At the 55th Continuing Medical Education in Davos in January 2016, a workshop focused on the correct use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI). Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Beglinger, Claraspital Basel, explained the effects and side effects of these active substances and pleaded for them not to be prescribed lightly, but only when clearly indicated. While PPIs are generally well tolerated, they can also cause adverse side effects with long-term treatment.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are among the most commonly prescribed drugs because they are highly effective, well tolerated – and are also cleverly marketed, the speaker noted. One dose of a PPI (e.g., 40 mg pantoprazole) irreversibly inhibits acid production for 12-16 hours until new proton pumps are produced. The efficacy of each preparation in terms of cure rates for gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) or ulcer disease is equivalent, studies show.

The right time to take it: half an hour before a meal

The active ingredients taken are pro-drugs; they are not activated in the stomach until acid is present. Oral bioavailability is good, but the half-life is short. Therefore, the correct time of intake is very important, namely about half an hour before breakfast or breakfast. before the meal: Then the maximum plasma concentration of the PPI falls together with the activation of the proton pumps. “About one-third of all physicians, however, unfortunately do not instruct patients properly,” Prof. Beglinger said.

Most PPIs are metabolized by CYP2C10 and CYP3A4; therefore, factors such as hepatic insufficiency, age, or mutations in CYP2C19 reduce clearance. In general, PPIs are well tolerated, with gastrointestinal side effects such as diarrhea, constipation, and flatulence being the most common. Discontinuation of PPIs may result in a rebound phenomenon with recurrence of symptoms, so PPIs should be phased out slowly.

Indications for PPI

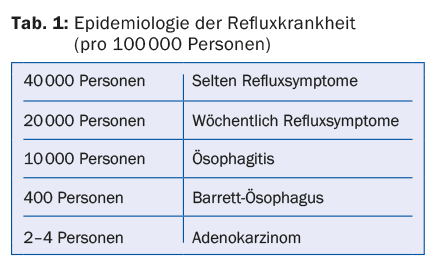

Indications for PPI use include reflux disease, ulcer disease, and ulcer prevention. In reflux, three explicit disease patterns are distinguished: GERD, erosive esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus (Table 1) . They can all be mild or severe. “Reflux stenosis, which used to be common, has fortunately almost disappeared today thanks to medications,” Prof. Beglinger mentioned. The most important therapeutic goal in GERD is symptom control. In cases of endoscopically proven esophagitis, one should aim to heal the lesions to prevent complications and document healing endoscopically. If typical GERD symptoms are present and endoscopic findings are unknown, empiric PPI treatment for four weeks is appropriate. If the patient is then symptom-free, PPIs can be prescribed in low doses as an on-demand medication. If there is no improvement after four weeks, endoscopic clarification should be performed.

For eradication of H. pylori, standard therapy consists of administration of a PPI plus two antibiotics. There is no consensus on the duration of eradication treatment (7 or 14 days), but recent data indicate that therapy for at least 14 days with a PPI plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin resp. PPI plus amoxicillin and nitroimidazole significantly increased the eradication rate.

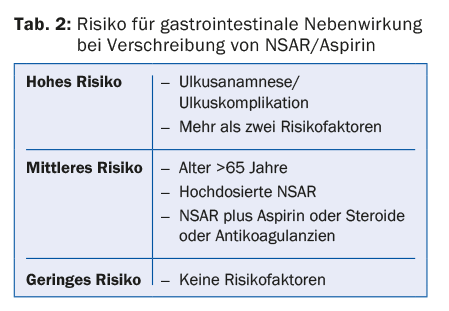

Ulcer prophylaxis with PPI when prescribing NSAIDs and aspirin is established and useful – but only if the patient has an appropriate risk profile (tab. 2). “Patients without a risk profile do not need PPI prophylaxis,” the speaker explained.

Are PPIs prescribed too often?

Various studies show that PPIs are often prescribed without proper indication. For example, patients receive perioperative PPI prophylaxis in the hospital, and later, at discharge, the PPI is still on their medication list. Another problem is false indications such as gastritis or undifferentiated “gastric protection”. The side effects of such an often inappropriate long-term treatment can be significant: Decrease in vitamin B12 levels (data is unclear, however), decreased iron absorption with anemia, or reduced absorption of calcium and vitamin D, which increases the risk of osteoporotic fractures.

Population-based studies also show an association between PPI use and Clostridium difficile infections (risk increase 2.5-2.9). “While causality cannot be inferred from this,” the speaker said. “Still, I recommend caution with long-term PPI prescribing in patients who are at increased risk for C. difficile infection, for example, those on antibiotic therapy, advanced age, or renal insufficiency.” PPIs also increase the risk for community-acquired pneumonia.

Take home messages

- PPIs are effective and safe medications, but they should be prescribed only for clear indications.

- PPIs are prescribed too often – even in situations where there is no proven benefit.

- Long-term therapies must be well justified.

- Especially in the elderly, the lowest possible doses should be aimed for.

- It is important to know the potential side effects of PPIs.

Source: 55th Continuing Medical Education Davos, January 7-9, 2016

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(3): 56-57