Training stimuli trigger adaptations in the organism, regardless of age. The human organism is characterized by high plasticity and adaptability throughout the life span. As we age, declining hormone levels reduce the effectiveness of exercise, but it never becomes completely ineffective. Sport is therefore still possible and efficient even in old age.

Aging processes in the spine and joints already begin after the age of 30, so they are not just a problem of the older generation. Normal physical changes in the aging process include loss of fluid, loss of elasticity, loss of flexibility, extensibility and resilience of muscles, ligaments and joints. In addition, with aging, a decrease in stamina, responsiveness, sense of balance, and fine motor skills takes place. All these properties can be improved by targeted training, i.e. the aging process can be efficiently counteracted with sport and exercise.

Of course, the body’s reactions to training stimuli depend on the respective phase of life: children would not yet build up mountains of muscle during strength training. During puberty, the testosterone surge in adolescents leads to increased muscle responsiveness and therefore a greater training effect. In turn, as we age, declining hormone levels reduce the effectiveness of exercise. Nevertheless, there is now agreement that training effects are possible for all motor skills (strength, endurance) and abilities (balance, equilibrium, responsiveness) across the lifespan.

In contrast, physical inactivity quickly leads to negative adaptation processes or a decline in performance and increases the likelihood of so-called physical inactivity deficiency diseases. These include obesity, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, and also cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and myocardial infarction. Furthermore, inactivity can promote cerebral circulatory disorders as well as lead to a decrease in brain function or dementia. Last but not least, the danger of falling and the risk of bone fractures increase.

Those who already lead an inactive lifestyle at the age of 45 will feel the onset of old age frailty at the age of 65 at the latest, while those who are sporty from the age of 55 onwards can postpone such ailments until 85. The goals of regular training in old age are:

- No youth mania, but preservation of health

- Not necessarily a longer life, but improving the quality of life

- Prevention of inactivity-related diseases.

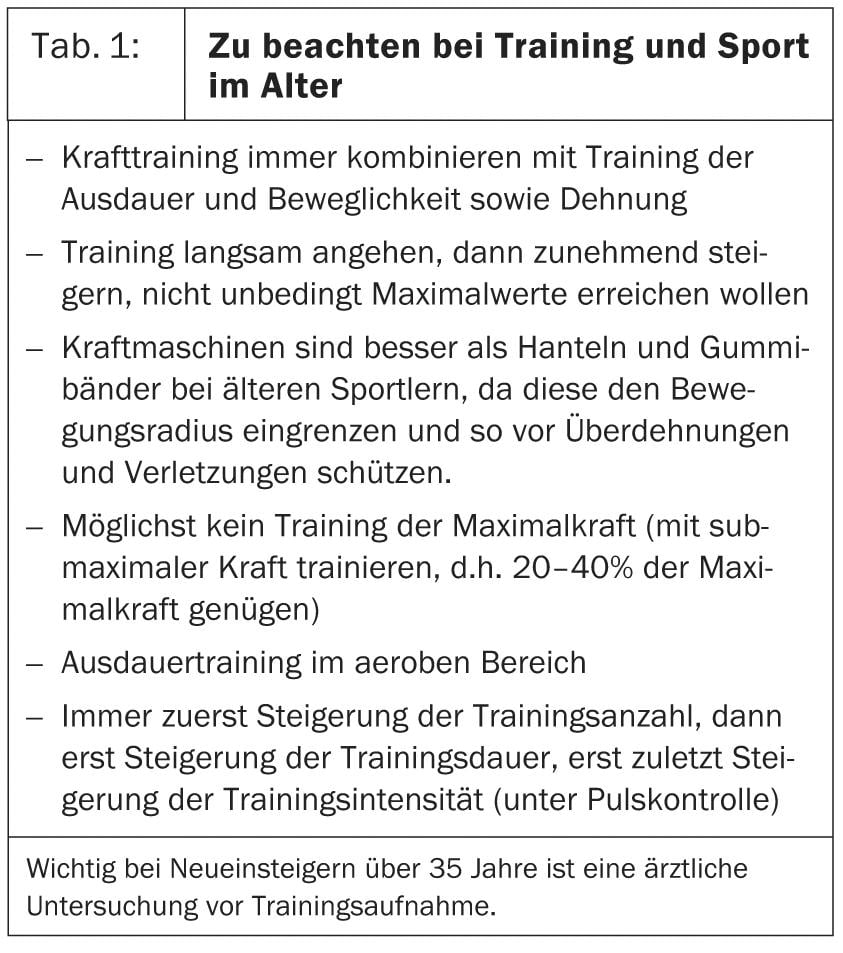

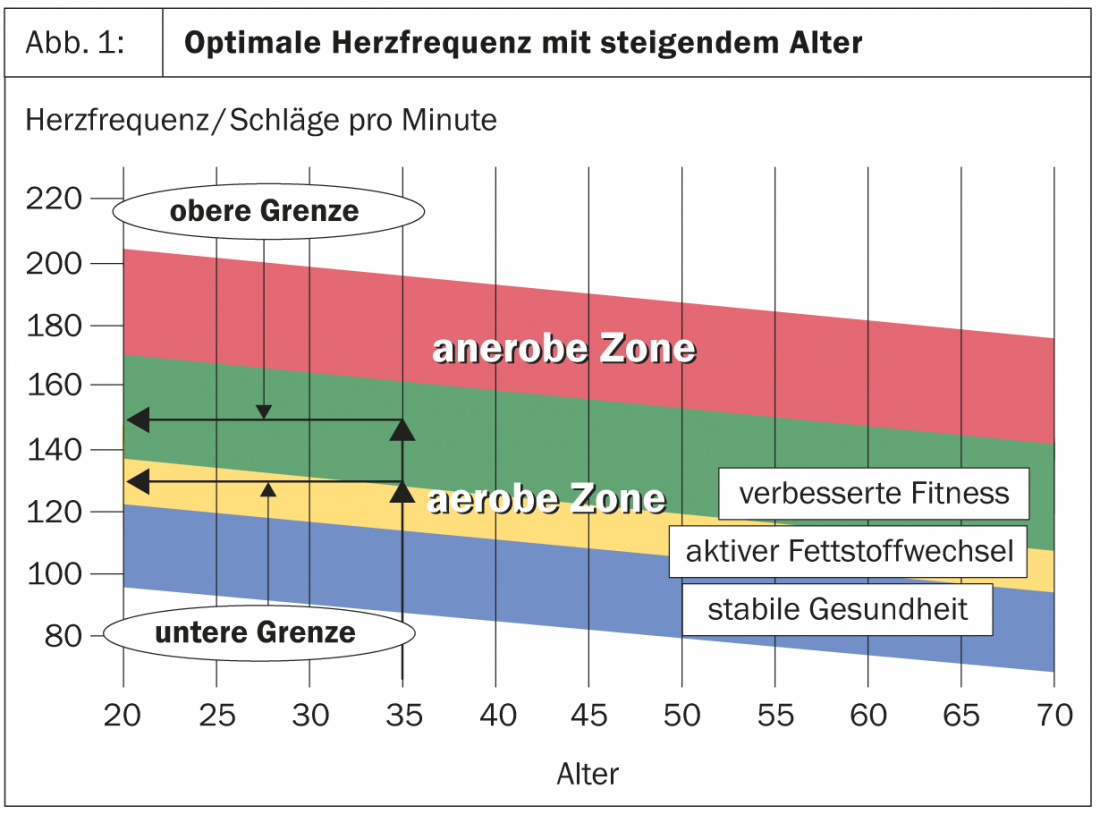

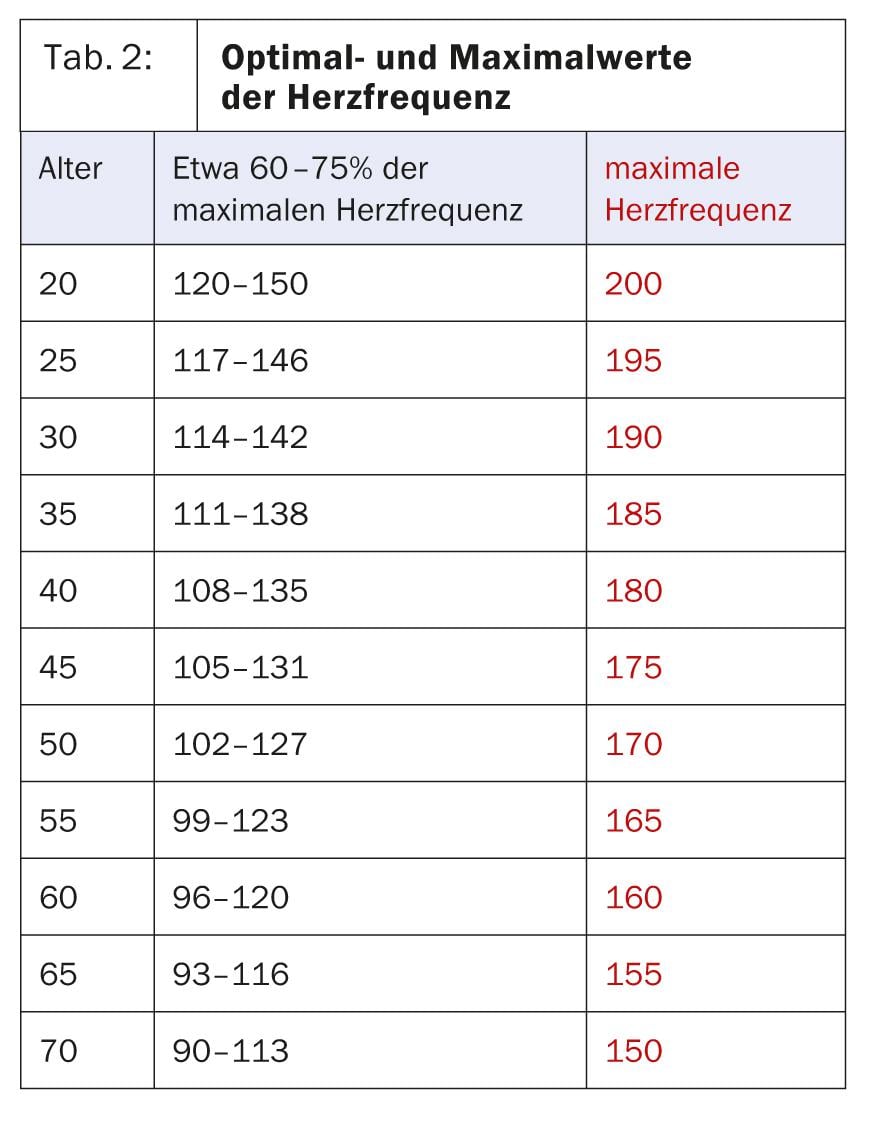

Table 1 goes into more detail about which factors to consider. Figure 1 and Table 2 show the optimal training heart rates with increasing age.

A definite increase in strength (up to 200%) can be achieved into old age. Strength training and physical conditioning sometimes also have a positive impact on walking speed and responsiveness.

Endurance and strength can be trained even in old age

Endurance performance is a relatively developmentally neutral ability: even school-age children can train endurance effectively, and this trainability is subject to little change into old age. However, this only applies to the overall extent of adaptability, while the speed of adaptation seems to decrease with age.

Strength can also be promoted in childhood, but can only be optimally trained after the onset of puberty, when the effect of testosterone is added. Even in retirement age, men and women achieve a substantial increase in maximum strength as well as strength/endurance through strength training, which is simultaneously accompanied by a training-induced, measurable muscle cross-sectional increase. Even in the tenth decade of life, significant strength gains and thus an increase in muscle cross-section, i.e. muscle mass, is still achievable in both sexes, as various studies and examples show. Even seniors can reach the performance level of an untrained 20- to 30-year-old through targeted strength training.

The Performance age competition exercise (PACE) study used the running times of marathon runners aged 20-79 to show that a quarter of 65- to 69-year-olds run faster than half of 20- to 54-year-olds.

Aging does not have to be a story of loss

Performance losses in middle and old age are mainly due to inactive lifestyles and not only to biological aging. Studies show the loss of 20-40% of muscle mass between the ages of 20 and 70. The decrease in endurance performance without training from the age of 30 is up to 15% per decade.

In the study “Bewegtes Alter” of the Jacobs University Bremen it could be shown that endurance or fitness training three times a week triggers positive effects regarding cognition/activation patterns in the brain. Merely performing relaxation exercises and stretching programs, on the other hand, shows no effect on the brain.

Sport in old age seems to keep gray brain cells fit. However, the hypothesis that regular exercise can also generally improve mental health status cannot be supported by meta-analyses. However, a recent study (2005) on the relationship between physical activity and psychological well-being in older people shows significant differences in subjective well-being between the physically active and the physically inactive. Endurance training led to the greatest effects, followed by strength training and general fitness training. Gender differences could not be detected.

Recommended sports in old age

Sports that are favorable are those that involve as little body checking as possible, no impact on the back and joints, and no risk of falling or injury. Endurance sports such as hiking, mountain walking, Nordic walking, biking, spinning, swimming, aqua jogging/WetVest training, golf, adapted gymnastics and adapted strength training are recommended. Other possible and suitable sports are those that train responsiveness and agility, such as table tennis, tennis, cross-country skiing, rowing and dancing.

Taking up strength and endurance training can be started at any age, following the motto: “It’s never too late!”

Gerda Hajnos-Baumgartner, M.D.

Literature:

- Christensen K, et al: Physical and cognitive functioning of people older than 90 years. Lancet 2013 published online July 11 2013.

- Conzelmann A: Faszination Sport, Unipress 132 / 2007.

- Leyk D, et al: Physical performance in middle age and old age good news for our sedentary and aging society. Also published as Physical performance in middle age and old age. Good news for an inactive and aging society. Dtsch Ärztebl int 2010; 107 (46); 809-16.

- Leyk D, et al: The PACE study – Lifestyle, health and performance. In: F.I.T.-Wissenschaftsmagazin der DSHS Köln 2009; 2: 38-42.

- Lüscher G, et al: Look inside get access. Social and Preventive Medicine 2001; 46(1): 41-48.

- Schlicht W: Mental health through sport – reality or wish: a meta-analysis. Journal of Health Psychology 1993, 1(1): 65-81.

- Schott N, Schlicht W: Physical activity and successful aging. In Fuchs R, Schlicht W (Eds.): Mental health and physical activity. Göttingen: Hogrefe 2012; 315-336.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 8 (10): 13-15