Platelet-rich plasma” (PRP) has established itself as a useful option for autologous reinjection in the regenerative medicine of numerous specialties for the therapy of disturbed healing processes. Standardized manufacturing process technology enables platelet-rich plasma to be produced consistently and with reproducible high quality. With these quality assurance “standards,” physicians and patients can benefit from reliable, high-quality care.

Much has happened since the first “experimental” clinical applications of platelet concentrates from autologous blood were described in dentistry over 60 years ago. In the meantime, “platelet-rich plasma” (PRP) for autologous reinjection has become established in regenerative medicine in numerous specialties (including orthopedics, sports medicine, oral and maxillofacial surgery, gynecology, urology) as a useful option for the therapy of disturbed healing processes and is gaining increasingly broad acceptance in the scientific discussion due to the steadily growing clinical evidence.

Blood preparations are subject to the Transfusion Act, the Ordinance on the Manufacture of Medicinal Products and Active Substances (AMWHV) and the German Medicines Act. The potential of PRP is also recognized in aesthetic dermatology. Today, it is used, among other things, in the treatment of disfiguring scar and keloid tissue, for the targeted correction of e.g. symptoms of unnatural skin aging in the face, neck, décolleté and hand areas (“anti-aging”), but also for the treatment of disturbing melasma, stretch marks and distressing alopecia [1-8].

In Switzerland, PRP is used in accordance with Article (9) para. (2)(e) is classified as a “nonstandard drug.” In principle, there is an approval requirement for the manufacture of these. Under certain conditions, which must be cumulatively fulfilled**, PRP may also be produced without Swissmedic authorization; in any case, patients must be informed in advance and their consent obtained (preferably in writing).

** www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/de/home/news/mitteilungen/ new_medicines_legislation_classification_patient_specific_preparations.html (accessed July 20, 2023).

In Germany, PRP is, from a regulatory point of view, a drug that does not require a manufacturing authorization within the meaning of Section 2 (2) of the German Medicines Act. 1 AMG. PRP is furthermore a blood preparation in the sense of § 4 para. 2 AMG or a blood product within the meaning of § 2 Transfusion Act (TFG). However, its production is subject to notification to the appropriate district government.

Looking at the systems for PRP production on the market, the variety of production techniques and protocols is striking. It is obvious that the PRP preparations based on this also have different cell profiles – and thus in principle also different therapeutic potentials.

In some manufacturing techniques, the composition of the cell profile contained in the PRP additionally varies unsystematically depending on operator skill. However, to obtain reliably reproducible PRP qualities, the technique used must be designed in such a way that the result is as independent as possible of the situational skill of the user.

In the absence of a binding nomenclature for characterizing a particular “platelet-rich plasma”, it may happen that independent clinical investigations are performed on the basis of different PRP’s, and when comparing results – occasionally also in scientifically conducted dialogues – unintentionally “apples are compared with oranges and erroneous conclusions are drawn”. Therefore, basic physicians and scientists regularly call for even greater attention to be paid to the standardization of nomenclature, manufacturing processes, and application systems, the reduction of possible sources of error, and the correct selection of the respective PRP preparation for clinical use [9].

What is PRP?

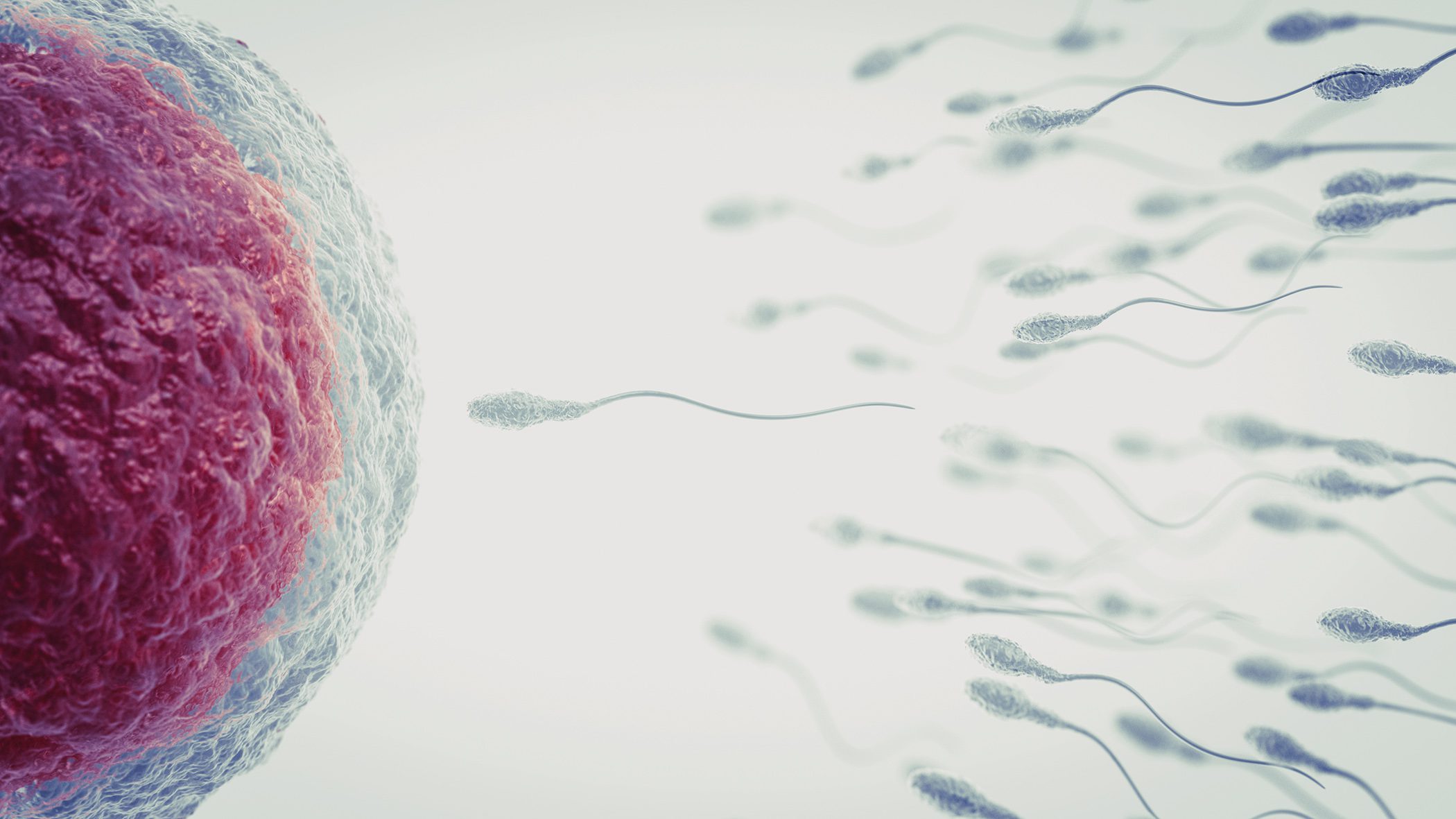

“Platelet-Rich Plasma” (PRP, platelet-rich plasma), is obtained from the patient’s whole blood primarily by centrifugation. Ideally, it consists of blood plasma with an increased concentration of platelets compared to the initial situation.

This fluid is rich in plasma proteins and in growth factors released by platelets – biologically active substances that have a potentially anabolic effect. Autologously reinjected, PRP can interact with the environment at the site of application to naturally stimulate and enhance weakened or impaired regenerative and healing processes of the body. Accelerated tissue healing, improved cell regeneration and an increase in collagen production are the result.

In aesthetic medicine, in addition to the quality of the PRP (including cell profile, plasma volume, reproducibility), the application technique and the number of injections or sessions play a particularly important role.

How is PRP produced?

All systems on the market for PRP production use a centrifuge to spatially separate the blood components. After blood centrifugation, the blood plasma (≈ 55 vol%) is above the corpuscular blood components of erythrocytes (≈ 43 vol%), leukocytes, and platelets (∑ ≈ 2 vol%).

While the erythrocytes (ECs) are clearly separated due to the density ratios, the remaining particles are located in a narrow, intrinsically stratified fringe – the “buffy coat” – lying on top of the ECs. This includes all types of leukocytes (LZ, consisting of monocytes, lymphocytes and granulocytes) and the platelets (TZ), each in all stages of development.

For high-quality PRP, it is useful to irreversibly separate platelets together with plasma as quantitatively and as purely as possible from the other blood components, especially the proinflammatory neutrophil granulocytes (≈ 62 vol% of LC), and to concentrate them moderately [10] – without compromising cell viability and cell viability.

However, this is difficult because the particle types in the “buffy coat” can only be separated from each other with great effort, among other things because of the almost identical density values. Manual aspiration requires a high degree of skill. In addition, there is a high risk of contamination due to the open system, so this method should be considered obsolete.

Many manufacturers use various mechanical or mechano-optical separation methods which, after centrifugation, are intended to separate the buffy coat together with the plasma from the other blood components in a kind of intermediate step. Thereby, these methods tend to stop the separation process rather “conservatively” early to reduce excessive contamination by EZ and LZ. Otherwise, there is a risk that a nominally high TC recovery will also transfer a high proportion of antagonistically acting granulocytes into the PRP – the net therapeutic effect of such PRPs thus often turns out to be low.

The use of an anticoagulant ensures that the blood plasma does not degenerate into serum due to the onset of coagulation processes – important if one wants to produce PRP and not a “platelet-rich serum”.

How does PRP work?

The excellent bioregenerative effect of PRP in the treatment of injured tissues, especially those with low intrinsic healing potential, results from the plasma components concentrated in PRP – signaling, active and nutrient substances (including. amino acids, electrolytes, coagulation factors, hormones, carbohydrates, lipids, soluble proteins, trace elements, metabolites, vitamins) – and the anabolic substances released by the platelets after their activation, including cytokines (= proteins that regulate the growth and differentiation of cells; including growth factors and chemokines) and numerous different bioactive protein and non-protein molecules. [11–13]. With this “cocktail” of active ingredients acting on the repair mechanisms, PRP helps not only to neutralize a biochemical milieu altered towards a catabolic metabolic state and to regulate inflammation-driving processes, but also to positively influence cell growth and to promote neocollagenesis.

Is there an ideal PRP preparation method?

What is certain is that there is no “one right” method for PRP production. However, it is possible to rationally formulate central requirements for the properties that a medical device$ for PRP production should have in order to safely and reproducibly obtain PRP quality with standardized high therapeutic potential:

- MDR(Medical Device Regulation) certification with the highest possible risk class (e.g. medical device classes IIb and III); a medical device in these high risk classes meets the highest safety and performance requirements equally with regard to patients, users and third parties.

- the use of a closed system, i.e., no non-sterile operations from blood collection to reinjection of the finished PRP (e.g., lab-in-a-tube design)

- the targeted separation of a highly potent PRP from plasma and platelets – without relevant admixture of therapy success-reducing antagonistic granulocytes

- High error tolerance and independence of the PRP composition (e.g. with regard to cell profile and plasma recovery) from the skill of the user (e.g. physical “forced process” realized by means of separating gel technology) and thus ensuring a high reproducibility of the manufacturing result

- Intuitive and thus easy-to-learn manufacturing protocol or high degree of user-friendliness (“ease-of-use“)

- suitable tube materials (e.g. non-pyrogenic borosilicate glass) and process parameters (e.g. maximum centrifugal acceleration, start-up and braking curves, duration), among others, to preserve platelet viability and vitality

- correct designation of purpose (for PRP production)

- Deposited clinical evidence/study base to justify intended use

$ Medical devices of all types are products for use in/on humans; the main mode of action is non-pharmacological, immunological or metabolic. In contrast, medicinal products are substances or preparations of substances for use in/on humans or animals.

PRP combination therapies – what regulatory pitfalls need to be considered?

Platelet-rich plasma can also serve as a basis for the preparation of further applications, e.g. in combination with hyaluronic acid (HA). Due to its linear structure, variable molecular weights and 3D secondary structures, the highly hygroscopic HA can take on different physicochemical properties and perform multiple functions in the body.

An exogenous hyaluronic acid suitably “designed” for the intended use can also fix the cells contained in the PRP with its 3D network structure – as a homogeneous “bio-matrix” or “biocompatible, resorbable and biochemical scaffolding component” – and, as a highly viscous gel, represent a “diffusion barrier” for the growth factors released by the platelets over a period of up to 10 days. [14]. These are therefore only released at the site where they are to exert their effect, i.e. directly at or in the target area, where there is also an increase in the retention time and thus temporal availability of the growth factors (Fig. 1).

An effective PRP-HA mixture requires not only a suitable PRP, but also a HA that is specifically tailored to the needs. Both components must then be mixed homogeneously in a suitable ratio to each other, such that, on the one hand, the biological necessities are fulfilled and, on the other hand, the viscosity of the mixture allows the use of injection cannulas with the lowest possible diameters (≥30 G). The latter ensures a low level of pain for the patient and a high level of application safety for all application techniques. Such a PRP-HA combination forms a synergistic duo with a low risk of side effects for the treatment of various indications, e.g. skin surface regeneration and mesotherapy. It is used, among other things, where the skin quality and cellular regeneration and the appearance of the face should be promoted in a natural way.

Regulatory pitfalls

In order to turn a potential application method into a therapeutic option that is also regulatory compliant, numerous regulations and guidelines must be met beforehand. Only then is their use permitted in clinical practice, within the limits set by their intended purpose.

Not all practices observed in practice are compliant with the provisions of the EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR, 2017/745/EU), which has been in force since May 2021, and/or adhere to the important guidelines for “Good Working Practice” (“GxP” rules) that have been established to ensure the safety, efficacy and usability of medical devices. Here are a few notes for orientation:

Proper PRP manufacturing requires not only procedural expertise, but also demands the use of appropriate materials. The occasionally observed use of laboratory diagnostic tubes for “PRP preparation” is prohibited. These in vitro diagnostic (IVD) devices do not require full biocompatibility testing or clinical evaluation – therefore they are not approved for the return to the body of substances obtained with them!

When combining existing (CE-certified) medical devices with each other, or one or more of these with one or more non-medical device(s), there is always a legal presumption under the MDR that this is an in-house manufacture of a medical device – with all the associated legal consequences (e.g. fulfillment and proof of all safety and quality-related requirements, liability risk).

This is even more true when:

- this combination was not intended by the manufacturer of one of the medical devices used, i.e. it is not used in its sense, and

- the components are not used in accordance with their original purpose.

In this situation, the physician is thus potentially considered a “medical device manufacturer” and is then not only obliged to provide complete documentation that is always up to date, including the validated manufacturing process (“instruction manual”, “IFU”), the performance data, the intended purpose, the experience gained from clinical use and much more. The (insurance) risk or legal liability also lies with the (in-house) manufacturer.

Caveat: However, the hyaluronic acid should not be added by the user to the PRP in a second manufacturing step as an “extra” (“open system”); it is also not recommended to apply HA and PRP separately (“one after the other”), since the mixing ratio required for a synergistic effect, but also the equally necessary homogeneous mixing of both components, cannot be guaranteed. Rather, the preparation of the mixture – meeting regulatory requirements and complying with GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) rules – should take place in a closed system with hyaluronic acid presented in a controlled manner as part of the medical device, ideally to combine a standardized PRP in an equally standardized controlled manner.

It becomes clear that in order to turn a potential therapy option into one that is also regulatory compliant, numerous regulations and guidelines must be met. Only then is their use approved in clinical practice.

Currently, the safest method to produce a ready-to-use PRP-HA combination is realized by means of a lab-in-a-tube concept(“CELLULAR MATRIX®” , RegenLab, Fig. 2).

The certified medical device meets the requirements for a medical device of risk class III; for this purpose, a comprehensive clinical evaluation based on clinical data had to be carried out beforehand and the safety and performance as well as the clinical benefit of the device had to be systematically proven. This evidence must be proactively updated annually based on close PMS (Post-Market Surveillance) and PMCF(Post-Market Clinical Follow-up) studies and documented in a CER (Clinical Evaluation Report).

Why anticoagulate during PRP preparation?

In some medical devices for the preparation of PRP, the blood is anticoagulated with an Na3 citrate solution placed in the centrifuge tube – as is the state of the art, for example, in the continuous procedures of intermittent dialysis with regional anticoagulation.

Caution: Subsequent addition of an anticoagulant violates the requirements for a “closed system” for PRP production (including insufficient sterility barrier); in addition, there are risks of incorrect dosing, among others.

If one considers the equation “plasma = serum + fibrinogen”, the necessity of avoiding a coagulation process in PRP production immediately becomes clear: Due to the consumption of e.g. fibrinogen in the course of coagulation, in the worst case only an “apparent PRP” in the form of a non-physiological “platelet-rich serum”, PRS = PRP -(coagulation factors + fibrinogen) would be obtained instead of a “real” PRP.

However, it is not only the concentration of fibrinogen, which is so important for the regenerative potential in PRP, that is reduced. At the same time, for the coagulation process and fibrin polymer formation, proteins are unwantedly and irreversibly consumed already in the centrifuge tube, which also play a key role in promoting regenerative processes – such as cell migration and new cell formation. Consequently, the therapeutic effect of such a “PRP” depleted of active components is always suboptimal.

Last but not least, the use of Na3 citrate in PRP preparation provides a short time buffer compared to non-anticoagulant preparation concepts, which potentially additionally relieves the real day-to-day practice.

With exact adjustment of concentration and volume, the pH value in the PRP remains in the physiological range, which means that a burning stimulus triggered by this in the injection area can be virtually ruled out. If skin reactions such as “burning”, “itching”, “swelling” or “redness” occur in connection with PRP application, these are most likely understandable natural mild and passive reactions of the skin to the injection injury. Many patients find the treatment less painful when performed using a less traumatic “blunt cannula.” This is also considered safer, as its use makes piercing of vessels and nerves much less likely.

In clinical practice, a decreasing sensitivity can usually be observed in the respective subsequent sessions – a possible effect of an increase in skin thickness as a consequence of the previously PRP-induced collagen formation.

Take-Home Messages

- Currently, a variety of PRP manufacturing techniques compete in the market. The medical devices used should be CE marked and comply with the MDR to ensure the safety, efficacy and quality of PRP therapy.

- A highly standardized manufacturing process technology, independent of user skill, enables platelet-rich plasma to be produced consistently and with reproducibly high quality. In combination with evidence-based application protocols and careful application techniques, clinical results and statements with a high level of confidence and evidence can be realized.

- With these “standards” of quality assurance, physicians and patients can benefit from reliable and high-quality treatment, and confidence in the innovative therapy option PRP is strengthened in the long term.

Literature:

- Ahmed NA, Mostafa OM: Comparative study between: carboxytherapy, platelet-rich plasma, and tripolar radiofrequency, their efficacy and tolerability in striae distensae. J Cosmet Dermatol 2018; doi: 10.1111/jocd.12685.

- Alam M, Hughart R, Champlain A, et al: Effect of platelet-rich plasma injection for rejuvenation of photoaged facial skin: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154(12): 1447-1452.

- Cayırlı M, Calışkan E, Açıkgöz G, et al: Regression of melasma with platelet-rich plasma treatment. Ann Dermatol 2014; 26(3): 401-402.

- Cameli N, Mariano M, Cordone I, et al: Autologous pure platelet-rich plasma dermal injections for facial skin rejuvenation: clinical, instrumental, and flow cytometry assessment. Dermatol Surg 2017; 43(6): 826-835.

- Ibrahim ZA, El-Tatawy RA, El-Samongy MA, et al: Comparison between the efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma vs. microdermabrasion in the treatment of striae distensae: clinical and histopathological study. J Cosmet Dermatol 2015; 14(4): 336-346.

- Jiménez Gómez N, Pino Castresana A, Segurado Miravalles G, et al: Autologous platelet-rich gel for facial rejuvenation and wrinkle amelioration: A pilot study. J Cosmet Dermatol 2019; 18(5): 1353-1360.

- Mehryan P, Zartab H, Rajabi A, et al: Assessment of efficacy of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on infraorbital dark circles and crow’s feet wrinkles. J Cosmet Dermatol 2014; 13(1): 72-78.

- Gentile P, Cole JP, Cole MA, et al: Evaluation of not-activated and activated PRP in hair loss treatment: Role of growth factor and cytokine concentrations obtained by different collection systems. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18(2): 408.

- Chahla J, Cinque ME, Piuzzi NS, et al: A call for standardization in platelet-rich plasma preparation protocols and composition reporting: A systematic review of the clinical orthopaedic literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017; 99(20): 1769-1779.

- Atashi F, Jaconi ME, Pittet-Cuénod B, et al: Autologous platelet-rich plasma: a biological supplement to enhance adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2015; 21(3): 253-262.

- Everts PA, Knape JT, Weibrich G, et al: Platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel: a review. J Extra Corpor Technol 2006; 38(2): 174-187.

- Coppinger JA, Cagney G, Toomey S, et al: Characterization of the proteins released from activated platelets leads to localization of novel platelet proteins in human atherosclerotic lesions. Blood 2004; 103(6): 2096-2104.

- Reed GL, Fitzgerald ML, Polgár J: Molecular mechanisms of platelet exocytosis: insights into the “secrete” life of thrombocytes. Blood 2000; 96(10): 3334-3342.

- Atashi F, Jaconi ME, Pittet-Cuénod B, et al: Autologous platelet-rich plasma: a biological supplement to enhance adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2015; 21(3): 253-262.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2023; 33(4): 6-10