An effective treatment regimen in PD is closely linked to a personalized approach. Depending on the age of onset and subtype of the disease, the challenges are different. In addition to the control of non-motor symptoms, the focus is on the therapy of motor symptoms. Especially in the long-term, combinations can achieve effective control.

Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPS) is a systemic disorder that can cause multiple symptoms in numerous organs. Predominantly, these are non-motor in nature. These include psychological complaints such as depression, apathy, or anxiety disorders, olfactory dysfunction, visual disturbances, gastrointestinal symptoms, sleep disturbances, or autonomic cardiovascular symptoms. Accordingly, IPS patients show pathological results in quantitative olfactory tests in 80-100%, as Prof. Dr. med. Claudia Trenkwalder, Kassel (D), pointed out. Approximately 51% of those affected have anosmia, 35% have severe olfactory dysfunction, and 14% have moderate olfactory dysfunction. Gastrointestinal complaints such as motility disorders can be attributed to various causes. For example, hyper-permeability of the intestinal wall, alpha-synuclein deposition in the myenteric plexus, or changes in the composition of the microbiome. In addition, 80% of all affected individuals develop clinically relevant dysphagia during the course of the disease. This is associated with a significant reduction in quality of life, difficulty taking medication, and malnutrition. Underlying this is a multifactorial genesis involving dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic pathways of the central swallowing network as well as peripheral neuromuscular influences. Speech therapy, optimization of dopaminergic medication, and intensive expiratory muscle strength training can help, she said.

Motor symptoms in view

Motor symptoms of IPS include bradykinesia, rigor, and tremor. They are also the ones who determine the diagnosis. In order to initiate effective therapy management, it is crucial to detect the respective subtype and its course, emphasized Prof. Lars Timmermann, MD, Giessen, Germany. This is because the clinical course of tremor-dominant Parkinson’s, for example, is much slower than other forms. In the early phase of the disease, the therapies usually work very well. However, as the disease progresses, motor complications increase and gait disturbances or dysarthria may occur. The late phase is then characterized by increasing need for care and often dementia.

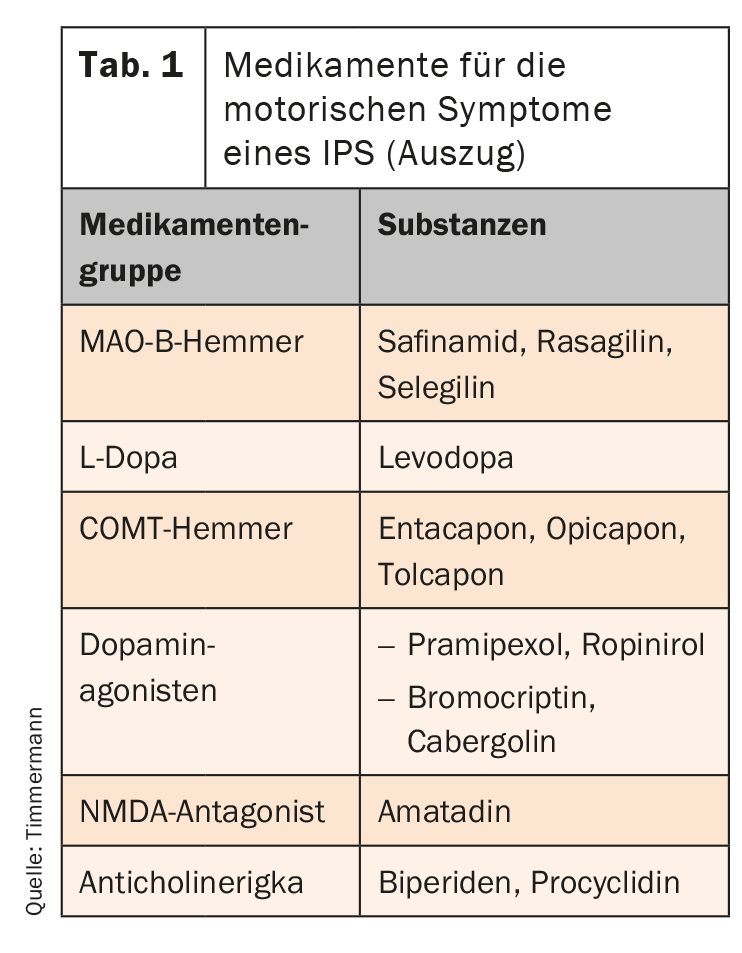

The pharmacological portfolio has been significantly expanded in recent years. Six drug groups are now available (tab. 1). First and foremost, L-dopa – also combined with a decarboxylase inhibitor – is used. It is converted to dopamine in the CNS and is thus available as a transmitter. However, fluctuations in effect occur during long-term use. They initially manifest as end-of-dose deterioration, but can extend to unplannable “off” conditions. An MAO-B inhibitor, for example, can then be used as an add-on therapy. By selectively inhibiting MAO-B, they increase the concentration of dopamine and are very well tolerated. Safinamide has a dual mechanism of action. Selective, reversible inhibition of monoamine oxidase (MAO)-B and simultaneous regulation of glutamate release, which is increased in PD, can achieve balanced and long-lasting control of motor symptoms.

Avoid escalations

When pharmacological interventions are no longer effective in particularly severe cases, therapy can be escalated with continuous stimulating procedures. Currently, the most thoroughly studied is deep brain stimulation. It can significantly improve poor mobility condition, fluctuations and dyskinesias. Jejunal L-dopa pump infusion can improve fluctuations, and subcutaneous administration of apomorphine via a pump system is effective primarily for fluctuations but not for dyskinesias.

Source: DGN 2020

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021, 19(1): 21 (published 2/3/21, ahead of print).