Direct and indirect immunofluorescence are still the gold standard for the detection of specific antibodies and autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid. Highly effective topical steroids or systemic corticosteroids are recommended as first-line therapy. In the event of a lack of response or contraindications, immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive drugs can be used. According to several case reports, omalizumab and dupilumab have proven to be effective treatment options and further biologics are currently being researched.

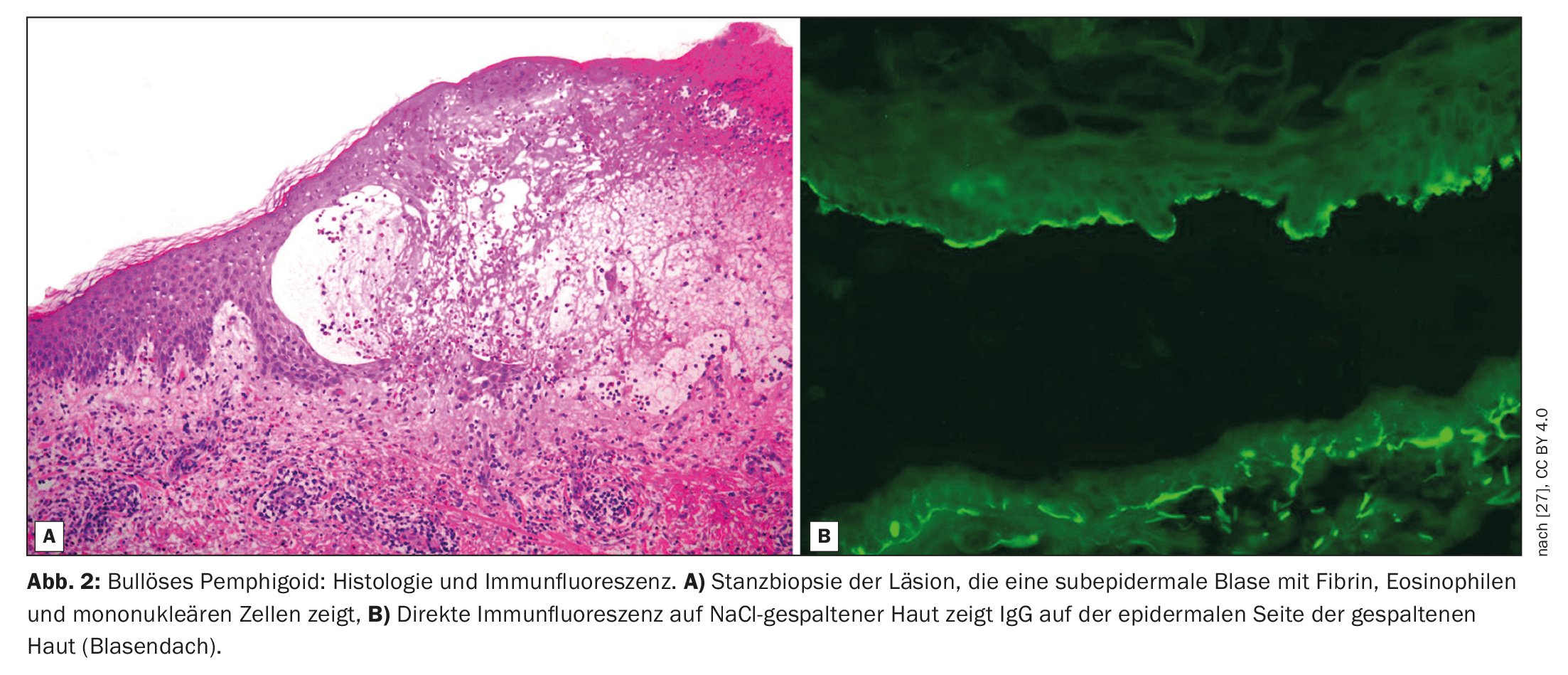

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is characterized by subepidermal blistering, i.e. blistering within the dermoepidermal junction zone (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) [1]. It is the most common bullous autoimmune dermatosis in Switzerland and Europe, reported Prof. Dr. med. Luca Borradori, Clinic Director and Chief Physician, University Clinic for Dermatology, Inselspital Bern [2]. In recent decades, an increase in the incidence of BP has also been observed in this country. An ageing population, the association with increasingly common neurological diseases and certain medications, as well as an increased awareness of atypical variants without blistering are discussed as possible causes for this [28]. The treatment of BP aims to bring the disease under control, alleviate itching symptoms and improve the quality of life of those affected. The treatment methods depend primarily on the severity of the disease. According to Prof. Borradori, attention should be paid to a favorable risk-benefit profile of the respective treatment.

Clinical suspicion of BP: serology provides certainty

The diagnosis of BP is based on a combination of criteria, including clinical features, light microscopic findings and detection of autoantibodies in the skin by direct immunofluorescence (DIF) [3]. The classic clinical manifestation of BP is a very itchy rash with generalized blistering (bulging, itchy blisters of varying sizes filled with serous fluid). In early stages or in atypical variants, however, only localized or generalized excoriated, eczematous or urticarial lesions may be present [4]. The mucous membranes are affected to 10-30%. The typical finding in direct immunofluorescence is the detection of linear immunoglobulin (Ig)G bound to the dermo-epidermal junction zone, more rarely also IgM and IgA. These autoantibodies primarily bind the proteins BP180 and BP230, which are components of the hemidesmosomes. These represent an important cellular connection and have an essential function for the mechanical stability of the skin [1].

In order to confirm the suspected diagnosis of BP, the following further laboratory diagnostic clarification steps are recommended in the s2K guidelines of an EADV expert group, updated in 2022 [3]:

- Detection of circulating IgG autoantibodies against the basement membrane zone (BMZ) by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (IIF) using normal human skin cleaved with NaCl solution.

- Detection of anti-BP180-NC16A IgG autoantibodies and/or anti-BP230 IgG autoantibodies by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay).

- The novel “multivariate” tests are also recommended for the detection of circulating anti-BMZ IgG autoantibodies. These BIOCHIP mosaic assays combine different antigenic substrates. In the rare cases of BP in which circulating anti-BMZ antibodies are not detectable by either indirect immunofluorescence microscopy or commercially available ELISA, it is recommended that additional testing be performed to increase diagnostic sensitivity and rule out other autoimmune diseases of the dermo-epidermal junction (especially anti-P200 pemphigoid or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita). An overview of the relevant tests can be found in the s2K guidelines published in JEADV [3].

Pathophysiology: complement-independent mechanisms also involved

The pathophysiological relationships in BP are very complex [4]. On the one hand, activation of the complement system with the production of anaphylatoxins and activation of the innate immune response with subsequent recruitment and activation of basophils, eosinophils, neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages and mast cells play a key role in BP [5,6, 28-31]. On the other hand, researchers have increasingly discovered complement-independent inflammatory mechanisms in connection with BP antibodies in recent years. Keratinocytes in particular appear to be able to secrete a large number of proinflammatory pathogenetically relevant cytokines [4,7,32].

One study showed that both BP-IgG and BP-IgE are able to bind directly to the surface of cultured human keratinocytes, with subsequent loss of hemidesmosomes at the basement membrane zone [8]. Eosinophils are involved in BP pathogenesis by mediating the effects of anti-BP180 IgE antibodies and contributing to dermo-epidermal separation. In the presence of IgG or IgE, eosinophils can directly mediate dermo-epidermal separation [9,10]. Freire et al. found elevated levels of both anti-BP180 and anti-BP230 IgE using ELISA and immunofluorescence compared to healthy controls [11].

Anti-BP180 IgE autoantibodies are present in the majority of BP patients, and their levels correlate with disease activity [12–15]. In addition, direct immunofluorescence studies have shown that the majority of BP patients had IgE+ cells in their skin, in contrast to healthy controls. Overall, the evidence suggests that there is an additional complement-independent, Th2-dependent, eosinophil-mediated pathway that contributes to tissue damage and clinical features in BP [4].

| “Treat-to-target” with progress monitoring and follow-up |

| – The EADV expert group generally recommends a treatment duration of between 9 and 12 months for BP [3]. |

| – Discontinuation of treatment is recommended in patients who have been symptom-free for at least 1-6 months on minimal therapy with oral prednisone (0.1 mg/kg/day), clobetasol propionate (10 g/week) or immunosuppressants. Discontinuation of treatment is also influenced by the patient’s general condition and the presence of certain comorbidities. |

| – anti-BP180 ELISA (i.e. >27 U/mL as determined by the MBL** test) and to a lesser extent DIF$ studies have been reported to have predictive value for the occurrence of relapse after discontinuation of treatment [24]. It may be worth considering using these tests before discontinuing treatment. |

| – In addition, attention should be paid to possible adrenal insufficiency caused by the use of exogenous corticosteroids (CS) (also after the use of topical CS). |

| A follow-up examination is recommended in the third month after discontinuation of treatment. This period appears to be sufficient to detect most BP relapses [24–26]. Irrespective of this, recurrence of itching, excoriations and/or inflammatory skin lesions should always be clarified by a doctor. |

| ** MBL= Medical & Biological Laboratories $ DIF=Direct Immunofluorescence |

New treatment options: Biologics as an alternative therapy

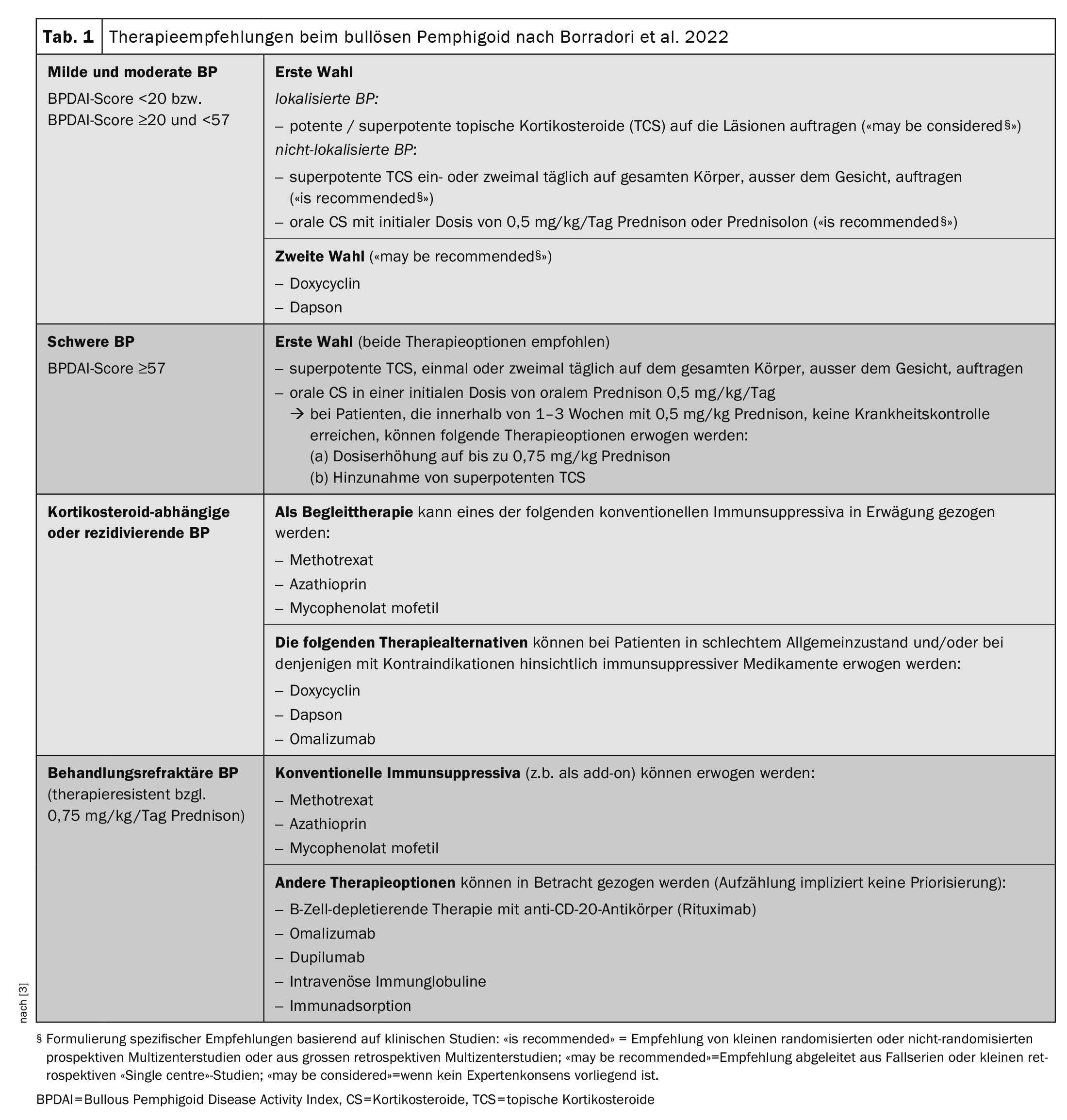

Table 1 [3] provides an overview of the currently available treatment options. The guidelines continue to recommend the use of superpotent topical corticosteroids (TCS) or systemic steroids (prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/d) as first-line therapy. In many cases, the symptoms can be contained, but “you have to be patient,” explained Prof. Borradori [2]. The estimated duration of treatment is 9-12 months. However, there are also patients for whom standard therapy is not effective or is contraindicated. “We need good, new and effective therapies,” emphasized the speaker [2]. The observation that patients with BP often have elevated serum IgE levels and circulating BP180- and BP230-specific IgE autoantibodies supports the idea that IgE plays a role in BP pathogenesis [16,17]. The use of omalizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits IgE binding to its high-affinity receptor (FcεRI), is therefore an obvious choice. Case reports show that omalizumab therapy leads to a strong decrease in FcεRI expression on circulating basophils and a strong reduction of FcεRI + cells in the skin of treated patients [16].

Other biologic targeted therapies that have shown promise in BP include dupilumab, a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to the α-subunit of the IL-4 receptor, thereby inhibiting IL-4/IL-13 signaling pathways [18–21]. “We have many case series that show that dupilumab has a good effect in patients with bullous pemphigoid,” reported Prof. Borradori [19,22]. The biologic proved to be effective both as monotherapy and in combination with a standard therapy. Following successful clinical testing in Phase II, the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in BP is currently being investigated in the Phase III LIBERTY-BP study (NCT04206553) [23].

Congress: Joint advanced training BE-BS-ZH

Literature:

- Diagnosis and treatment of pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid, AWMF guideline S2k 2019, German Dermatological Society e.V. (DDG), AWMF register no.: 013-071.

- “Therapy of bullous pemphigoid: practical procedure”, Prof. Dr. med. Luca Borradori, Joint continuing education and training of the dermatology clinics of Bern, Basel, Zurich, Inselspital Bern, 25.05.2023.

- Borradori L, et al: Updated S2 K guidelines for the management of bullous pemphigoid initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36(10): 1689-1704.

- Cole C, et al: Insights into the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: the role of complement-independent mechanisms. Compass Dermatol 2022; 10 (4): 171-180.

- Liu Z, et al: Subepidermal Blistering Induced by Human Autoantibodies to BP180 Requires Innate Immune Players in a Humanized Bullous Pemphigoid Mouse Model. J Autoimmun 2008; 31(4): 331-338.

- Liu Z, et al: Synergy Between a Plasminogen Cascade and MMP-9 in Autoimmune Disease. J Clin Invest 2005; 115(4): 879-887.

- Bao L, et al: Subunit-Specific Reactivity of Autoantibodies Against Laminin-332 Reveals Direct Inflammatory Mechanisms on Keratinocytes. Front Immunol 2021; 12: 775412.

- Messingham KN, et al: FcR-Independent Effects of IgE and IgG Autoantibodies in Bullous Pemphigoid. J I 2011; 187(1): 553-560.

- Amber KT, et al: The Role of Eosinophils in Bullous Pemphigoid: A Developing Model of Eosinophil Pathogenicity in Mucocutaneous Disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018; 5: 201.

- de Graauw E, et al: Evidence for a Role of Eosinophils in Blister Formation in Bullous Pemphigoid. Allergy 2017; 72(7): 1105-1113.

- Freire PC, Munoz CH, Stingl G: IgE Autoreactivity in Bullous Pemphigoid: Eosinophils and Mast Cells as Major Targets of Pathogenic Immune Reactants. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177(6): 1644-1653.

- Hashimoto T, et al: Detection of IgE Autoantibodies to BP180 and BP230 and Their Relationship to Clinical Features in Bullous Pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177(1): 141-151.

- van Beek N, et al: Correlation of Serum Levels of IgE Autoantibodies Against BP180 With Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Activity. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153(1): 30-38.

- Bing L, et al: Levels of Anti-BP180 NC16A IgE do Not Correlate With Severity of Disease in the Early Stages of Bullous Pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol Res 2015; 307(9): 849-854.

- Salz M, et al: Elevated IL-31 Serum Levels in Bullous Pemphigoid Patients Correlate With Eosinophil Numbers and Are Associated With BP180-IgE. J Dermatol Sci 2017; 87(3): 309-311.

- Seyed Jafari SM, et al: Effects of Omalizumab on FcεRI and IgE Expression in Lesional Skin of Bullous Pemphigoid. Front Immunol 2019; 10: 1919.

- Messingham KN, Crowe TP, Fairley JA: The Intersection of IgE Autoantibodies and Eosinophilia in the Pathogenesis of Bullous Pemphigoid. Front Immunol. 2019;10: 2331.

- Abdat R, et al: Dupilumab as a Novel Therapy for Bullous Pemphigoid: A Multicenter Case Series. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83(1): 46-52.

- Zhang Y, et al: Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Moderate-To-Severe Bullous Pemphigoid. Front Immunol 2021; 12: 738907.

- Seyed Jafari SM, et al: Case Report: Combination of Omalizumab and Dupilumab for Recalcitrant Bullous Pemphigoid. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 611549.

- Kaye A, et al: Dupilumab for the Treatment of Recalcitrant Bullous Pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154(10): 1225-1256.

- Klepper EM, Robinson HN: Dupilumab for the treatment of nivolumab-induced bullous pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27(9): 1-6.

- US National Library of Medicine. A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Adult Patients With Bullous Pemphigoid (LIBERTY-BP). Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine (2019).

- Bernard P, et al: Risk factors for relapse in patients with bullous pemphigoid in clinical remission: a multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Arch Dermatol 2009; 145: 537-542.

- Joly P, et al: A comparison of two regimens of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with bullous pemphigoid: a multicenter randomized study. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129: 1681-1687.

- Fichel F, et al: Clinical and immunologic factors associated with bullous pemphigoid relapse during the first year of treatment: a multicenter, prospective study. JAMA Dermatol 2014; 150: 25-33.

- Michelerio A, Tomasini C: Blisters and Milia around the Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter: A Case of Localized Bullous Pemphigoid. Dermatopathology 2022; 9(3): 282-286. www.mdpi.com/2296-3529/9/3/33,(last accessed 10.08.2023).

- Holtsche MM, Boch K, Schmidt E: J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2023; 21(4): 405-413.

- Chen R, et al: J Clin Invest 2001; 108(8): 1151-1158.

- Nelson KC, et al: J Clin Invest 2006; 116(11): 2892-900.

- Leighty L, et al: Arch Dermatol Res 2007; 299(9): 417-422.

- Schmidt E, et al: J Invest Dermatol 2000; 115(5): 842-848.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2023; 33(5): 50-52 (published on 30.10.23, ahead of print)