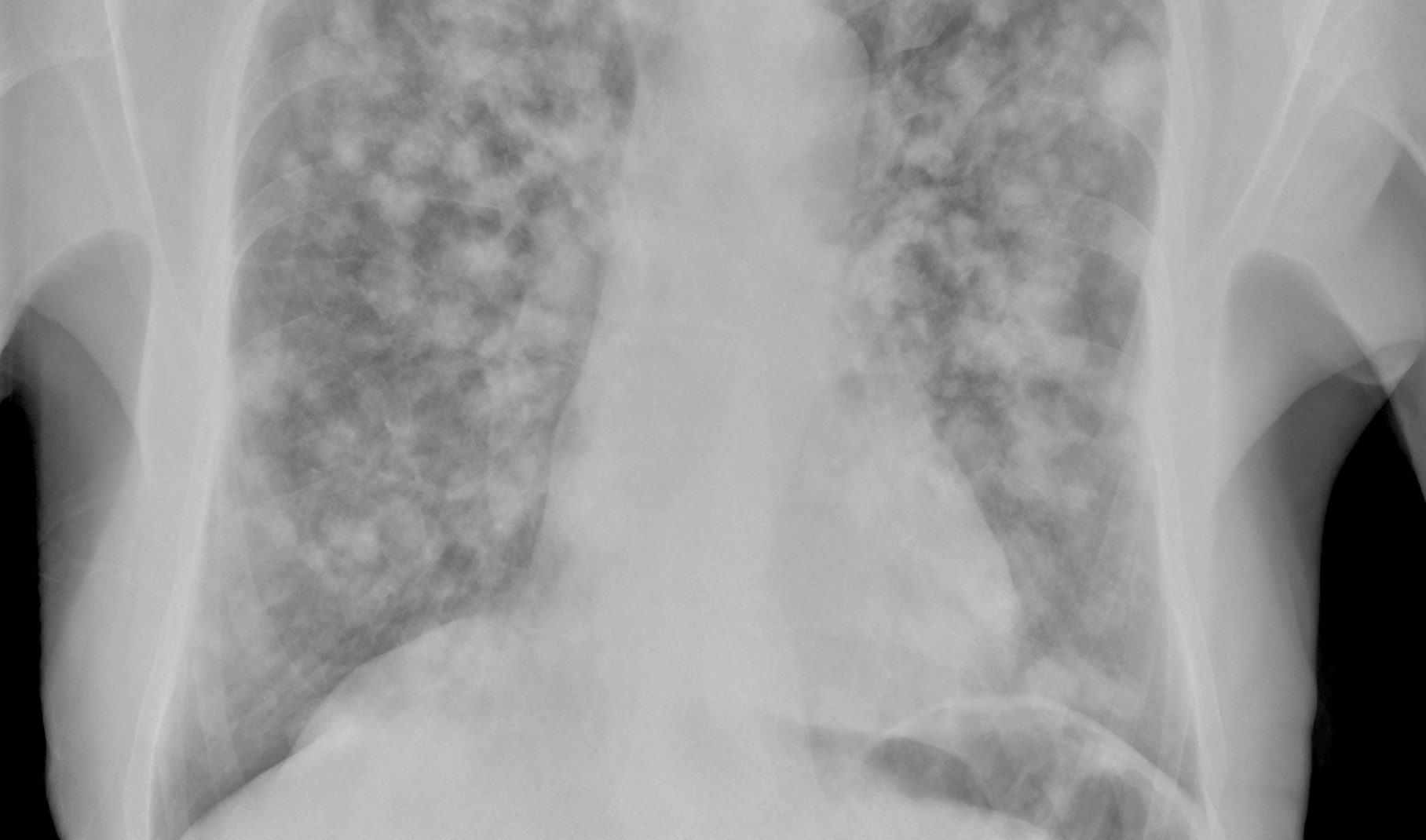

Asthma is a heterogeneous, multifactorial, chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, which is usually characterized by bronchial hyperresponsiveness and/or variable airway obstruction and can manifest itself clinically through respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath, chest tightness, wheezing, coughing) of varying intensity and frequency. The pathophysiology of asthma is very complex and therapy has changed fundamentally in recent decades. In this article, we discuss the importance of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and a paradigm shift in therapy.

Asthma is a heterogeneous, multifactorial, chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that is usually characterized by bronchial hyperresponsiveness and/or variable airway obstruction and can manifest clinically as respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath, chest tightness, wheezing, coughing) of varying intensity and frequency [1]. The pathophysiology of asthma is very complex and therapy has changed fundamentally in recent decades. In this article, we discuss the role of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and a paradigm shift in therapy.

Development of asthma therapy

Systemic corticosteroids were discovered around 1950 due to their effectiveness in the treatment of asthma. At around the same time, inhaled beta-2 agonists were also introduced for the symptomatic relief of the disease. However, due to the side effects associated with systemic corticosteroids, asthma therapy was initially mainly carried out with beta-2 sympathomimetics. However, it soon became apparent that inhaled beta-2 agonist therapy was associated with increased mortality when used alone. During this time, systemically acting sympathomimetics such as oral ephedrine, intravenous adrenaline or inhaled adrenaline, anticholinergics such as inhaled scopolamine and methylxanthines such as caffeine or theophylline were also used to treat acute and life-threatening airway obstructions. These therapies were not yet aimed at the pathomechanisms of asthma, which were still largely unknown at the time, and had no long-term therapeutic benefit. Around 1970, the first inhaled corticosteroid (beclomethasone) was developed, which was initially used alone and later in combination with inhaled beta-2 agonists for the treatment of asthma [2].

At that time, bronchoconstriction was at the center of pathophysiological concepts; the relevance of chronic inflammation was only increasingly understood in the following years. For this reason, early therapies were aimed at alleviating symptoms and there was no concept for long-term anti-inflammatory therapy of the disease. As the understanding of asthma has progressed, therapies have evolved and medications have been categorized into controllers and relievers, corresponding to disease control and symptomatic therapy. The controllers include above all the ICS, which revolutionized asthma therapy and still form the basis of anti-inflammatory asthma therapy today. They are used either alone or preferably in combination with long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABA). The controllers also include leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs), although these are less effective than ICSs in the vast majority of patients. They therefore play a subordinate role in modern asthma therapy due to possible relevant side effects [1].

With an increasingly better understanding of the inflammatory pathomechanisms of asthma, monoclonal antibodies that can be administered subcutaneously or intravenously have been developed in the last two decades for patients with severe asthma that is uncontrolled despite inhaled therapy having been exhausted. These biologics target specific inflammatory pathways and are used in patients for whom standard therapy is not sufficient. The current guidelines call for the use of biologics before systemic application of glucocorticosteroids. The latter may only be used in long-term therapy if biologics are ineffective. With the development of biologics, complete disease remission has become a realistic therapeutic goal for many patients with severe asthma. Biologics in particular can also be very effective against common comorbidities associated with asthma, such as chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, chronic urticaria and atopic dermatitis. Furthermore, in patients with a relevant IgE-mediated allergy, allergen immunotherapy (AIT), which is applied either sublingually or subcutaneously, is a supportive option for reducing this pathomechanism and improving disease control [2]. The goals of asthma remission are the permanent absence of asthma symptoms, the permanent avoidance of asthma exacerbations, stable lung function tests and no need for systemic corticosteroids to treat asthma [2].

This opens up the possibility of individually tailored treatment for asthma. However, the basis remains the inhaled application of ICS in varying doses for almost all patients across all degrees of severity and therapy stages. In view of the broad spectrum of ICS molecules, different dosages, different combination partners, different application concepts (maintenance therapy and/or on-demand therapy) and different devices, there are a large number of variables whose clinical significance is often unclear. This overview will therefore attempt to present clinically relevant aspects of the use of ICS and their combination partners.

ICS and beta-2 sympathomimetics

As early as the beginning of the 2000s, it was shown that even low doses of ICS significantly reduce mortality in asthma [3]. In contrast, studies have shown that monotherapy and/or abuse of short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA) were associated with an increased risk of exacerbations and increased mortality [4,5]. This was later also observed for long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABA) in monotherapy [6]. After the first LABA/ICS combination came onto the market in the mid-1980s, studies comparing the efficacy and safety of ICS/LABA combination therapy with stand-alone ICS or LABA therapy followed in the 1990s and beyond. In a key study, the FACET study, it was shown that a combination of low-dose budesonide with formoterol (LABA/ICS) is superior to a higher ICS dose in terms of lung function, but that a higher ICS dose has advantages in the prevention of exacerbations [7]. Later, however, the “Goal Study” in over 3400 patients with mild to moderate asthma also showed that despite combination therapy with LABA and ICS at high doses, a relevant proportion of patients did not achieve complete disease control in a one-year observation period [8]. There was therefore a clinical need for additional treatment options and/or treatment concepts. This led, among other things, to the development of the concept of “Single Inhaler Maintenance and Relief Therapy ([S]MART)” for the treatment of asthma. This therapy concept is also referred to as MART (Maintenance and Relief Therapy) for short, as the “S” in SMART originally stood for the trade name of the formoterol/budesonide fixed combination with which the first large studies were conducted. After the results were confirmed in further studies with other ICS, the “S” now stood for “Single Inhaler”. In everyday clinical practice, SMART and MART are used synonymously.

Single Inhaler Maintenance and Reliever Therapy ([S]MART)

This therapy concept involves long-term therapy (maintenance) with 2× daily application of an ICS/formoterol combination in one device. Of the LABA, only formoterol is suitable for this purpose, as it has both a long duration of action and a rapid onset of action, so-called “fast-acting and long-acting beta-2 agonists”. If necessary, i.e. symptom-oriented, the patients also inhale the same ICS/LABA combination as a reliever. This therapy concept is based on the fact that bronchial inflammation increases a few days before a clinical exacerbation and an early increase in anti-inflammatory ICS therapy can prevent or at least mitigate this exacerbation. (S)MART therapy thus makes it possible to adapt the intensity of the anti-inflammatory ICS therapy to the course of the disease against the background of a basic anti-inflammatory treatment. Several large studies have demonstrated the superiority of (S)MART therapy over conventional application regimens. A relevant reduction in both the total number of exacerbations and the number of severe exacerbations was demonstrated [9].

(S)MART therapy was originally developed for patients with moderate to severe asthma in treatment stages III-V and is also recommended in these treatment stages in current national and international guidelines. There is overwhelming evidence of the benefits of this therapy in these treatment stages.

Anti-Inflammatory Reliever Therapy (AIR)

For many years, a purely symptom-oriented inhaled application of a SABA was recommended for the inhalation therapy of patients with mild asthma (stage 1). However, it is known that beta-2 sympathomimetic monotherapy can worsen disease control and increase exacerbation rates and mortality [4]. Severe exacerbations can also occur with mild asthma. It therefore seemed plausible to test a purely demand-oriented inhaled therapy with an ICS-formoterol combination in patients with mild asthma in analogy to the (S)MART concept. This therapy concept is known as AIR therapy (anti-inflammatory reliever) . Here too, formoterol must be used as a LABA due to its rapid and long-lasting effectiveness. A SABA/ICS combination (salbutamol/beclomethasone) in an inhaler was investigated in a study [10], but this combination is not yet approved in the EU and Switzerland.

Several large studies have shown that AIR therapy is superior in all relevant endpoints to on-demand SABA monotherapy in stage I, but also in stage II compared to the previously common ICS continuous therapy with SABA on demand. The first studies to show this were the SYGMA studies [11]. Therefore, AIR therapy is recommended in national and international guidelines for patients in treatment levels 1 and 2 [1,12]. Despite the high level of evidence for AIR therapy for mild asthma and the clear guideline recommendations, the combination products available for this therapy have not yet been approved in the EU and Switzerland, which poses a dilemma for prescribing physicians.

The importance of the two variable ICS/formoterol therapy concepts (AIR and [S]MART), which are based on the course of the disease and the intensity of bronchial inflammation, in the current staged treatment regimen for asthma in adults is shown in Figure 1 . Depending on the severity and course of the disease, it may make sense to switch between the two treatment modalities in the sense of escalation or de-escalation (Fig. 2). Although the combination therapy of ICS/LABA is now established as the standard, further questions arise:

- Is (S)MART suitable for every asthma patient?

After adequate information, it will be possible to treat the majority of patients appropriately in this way. However, it remains an individual decision that must be discussed with the patient in the sense of shared decision making. If patients have achieved good disease control with another guideline-based therapy, there is no reason to change this. There are also patients who prefer a rigid therapy regimen and many patients feel the need to have another medication, usually an SABA, available in addition to their continuous inhalation therapy as a further option for “emergencies”, which provides an additional sense of security. - Is every ICS/LABA combination suitable for (S)MART? As already mentioned, this therapy requires a LABA with a rapid onset of action and long-lasting efficacy. This is the case with formoterol. For this reason, the step-by-step scheme (Fig. 1) only includes formoterol as a LABA for on-demand application with an ICS. With regard to the ICS combination partner, budesonide was used in almost all (S)MART studies. One study used beclomethasone with similar efficacy.

- Can (S)MART be prescribed with ICS/formoterol as an on-demand therapy and an alternative ICS-LABA as a maintenance therapy? In patients receiving maintenance therapy with ICS/LABA combinations other than ICS/formoterol, the use of ICS-formoterol as on-demand therapy is not recommended, as there is no evidence for the efficacy and safety of such a mixture and a risk of confusion by patients cannot be ruled out.

- Can (S)MART therapy be de-escalated? In asthma therapy, once good disease control has been achieved, usually after six months, it is necessary to de-escalate the therapy according to the step-by-step scheme. This applies primarily to the ICS dose. This approach has been shown to be safe, but any dose reduction carries the risk of loss of asthma control. This also applies to the (S)MART concept, which makes it possible to de-escalate therapy to an AIR-only concept in suitable patients with mild asthma. For patients with a high seasonal variability in the course of the disease, the variable treatment regimens offer the possibility of adapting the intensity of treatment to the course of the disease.

- Is (S)MART therapy suitable for patients with severe asthma and biologics therapy? The relevant studies on (S)MART therapy were conducted before the biologics were approved. However, there is no plausible reason to withhold the benefits of this therapy from these patients and all clinical experience suggests that patients undergoing biologic therapy also benefit from it. Accordingly, it is also recommended in the current guidelines.

- Are AIR and (S)MART suitable for children and young people? According to the evidence and the approvals, children and adolescents aged 12 years and over can be treated as needed with a fixed combination of ICS + formoterol from treatment level 3 according to the GINA classification (or from treatment level 4 according to the S2 specialist guideline for asthma) if this is also the long-term therapy. A purely demand-oriented application of a fixed combination of low-dose ICS + formoterol is also possible from the age of 12 in stages 1 and 2 in the GINA classification in accordance with the guidelines, although it should also be pointed out here that this therapy is not approved in the EU and Switzerland.

- Should ICS or (S)MART therapy be de-escalated after the introduction of biologics? One question that often arises in the clinic is whether ICS or (S)MART therapy can be de-escalated after the introduction of biologics. Most national and international guidelines recommend that biologics should only be used when asthma is inadequately controlled on the highest dose of ICS. A recently published study (SHAMAL study) shows that the dose of ICS can be reduced without exacerbations occurring with biologics. However, to date there is no recommendation for reducing ICS therapy under biologics [13].

Different ICS – are they all the same?

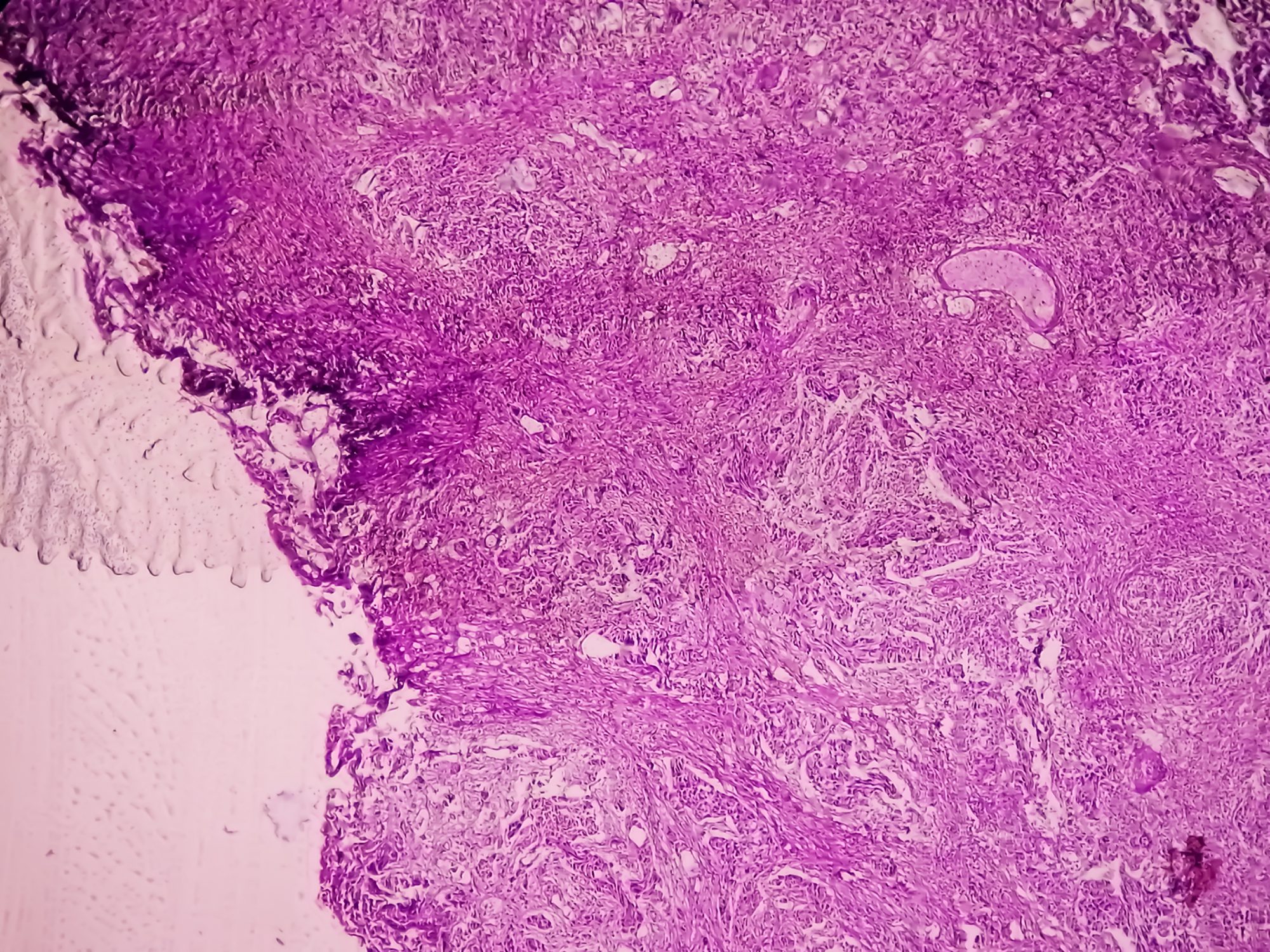

The available, molecularly different ICS such as budesonide, beclomethasone, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone, mometasone and triamcinolone differ in terms of pharmacokinetics, e.g. receptor affinity and protein binding, and therefore have different potencies. For example, there is a close correlation between receptor affinity and therapeutic efficacy. Table 1 also shows the differences in protein binding. However, the ICS are comparable in terms of pharmacodynamics, intracellular signaling pathways and ultimately the mechanisms of anti-inflammatory efficacy.

Dose dependence of ICS – effects and side effects

With regard to the therapeutically desirable, positive effects, such as improvement of asthma control, improvement of lung function, reduction of exacerbations and reduction of bronchial hyperreactivity, the dose-response relationships are not linear. High efficacy is already achieved at very low doses and the additional benefit increases more and more slowly with further dose increases and can reach a plateau at high doses. A study by Beasley et al. showed that 80% of the benefit achieved at 1000 µg/d was already achieved at a dose of 70-180 µg/d and 90% at a dose of 100-250 µg/d, so that a further increase no longer represented a relevant advantage [15]. On the other hand, inhaled and therefore local ICS therapy also has systemic effects and can therefore cause side effects. It has been shown that a daily dose of 1000 µg ICS corresponds to a dose of 2-5 mg oral prednisone in terms of the incidence of adrenal insufficiency. Side effects include the development and exacerbation of diabetes mellitus, the development of cataracts, a predisposition to osteoporosis and fractures and a slight reduction in length growth in children [16]. For these adverse systemic ICS effects, the dose-response relationships are characterized by a higher degree of linearity than the local bronchial effects.

It is therefore important to find and use the lowest ICS dose for the intended therapeutic benefit. It has proven useful to classify the different preparations into low, medium, high and maximum doses (Table 2) . In addition to the pharmacokinetic variables already described, the differences between the substances are also due to physical differences such as particle size. The type of administration (e.g. metered dose inhaler or powder inhalation) and the correctness of the application by the patient are also relevant.

In addition to the undesirable systemic effects, ICS can also cause local side effects, in particular hoarseness due to reversible myopathy of the vocal cords and oropharyngeal candidiasis. In this situation, if dose reduction and mouth rinses are not sufficiently effective, it may make sense to choose a medication such as ciclesonide, which is a prodrug and is only activated on the bronchial mucosa by esterases.

Methods of inhalation application of ICS

There are currently three methods for topical bronchopulmonary application of ICS: Metered dose inhalers (MDI), dry powder inhalers (DPI) and nebulizers. In MDIs, the drugs are either dissolved or suspended in a liquefied, pressurized propellant. When the MDI is triggered, a defined quantity of the propellant is converted into an aerosol that escapes from the opening at high speed. With MDIs, the patient must coordinate the deep inspiration well with the triggering of the MDI, which is difficult for some patients. Errors during application can significantly affect the ICS dose applied. In the case of MDIs, the use of spacers can provide relief, especially in children or older people, and both improve the effective inhaled ICS dose and minimize side effects, especially local side effects.

With dry powder inhalation (DPI), the release and administration of the medication is triggered by the patient’s inhalation; the medication is entrained by the inhaled air, which is why no synchronization between inhalation and device release is required. Nevertheless, misuse is also possible with DPI, which can have an unfavorable effect on the amount of medication inhaled.

Sufficient therapy with MDI or DPI is possible for the vast majority of asthma patients. When used correctly, the effectiveness is similar. However, it should be avoided if possible to combine DPI and MDI, as they require different breathing maneuvers, which can cause difficulties for some patients.

Nebulizers convert a liquid solution or suspension into an aerosol by using either a jet of compressed air or ultrasonic energy. The aerosol plume is then delivered to the patient via a mouthpiece. Face masks should be avoided due to the high nasal and cutaneous and comparatively low bronchial deposition and are only of value in younger children. Nebulizers place only minor demands on the patient’s inhalation technique. They are therefore generally only prescribed and used for patients who are unable to use either an MDI or a DPI, e.g. geriatric patients.

Take-Home-Messages

- ICS are the basis of asthma therapy. In addition to fixed application regimens, variable therapy concepts have been developed that are based on the variability of the course of the disease.

- The (S)MART approach, consisting of an ICS-formoterol combination for the treatment of patients in stages 3 to 5, has been shown to be superior for suitable patients.

- In recent years, it has been demonstrated that the purely demand-oriented application of ICS-formoterol fixed combinations also offers relevant advantages as AIR therapy for mild asthmatics in therapy stages 1 and 2. There is no longer an indication for SABA monotherapy.

Literature:

- Lommatzsch M, et al: The new specialist asthma guideline 2023: A companion and milestone in asthma care. Pneumology 2023; 77(08): 459-460.

- Lommatzsch M, et al: Disease-modifying anti-asthmatic drugs. The Lancet 2022; 399(10335): 1664-1668.

- Suissa S, et al: Low-Dose Inhaled Corticosteroids and the Prevention of Death from Asthma. New England Journal of Medicine 2000; 343(5): 332-336.

- Nwaru BI, et al: Overuse of short-acting β(2)-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA program. The European respiratory journal 2020; 55(4): 1901872.

- Nelson HS, et al: The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest 2006; 129(1): 15-26.

- Weatherall M, et al: Meta-analysis of the risk of mortality with salmeterol and the effect of concomitant inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Thorax 2010; 65(1): 39-43.

- Pauwels Romain A, et al: Effect of Inhaled Formoterol and Budesonide on Exacerbations of Asthma. New England Journal of Medicine JAHR?; 337(20): 1405-1411.

- Bateman ED, et al: Can Guideline-defined Asthma Control Be Achieved? American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2004; 170(8): 836-844.

- Rabe KF, et al: Effect of budesonide in combination with formoterol for reliever therapy in asthma exacerbations: a randomized controlled, double-blind study. The Lancet 2006; 368(9537): 744-753.

- Papi A, et al: Rescue Use of Beclomethasone and Albuterol in a Single Inhaler for Mild Asthma. New England Journal of Medicine 2007; 356(20): 2040-2052.

- O’Byrne PM, et al: Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma. New England Journal of Medicine 2018; 378(20): 1865-1876.

- Alberto P, et al: European Respiratory Society short guidelines for the use of as-needed ICS/formoterol in mild asthma. European Respiratory Journal 2023; 62(4): 2300047.

- Jackson DJ, et al: Reduction of daily maintenance inhaled corticosteroids in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (SHAMAL): a randomized, multicentre, open-label, phase 4 study. The Lancet 2024; 403(10423): 271-281.

- Baptist AP, Reddy RC: Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma: are they all the same? Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2009; 34(1): 1-12.

- Beasley R, et al: Inhaled Corticosteroid Therapy in Adult Asthma. Time for a New Therapeutic Dose Terminology. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2019; 199(12): 1471-1477.

- Heffler E, et al: Inhaled Corticosteroids Safety and Adverse Effects in Patients with Asthma. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2018; 6(3): 776-781.

- Lipworth B, et al: Anti-inflammatory reliever therapy for asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2020; 124(1): 13-15.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2024; 6(2): 6-11