; 24(8): 777-792.

- Brusselle GG, Koppelman GH: Biologic Therapies for Severe Asthma. The New England journal of medicine 2022; 386(2): 157-171.

- Omalizumab, https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2022/20221014157073/anx_157073_de.pdf,(last accessed 07.03.2024)

- Mepolizumab, reslizumab and benralizumab, www.leitlinien.de/themen/asthma/4-auflage/kapitel-4,(last accessed 07.03.2024).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(3): 26-28 (published on 20.3.24, ahead of print)