Glioblastomas are a particularly aggressive form of brain tumor. To this day, they are incurable. Despite important advances in understanding the molecular pathogenesis and biology of this tumor over the past decade, the prognosis for patients remains poor. New strategies, current challenges and future directions for the discovery of new biomarkers and therapeutic targets need to be further explored.

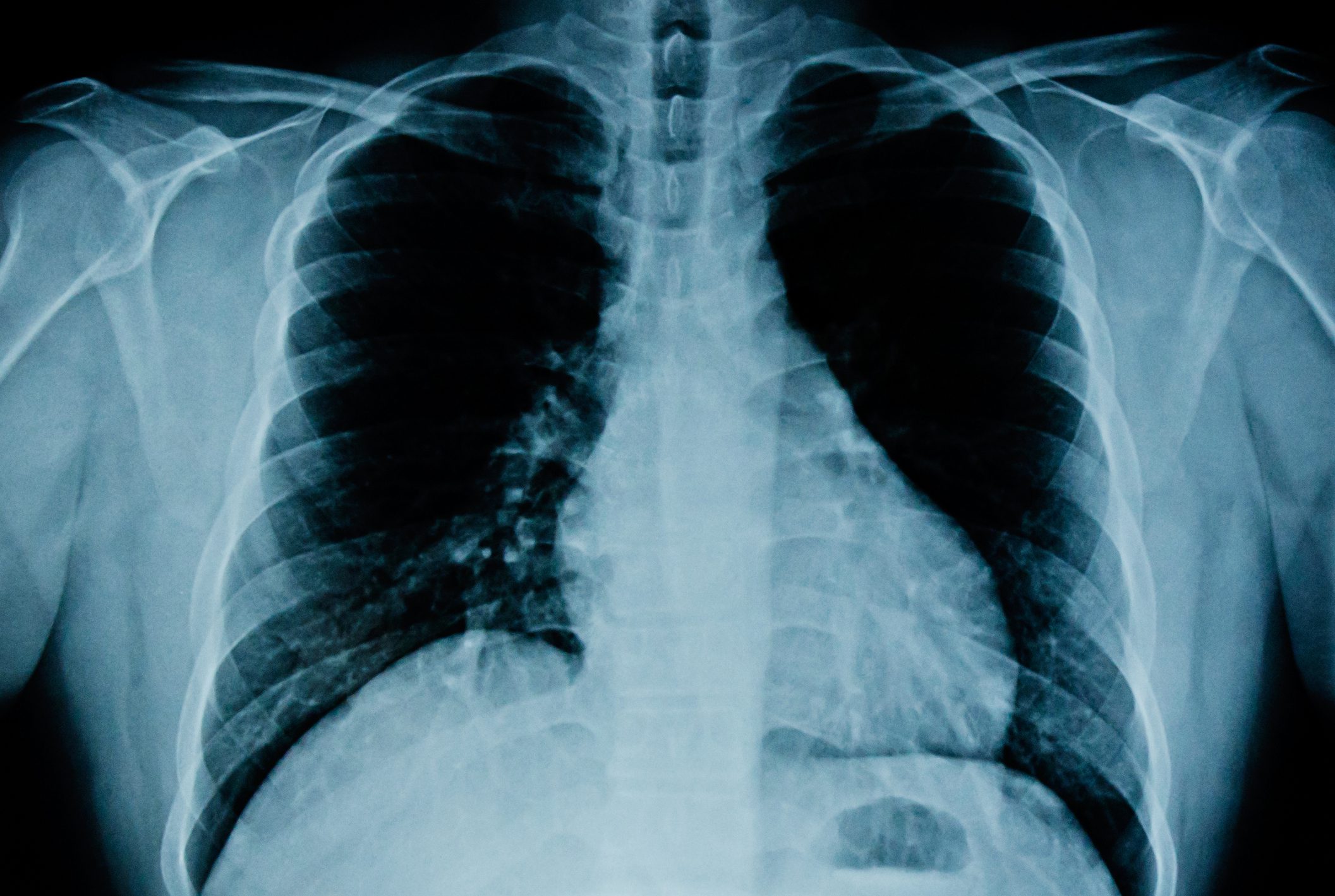

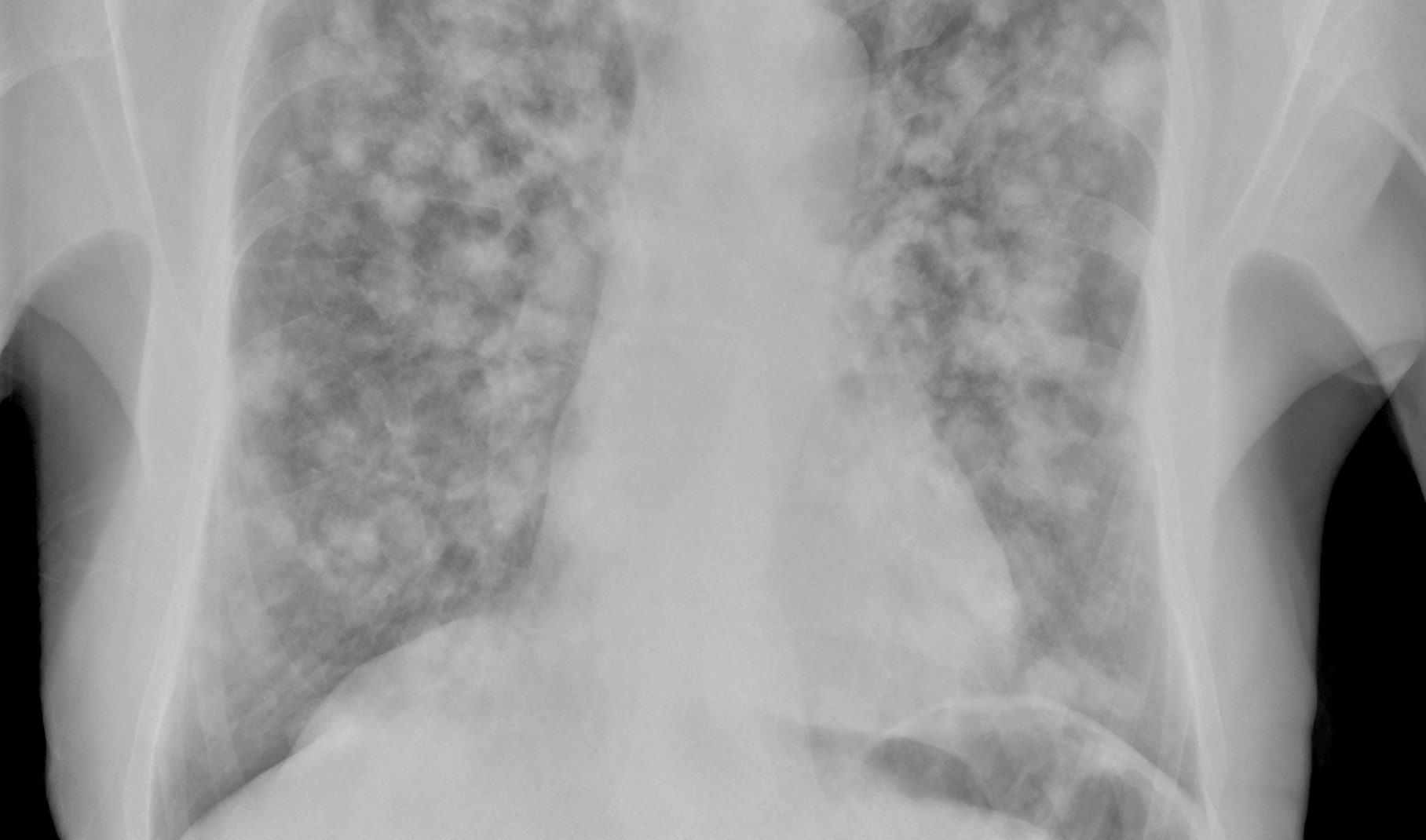

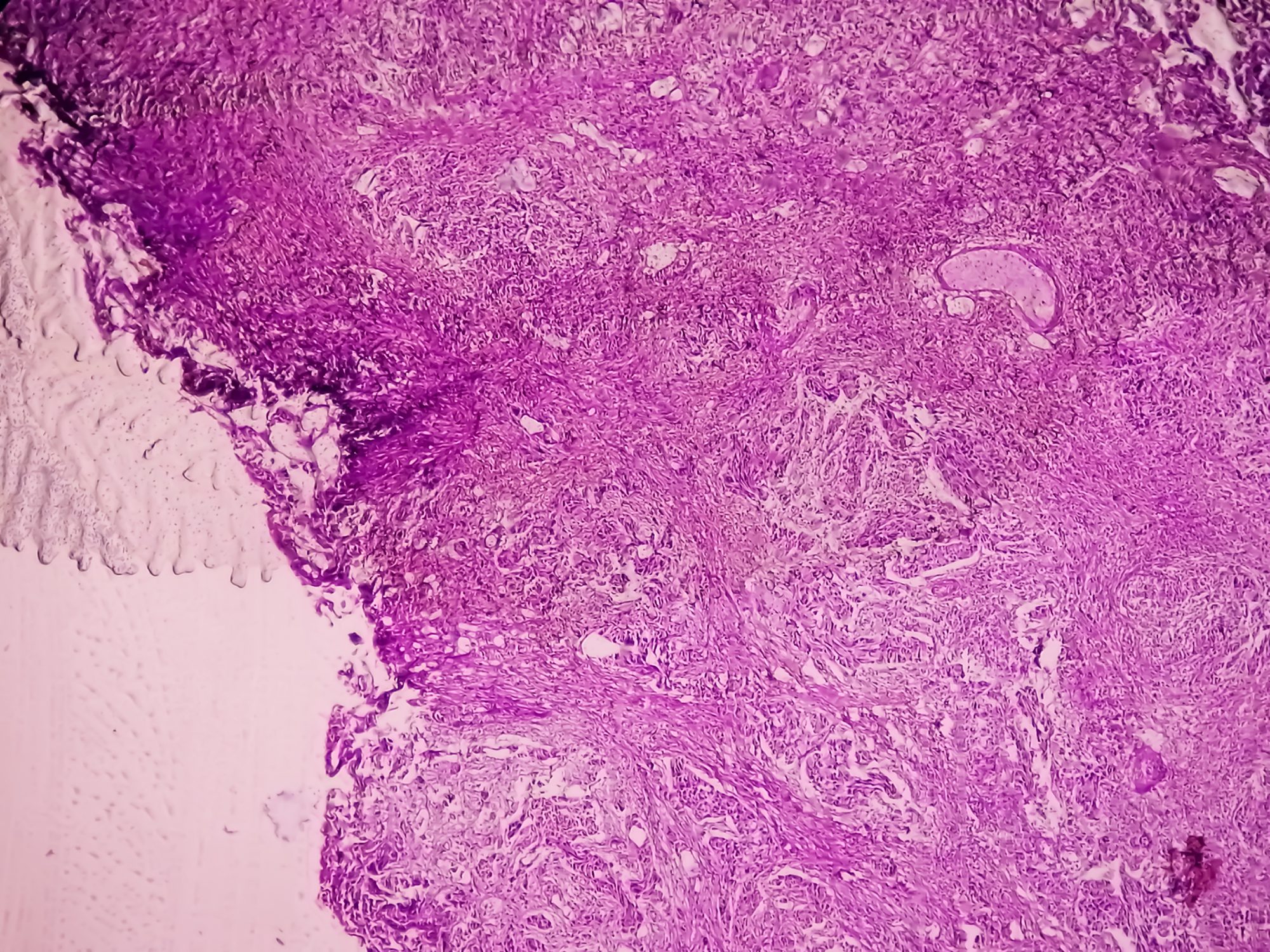

Every year, about 600 people in Switzerland develop a brain tumor [1]. At 55%, glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumor in adults and is currently incurable [2]. It arises from the supporting cells of the brain, can occur anywhere in the brain, and usually affects people between the ages of 50-70. They grow along fiber tracts in the brain, spreading locally, regionally, and nationally. The hallmarks of glioblastoma in tissue examination under the microscope are minute vascular neoplasms, cell divisions, and zones of cell death. Rare variants of glioblastoma are gliosarcoma, giant cell glioblastoma and epithelioid glioblastoma. The risk factors for developing glioblastoma are not yet fully understood. Only irradiation of the head could be detected as causative. Hereditary factors only play a subordinate role.

Correctly classifying heterogeneous tumors

Although a histopathology-based morphological classification provides important information for the diagnosis of a glioblastoma, it has the disadvantage that it cannot reflect the heterogeneity of the tumors and is therefore insufficient for patient management. When the WHO classification of CNS tumors (CNS 4) was revised in 2016, the classification of GBM was therefore restructured by including molecular features in the histopathological manifestations. For example, IDH mutation status was included for the diagnosis of GBM to categorize patients into different subgroups, namely glioblastoma, IDH wild-type and glioblastoma, IDH mutant-type. IDH wild-type glioblastoma corresponds to the clinically defined primary glioblastoma, which is characterized by de novo development without a recognizable precursor lesion. This group accounts for the overwhelming majority of glioblastoma patients (around 90%), is diagnosed more frequently in older patients and has a more aggressive clinical course. In contrast, IDH-mutated glioblastoma or secondary glioblastoma typically arises from a diffuse or anaplastic astrocytoma precursor. This group accounts for approximately 10% of patients and predominates in younger patients with a median age at diagnosis of 44 years, generally conferring a better prognosis [2]. This shift towards molecular classification of primary brain tumors is further emphasized in the 2021 revised WHO classification of CNS tumors (CNS 5), which includes more molecular features as part of the definition of gliomas. These include CDKN2A/B homozygous deletion mutation, TERT promoter mutation, EGFR gene amplification and the combined gain of the entire chromosome 7 and loss of the entire chromosome (+7/-10) as a prerequisite for the diagnosis of GBM, IDH wild type [2].

A lot helps a lot – but not enough

Currently, glioblastomas are treated with a combination of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy – the Stupp regimen. The operation relieves the main tumor mass without generating deficits. The prognosis can also be improved in this way. However, only temporarily, until the mass has regenerated. Another treatment option is to use radiation to stop the cells in a growth phase of the cell cycle. This also often succeeds very well. However, the same applies here as with the operation: the deeply branched cells cannot be addressed. And finally, chemotherapy can be used. So far, temozolomide has been used as primary therapy – combined with lomustine depending on the molecular profile, age and clinical-neurological condition. Quite successfully. However, only in one-third of affected individuals who do not show resistance to alkylating chemotherapy. And even in these, the disease progresses again after a certain time and recurrence occurs [3]. The treatment strategy for progression is coordinated on an interdisciplinary basis, based on various criteria, including the clinical condition, the latency to first-line therapy and the imaging pattern of progression. Clinical therapy trials are an integral part of glioblastoma treatment at every stage of the disease. Current clinical therapy trials are investigating biomarker-based therapy strategies, various immunotherapy strategies or the further optimization of previous therapy concepts [4].

Literature:

- www.krebsliga.ch/ueber-krebs/krebsarten/hirntumoren-und-hirnmetastasen (last accessed on 05.12.2024).

- Lan Z, Li X, Zhang X: Glioblastoma: An Update in Pathology, Molecular Mechanisms and Biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Mar 6; 25(5): 3040.

- Venkataramani V, Yang Y, Schubert MC, et al.: Glioblastoma hijacks neuronal mechanisms for brain invasion. Cell 2022; 185(16): 2899–2917.

- Rieger D, Reovanz M, Kurz S, et al.: Glioblastom – aktuelle Therapiekonzepte. Die Onkologie 2024.

InFo ONKOLOGIE & HÄMATOLOGIE 2024; 12(6): 24