Levodopa remains the most effective and well-tolerated medication for Parkinson’s disease. However, half of the patients experience fluctuations in efficacy (wearing-off, dyskinesias) after only a few years. Effective countermeasures are a shortening of the intake intervals, the addition of COMT or MAO-B inhibitors or dopamine agonists. When drug strategies no longer achieve satisfactory cessation, device-assisted treatments are increasingly used earlier (deep brain stimulation and infusion treatment). Neurorehabilitation is also important at all stages of the disease. Specific treatment protocols have been developed using randomized controlled trials and are well effective. Developments in rehabilitation research show that web-based training (e.g., with tablets) or the use of electronic aids (e.g., wearable sensors to overcome freezing) are gaining importance.

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by asymmetric bradykinesia, resting tremor, and rigor. The cause of these motor symptoms is a dopamine deficiency in the basal ganglia, which results from the loss of projecting neurons from the midbrain (substance nigra). Good response to dopaminergic therapy is an important supportive criterion for diagnosis. This article focuses on the treatment of motor symptoms. The important non-motor problems are mentioned but not discussed in depth.

Basics of drug treatment in the early stage

Motor Parkinson’s symptoms leading to diagnosis occur when 50-80% of dopamine-containing cells have already perished. In discussing treatment, it is important to keep in mind the progression of Parkinson’s disease into three stages:

- Early phase (2-5 years) when oral therapy is uncomplicated. Patients are well adjusted with few doses daily (“honeymoon” phase).

- Middle phase (up to 10 years) in which motor complications such as fluctuations in effect and dyskinesias occur. After 4-6 years already about 40%, at the end of the middle phase 90% of the patients are affected [1].

- Late phase (>10 years) in which axial-motor (postural instability, dysarthria) and cognitive problems dominate.

- In the early phase, the question is when to start treatment. The decisive criterion is the impairment in everyday life. The start of treatment should not be delayed unnecessarily, for example to prevent subsequent fluctuations in effect. This is because it is not the duration of pharmacological treatment but the duration of the disease that is decisive for the risk of fluctuations in efficacy. Moreover, in the early phase, the results of oral pharmacotherapy are best. Delaying treatment longer would shorten this uncomplicated phase of treatment without relevantly affecting the risk for motor complications. On the other hand, to treat before debilitating symptoms occur is also not justified, as no neuroprotective effect of medication has been demonstrated so far.

Initiation with levodopa, dopamine agonists, or MAO-B inhibitors.

Treatment can be started with levodopa, dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine as patches), or, for mild symptoms, an MAO-B inhibitor (selegiline, rasagiline), with levodopa remaining the most effective and well-tolerated medication more than 50 years after its introduction [2]. Levodopa, as a precursor substance, can cross the blood-brain barrier and is converted into dopamine by dopamine-containing nerve cells. Levodopa is always combined with a decarboxylase inhibitor (benserazide or carbidopa) to improve bioavailability and tolerability. Dopamine agonists mediate their effects via dopamine receptors. MAO-B inhibitors act dopaminergically by inhibiting dopamine breakdown.

Combining levodopa from the outset with a COMT inhibitor (entacapone) that prolongs the duration of levodopa action is not indicated, as shown in the STRIDE-PD trial [3]. The concept that this combination with more continuous dopaminergic stimulation would reduce the risk of dyskinesia was not confirmed. On the contrary, entacapone increases the frequency of dyskinesia after about 2.5 years and therefore represents a risk factor.

Levodopa is the therapy of choice, especially in elderly patients. When patients are younger, treatment initiation with dopamine agonists is recommended because fluctuations in effect are less common than with levodopa. However, dopamine agonists are less effective and have more side effects. In younger patients, pay particular attention to impulse control disorders such as Internet addiction and hypersexuality. If treatment with dopamine agonists is insufficient, levodopa should be added or a switch to this medication should be considered [4]. The risk of motor complications can be reduced by trying to keep the levodopa dose below 400 mg [5]. If foot dystonia is present early, control with levodopa may be difficult. Even when non-motor problems (namely depression) dominate, dopamine agonists have an advantage over levodopa.

Basics of advanced stage drug strategies.

After a few years, most patients are dependent on levodopa. Although well effective, motor complications are the main problem in advanced disease (after 10 years in 90% of patients). Wearing-off fluctuation is explained pathophysiologically by the degeneration of dopamine-containing nigrostriatal neurons, which lose their buffering function and thus the ability to balance plasma fluctuations of levodopa. The effect of levodopa becomes dependent on its pharmacokinetics. Dyskinesias are probably due to supersensitivity of dopamine receptors caused by chronic dopamine deficiency. Therefore, the most important reason for motor complications is disease duration, not treatment duration. For example, a comparative clinical trial demonstrated that wearing-off fluctuations occurred after an average of almost six years of disease duration, regardless of whether levodopa had been used for several years (Italian cohort) or only delayed for a few months (sub-Saharan cohort) [6]. Other risk factors for motor complications include young age at onset, daily levodopa dose, and female gender [5].

There are a number of drug strategies to minimize Wearing-Off fluctuations and dyskinesias. Parkinson’s protocols, completed by the patient or a caregiver (e.g., trained nurse), are an important tool. They show the temporal relationship of medication-taking times with periods of off states or dyskinesias. With this information, levodopa intake intervals can be selectively shortened in the presence of wearing-off fluctuations, and dyskinesias can be mitigated by dose reduction. In addition to stronger fractionation, combinations with COMT and MAO-B inhibitors, which prolong the effect of levodopa, are an option. Attention should be paid to the increase in dyskinesias, as these cannot always be controlled by dose reduction of levodopa. The addition of dopamine agonists incl. Amantadine, which also has antidyskinetic effects, is another common strategy.

New developments: Safinamide (Xadago®) and IPX066 (Numient®)

Among the new developments, the selective and reversible MAO-B inhibitor safinamide and the L-dopa retard drug IPX066 will be presented here.

Safinamide has both dopaminergic (MAO-B inhibition) and non-dopaminergic effects (inhibition of stimulated glutamate release). The latter could have an antidyskinetic effect. Safinamide significantly prolonged on-time (approximately 1 hr) without increasing bothersome dyskinesias in mid- to late-stage Parkinson’s disease in a randomized controlled trial [7]. Dosages were 50 and 100 mg. Due to the long half-life (20-30 hrs), once-daily dosing is sufficient. The mean age of the patients was 60, all were on levodopa treatment. Side effects and discontinuation rates were not different from placebo. The primary endpoint of reducing dyskinesia was not met. However, post-hoc analysis showed that in patients who were more severely affected, at least for the higher dosage of 100 mg there is an antidyskinetic effect.

Safinamide (Xadago®) was approved in Switzerland late last year as an add-on therapy to levodopa. Whether safinamide is also tolerable in older (>75 years) and more vulnerable patients (e.g., with dementia) will be assessed in an ongoing non-interventional observational study.

Although levodopa (combined with decarboxylase inhibitors) is the most effective treatment, motor complications are a relevant problem after only a few years because of the short half-life of 1.5 hours. The motor response becomes shorter and less predictable as it progresses. In the 1990s, sustained-release preparations were developed (Sinemet® CR and Madopar® DR), but these did not prove successful with regard to motor complications. On the contrary, the absorption and motor effects of sustained-release preparations are even more unreliable. Retard preparations can even promote dyskinesia if they accumulate in the stomach and are then released in excess (often in the afternoon).

Therefore, a new levodopa preparation has been developed, IPX066, whose capsules combine the rapid component with a sustained release. EU approval was granted at the end of last year under the brand name Numient®. The approval is based on three phase III studies [8]. In the APEX-PD trial, which included early-stage Parkinson’s disease patients, IPX066 significantly improved ADL function compared to placebo at all doses (145, 245, and 390 mg, three times daily) (UPDRS II), the motor symptoms (UPDRS III) and quality of life (PDQ39). In patients with advanced PD and effect fluctuations, IPX066 prolongs on-time without disruptive dyskinesias by an average of one hour compared with standard drug (ADVANCE-PD, Parallel Design) and by 1.4 hours compared with the combination of levodopa and entacapone (ASCEND-PD, Cross Over Design).

Apparatus-assisted treatments for motor complications.

Despite adjustment of oral medication, motor complications become difficult to control during the course. When satisfactory cessation is no longer possible, device-assisted treatments such as deep brain stimulation (THS) and infusion treatments with duodopa or apomorphine should be evaluated early. An improvement in quality of life was demonstrated for THS and Duodopa compared with best available oral therapy. Therefore, these therapies are discussed in more detail here.

Deep brain stimulation

Since its introduction in the 1980s, more than 100,000 patients have been treated with THS worldwide. THS is a stereotactic procedure in which basal ganglia nuclei (primarily the subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus) are inhibited by electrical pulses. The inserted electrodes are connected to batteries via subcutaneous cables, which are usually inserted in the subclavicular region. The surgical risk is low (about 1% for infections and bleeding).

Crucial to the success of THS is good patient selection. An important prerequisite is that the patient responds well to levodopa, which is predictive of the effect of THS. Thus, younger patients benefit particularly well, whereas patients with axial motor (postural instability) or cognitive problems are not suitable. The Earlystim study demonstrated that earlier THS (i.e., after 7.5 years on average instead of after more than 10 years as in previous studies) not only significantly reduced effect fluctuations but also substantially improved quality of life by approximately 25% compared with best oral therapy [9]. It is also interesting to note that the patients with the poorest baseline quality of life benefit the most [10]. The result of the Earlystim study is also noteworthy because drug treatment can usually still be adjusted well in earlier stages of the disease. Therefore, in younger patients (<60 years), evaluation of THS is recommended as early as three years after the onset of motor complications. However, the basic prerequisite for the indication of THS remains that motor complications cannot be satisfactorily adjusted with oral therapy, i.e., are refractory to therapy.

Infusion treatment with Duodopa

If the conditions for THS are unfavorable, infusion treatment with Duodopa is a good alternative. Duodopa was introduced in Scandinavia in the early 1990s. That infusion treatment with levodopa leads to an improvement in effect fluctuations via more stable plasma levels was known early on. However, this treatment required nonpractical intravenous doses of up to two liters per day because of the poor solubility of levodopa.

The key innovation of Duodopa is that levodopa can be 20 times more concentrated in gel form. In addition, it can be continuously applied directly to the site of absorption (proximal jejunum) via a PEG tube. In a well-controlled study (double dummy design), a significant improvement in motor complications and quality of life was already demonstrated in a small population of patients (n = 66) [11]. In addition to continuous administration via a pump, the effect of infusion treatment with Duodopa is also based on bypassing the gastric passage. Irregular gastric emptying is partly responsible for variations in effect during oral therapy.

Duodopa is appropriate for patients with advanced disease who are elderly and already have some cognitive deficits and postural instability with risk of falls. As with THS, the oral setting should be refractory to therapy. Periprocedural complications are relatively common (e.g., wound problems or pain at the stoma) but are usually passive and benign [11]. In rare cases (about 2%), peritonitis may occur. Therefore, it is important that Duodopa treatment be administered by an experienced interdisciplinary team of neurologists and gastroenterologists.

A common side effect of Duodopa is polyneuropathy. A recently published prospective study measuring nerve conduction velocities showed that the incidence of symptomatic polyneuropathies was nearly 20% over a two-year observation period [12]. Pathophysiologically, levodopa-induced vitamin deficiency is suspected (folic acid, vitamin B6/B12 deficiency) because of the association with elevated metabolites (homocysteine), so these vitamins should be determined. Monitoring with neurographs is also useful. It is recommended to substitute folic acid and vitamin B12 in case of lowered values. Whether preventive treatment is also indicated has not been clarified [13]. Polyneuropathies rarely force discontinuation of therapy unless they occur with similar acute onset as in Guillain-Barré syndrome. In addition, interdisciplinary teamwork with the Parkinson’s nurse is critical to the success of Duodopa treatment. She instructs the patients and their relatives in handling the pump. This also prevents technical problems such as probe dislocations or blockages.

Principles and goals of neurorehabilitation

In the course of the disease, people with Parkinson’s disease are increasingly confronted with limitations in mobility, balance, posture, gait and fine motor skills, which make it more difficult to cope with everyday life. The disruption of daily activities (e.g., dressing, preparing a meal, etc.) also reduces quality of life. In particular, axial and fine motor problems are poorly responsive to pharmacological therapies and are the focus of neurorehabilitation [14].

Physiotherapy plays an essential role in all stages of the disease. One of the main goals is to learn movement strategies that allow people to manage everyday life more easily. Well-controlled studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of physiotherapy. This also led to the development of standardized guidelines [15]. It is quite possible that physiotherapy also has a beneficial effect on the disease process. For example, it has recently been shown that light physical activity (6 hrs per week, e.g. walking to work, housekeeping, etc.) can reduce the risk of developing PD by more than 40% [16].

Amplitude training

A central motor problem in Parkinson’s disease is impaired amplitude regulation. The stride length is shortened and thus mainly responsible for the slowing down during walking. The step cadence itself is normal or may even be increased. A new concept was developed for therapy, Lee Silverman Voice Therapy BIG (LSVT BIG). This is a standardized amplitude training with 16 therapy units over four weeks [17,18]. According to the latest guideline of the German Society of Neurology, the treatment is recommended for Parkinson’s disease. In LSVT BIG therapy, people with Parkinson’s learn to specifically increase the amplitude of movement (e.g., step length) and thus improve movement deceleration. It is a high-dose therapy that is particularly effective for patients in the earlier stages of the disease. The exact dosage of physiotherapy must be adjusted individually. A recently published, large, randomized-controlled trial examined dosing that was too low (4 units over 8 weeks), which is not effective in the early stages of the disease [19].

Exercise programs for home

The goal of neurorehabilitation is also to counsel the affected person and their family on how to maintain an active lifestyle. This includes home exercise programs that target balance, muscle strength, joint mobility, aerobic performance (e.g., jogging, hiking, fast walking), and fine motor skills. It has been shown that people with Parkinson’s disease can significantly improve their motor performance if they follow a daily exercise program at home in addition to individual therapy. To encourage this self-training, group therapies are very appropriate (six-week blocks of two sessions per week), which also provide instruction for individual home training [20]. In later stages of the disease, it is important to prevent inactivity, which is often associated with fear of falling, with training of aerobic power, muscle strength and joint mobility. Prevention of cardiovascular morbidity, which is increased in PD because of immobility, is also a focus.

Cueing strategies to overcome freezing.

A central problem in Parkinson’s is the disruption of automatic movements. For example, walking, which is automated in healthy people, often has to be performed purposefully by people with Parkinson’s disease. Thus, an automatic movement such as walking requires an additional cognitive attentional effort. This is tiring in everyday life. When this cognitive control decreases in the course of the disease, so-called freezing increasingly occurs, which are short-term motor blockades, typically during walking. Freezing occurs especially when the affected person changes the motor program (get up and go) or performs several movements at the same time (walk and respond to address). Tight spaces (door, elevator) are also common triggers. In neurorehabilitation, sufferers are taught cueing strategies to help overcome freezing. The principle is to make movements purposeful by using acoustic stimuli (loud counting, metronome, music) (Fig. 1A), visual stimuli (lines on the floor (Fig. 1B) or somatosensory stimuli (rhythmic stimuli through touch) [14].

Physiotherapy in early and late stages

In the early phase, it is recommended to perform outpatient physiotherapy rather in blocks (e.g. over a month) and more intensively (3 to 4 times a week). This is possible with a prescription for 2×9 sessions. Within this block, the patient learns various balance, strengthening and stretching exercises, which also includes strategy training (with or without cueing). He can continue these exercises as home training to maintain everyday functions. If symptoms worsen, e.g. after six months, the block of 18 sessions can be repeated.

In the later stages of the disease, prevention of falls and cardiopulmonary morbidity is often the primary focus. Therefore, a physiotherapeutic permanent treatment with one to two sessions per week is useful. With increasing disability and fluctuations in effect, inpatient stays (2-3 weeks) are often necessary with multidisciplinary programs specifically tailored to patients with PD. The goal is to maintain independence at home as much as possible or reduce the need for care with individually adapted walking and balance training as well as everyday life training. The inpatient setting allows for targeted medication adjustments in the event of effect fluctuations using exercise protocols.

Occupational Therapy

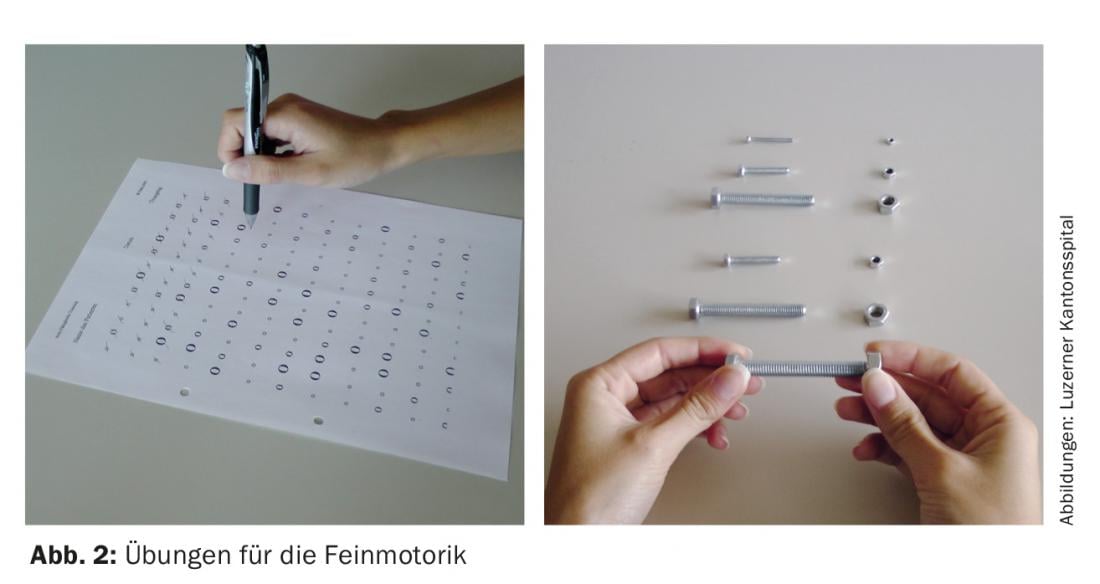

In occupational therapy, the focus is on the targeted relearning and re-learning of various everyday activities. For example, fine motor difficulties in everyday life are analyzed and treated. Using a standardized evaluation, specific fine motor exercises are instructed that can later be performed at home (Fig. 2).

Occupational therapy also clarifies exactly which strategies are useful in order to better manage everyday life. Various aids are used, such as a bath board, which makes it easier to get in and out of the bath, or adapted cutlery to cut meat better. Domicile-oriented occupational therapy plays an important role, allowing optimal adaptation of measures to the home situation. People with Parkinson’s disease receive advice on which strategies they can use to better achieve their goals in everyday life, e.g. breaking down complex actions into individual steps, time pressure management, using so-called “cues” (stimuli), etc. In a randomized controlled trial, it was shown that once-weekly, domicile-oriented occupational therapy over ten weeks leads to a significant improvement in everyday function. [21].

Speech therapy is also important. Proven effective, LSVT LOUD therapy aims to improve voice with high-dose intensive practice [22]. Speaking is trained on different levels by means of a hierarchy of exercises up to free conversation. The focus is on improving comprehensibility. This is mainly achieved by a greater volume when speaking (“think loud/shout”). What is learned is gradually transferred to everyday speaking situations.

Neurorehabilitative research

The development of standardized tests and therapy programs for finger dexterity is one of our research priorities. In a recently completed randomized-controlled trial, we demonstrated that standardized dexterity training delivered at home over four weeks improved fine motor skills relevant to everyday life [23]. However, there was no sustained effect of the intervention over twelve weeks (therapy break). This means that people with Parkinson’s should be encouraged to continue exercising even after completing the intensive four-week therapy block.

The use of communication technologies such as tablets or wearable sensors will play an increasingly important role. Affected persons can solve various motor and/or also cognitive tasks by means of web-based applications (apps). The supervising therapist can provide feedback online and progressively adjust the tasks in difficulty. At our Parkinson’s center, we are currently testing the usability of a dexterity app (Fig. 3) . Another application of technical aids could be sensors worn on the ankles. These sensors could detect freezing episodes early and then trigger a cue (auditory, sensory) to help the patient overcome freezing. Patients would become more independent and less reliant on the help of a third party.

The use of non-invasive brain stimulation (repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, rTMS), may be another therapeutic option of the future. A recently published meta-analysis showed that rTMS has a positive effect on bradykinesis [24]. In our Parkinson’s center, we are investigating whether the method is also effective for treating fine motor deficits.

Literature:

- Ahlskog JE, Muenter MD: Frequency of levodopa-related dyskinesias and motor fluctuations as estimated from the cumulative literature. Mov Disord 2001; 16(3): 448-458.

- Gray R, et al: Long-term effectiveness of dopamine agonists and monoamine oxidase B inhibitors compared with levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson’s disease (PD MED): a large, open-label, pragmatic randomised trial. Lancet 2014; 384(9949): 1196-1205.

- Stocchi F, et al: Initiating levodopa/carbidopa therapy with and without entacapone in early Parkinson disease: the STRIDE-PD study. Ann Neurol 2010; 68: 18-27.

- Waldvogel D, et al: 2014 recommendations for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Working Group of the Therapy Commission of the Swiss Neurol. Society. Swiss Arch. of Neurology and Psychiatry 2014; 165(5): 147-151.

- Olanow CW, et al: Factors predictive of the development of levodopa-induced dyskinesia and wearing-off in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2013; 28(8): 1064-1071.

- Cilia R, et al: The modern pre-levodopa era of Parkinson’s disease: insights into motor complications from sub-Saharan Africa. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 10): 2731-2742.

- Borgohain R, et al: Two-year, randomized, controlled study of safinamide as add-on to levodopa in mid to late Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2014; 29(10): 1273-1280.

- Dhall R, Kreitzman DL: Advances in levodopa therapy for Parkinson disease: review of RYTARY (carbidopa and levodopa) clinical efficacy and safety. Neurology 2016 Apr 5; 86(14 Suppl 1): S13-24.

- Schüpbach WM, et al: Neurostimulation for Parkinson’s disease with early motor complications. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(7): 610-622.

- Schüpbach WM, et al: Predictors of outcome of STN-DBS in Parkinson’s disease with early motor complications. Late-breaking abstract, MDS Meeting, 2016, Berlin.

- Olanow CW, et al: Continuous intrajejunal infusion of levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, double-dummy study. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13(2): 141-149.

- Merola A, et al: Peripheral neuropathy associated with levodopa-carbidopa intestinal infusion: a long-term prospective assessment. Eur J Neurol 2016 Mar; 23(3): 501-509.

- Uncini A, et al: Polyneuropathy associated with duodenal infusion of levodopa in Parkinson’smdisease: features, pathogenesis and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(5): 490-495.

- Vanbellingen T: Physiotherapeutic approaches in Parkinson’s disease. Practice Physical Therapy 2010; 3: 198-202.

- Keus M, et al: European Physiotherapy Guideline for Parkinson’s Disease, KNGF/ParkinsonNet, The Netherlands, 2014. large, open-label, pragmatic randomised trial. Lancet 2014; 384(9949): 1196-1205.

- Yang F, et al: Physical activity and risk of Parkinson’s disease in the Swedish National March Cohort. Brain 2015; 138(Pt 2): 269-275.

- Ebersbach G, et al: Comparing exercise in Parkinson’s disease – the Berlin LSVT®BIG study. Mov Disord 2010; 25(12): 1902-1908.

- Janssens J, et al: Application of LSVT BIG intervention to address gait, balance, bed mobility, and dexterity in people with Parkinson disease: a case series. Phys Ther 2014; 94(7): 1014-1023.

- Clarke CE, et al: Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy vs No Therapy in Mild to Moderate Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 2016 Mar; 73(3): 291-299.

- Tickle-Degnen L, et al: Self-management rehabilitation and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord 2010; 25(2): 194-204.

- Sturkenboom IH, et al: Efficacy of occupational therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13(6): 557-566.

- Fox C, et al: LSVT LOUD and LSVT BIG: Behavioral Treatment Programs for Speech and Body Movement in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsons Dis 2012; 2012: 391946.

- Vanbellingen T, et al: in preparation.

- Chou YH, et al: Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor symptoms in Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72(4): 432-440.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(5): 18-25.