An afternoon event on “Neuro Emergencies” at the Inselspital in Bern focused, among other things, on the clinical distinction between psychogenic and epileptic seizures. The two types of seizures have a varied, often similar clinical presentation. Differentiation is important precisely because of the different therapies. Furthermore, the treatment of confusional states in the elderly was the focus of interest.

Paroxysmal events often present with pain, impaired consciousness, dizziness, paralysis, and loss of tone. Because most phenomena can be observed in both psychogenic and epileptic seizures, clinical differentiation is often difficult in individual cases. However, such a diagnosis is necessary: “Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNEPE) are a disease that requires therapy and not a diagnosis of exclusion,” says Prof. Mathias Sturzenegger, M.D., chief physician at the University Clinic for Neurology, Bern. An essential tool for clinically distinguishing an epileptic-related event (EPE) from a nonepileptic-related paroxysmal event (NEPE) is an accurate history, including extraneous history. NEPE occur physiologically, for example as myoclonia of falling asleep, pathologically in TIAs or syncope, and psychogenically (PNEPE). “Differentially, seizures with loss of consciousness must always be thought of as convulsive syncope,” Prof. Sturzenegger said.

An important distinguishing feature between NEPE and EPE is the sequence of events: for example, the loss of consciousness and muscle atonia in syncope occur before the convulsions. In addition to motor symptoms, the eyes are an important tool for distinguishing convulsive syncope from grand mal and psychogenic vs. epileptic seizure. These are usually open during an epileptic seizure. Inferences can also be drawn from skin color and observation of how the patient recovers from the event and whether they remember it.

An epileptic seizure results from nonspecific stimuli or damage to the brain. “Basically, anyone can have an epileptic seizure,” Prof. Sturzenegger said. However, one speaks of epilepsy only when repeated, mostly spontaneous seizures occur and when abnormal electrical activity has been detected in the affected person. It is also often difficult to distinguish PNEPE because it can also be convulsive. PNEPE are observed ostensibly in young adults – primarily women. Anamnestically, a psychological and psychiatric previous burden is often found. Helpful for the distinction are references to conflict situations as triggers. Often the seizures occur while awake and in the presence of witnesses. The lack of stereotypy in multiple or well-described seizures is striking. In addition, the long seizure duration (>2 minutes) in PNEPE, the goal-directed movements that can be influenced by the examiner, and the preserved consciousness, which is often accompanied by crying, provide valuable clues. In case of doubt, video telemetry should be used for reliable delineation.

Confusion in the elderly: Haloperidol acute and quetiapine in long-term treatment.

Impaired consciousness in the elderly typically develops in a short period of time and is medically justifiable.

Substance intoxications, side effects or drug interactions, or lack of fluids are common causes of confusional states in the elderly. In addition to impaired consciousness, psychomotor abnormalities such as hyperactivity and hypoactivity as well as cognitive and emotional changes are observed. The number of differential diagnoses is high, ranging from infections to acute cerebral events such as hemorrhage or stroke. In addition to general risk factors such as age, the risk increases with pre-existing conditions such as dementia and substance-related dependence, but especially with the number of medications taken, particularly psychotropic drugs, prior to hospitalization.

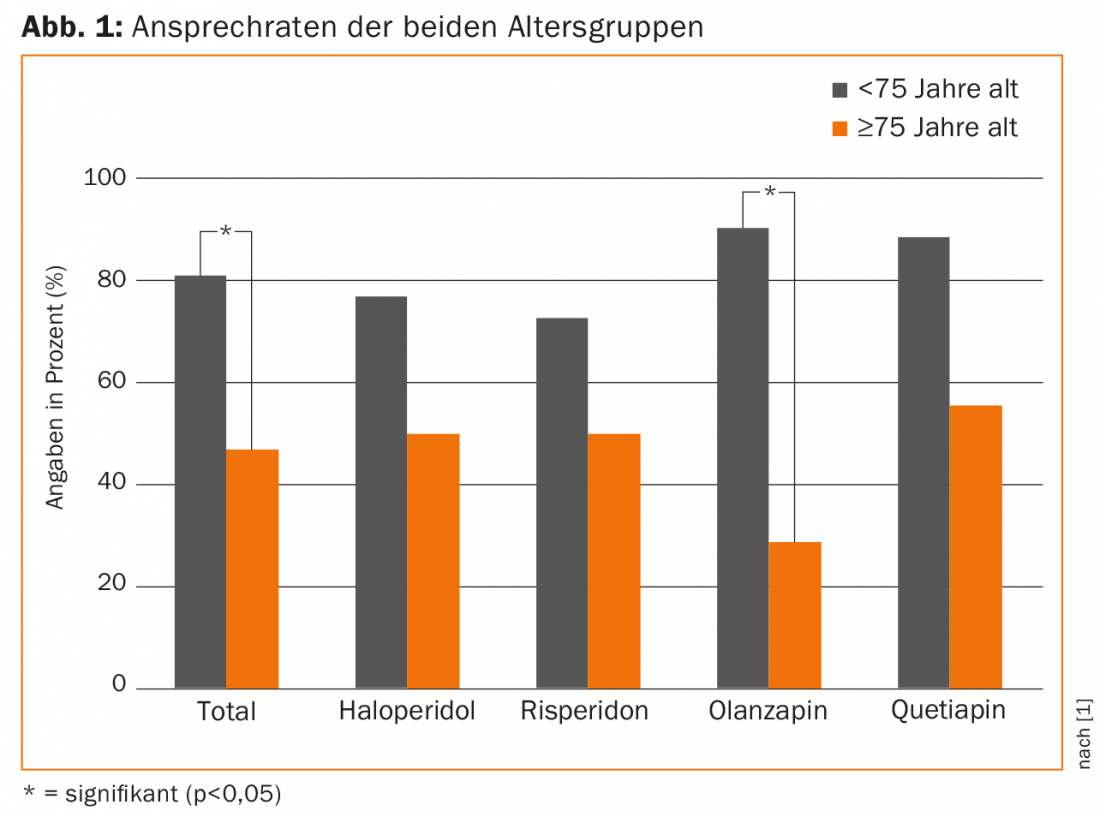

Delirium and confusional states in the elderly are poorly studied. Similar issues apply to drug trials with psychiatric patients because of ethical problems in conducting them. “When prescribing psychotropic drugs, we often move in the off-label area,” noted Prof. Thomas Müller, M.D., chief physician and deputy chief medical officer. Director, University Hospital and Polyclinic for Psychiatry, Bern. He referred to a recent Korean observational study that compared the efficacy and safety of haloperidol with the atypical antipsychotics risperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine for the treatment of delirium in elderly patients [1]. Patients were treated with a flexible dosing regimen for six days depending on clinical symptoms. “Crucially, the groups did not differ in terms of chlorpromazine equivalents,” Prof. Müller said. In total, about one-tenth of the dose needed to treat acute psychosis was used.

As the study showed, there was a significant decrease in delirious symptomatology under all medications. Differences, on the other hand, were observed in responsiveness. Thus, the psychotropic drugs studied resulted in a better effect in patients <75 years of age than in older sufferers. The highest response rate in >75-year-olds was shown with quetiapine (Fig. 1) . Regarding safety, there were no significant differences between the substances. According to the trend, the fewest side effects were observed with quetiapine. “Quetiapine seems to be a fairly safe drug in old age and is popular for that reason,” Prof. Müller said.

As for psychopharmacological intervention in the elderly, the psychiatrist recommended avoiding anticholinergic substances because the brain is more susceptible to the side effects of these substances with age. Tricyclic antidepressants and, because of their cumulative effect, long-acting sedatives can cause confusion and should also be avoided. For the changeover, the specialist recommended a sequential rather than a parallel approach. Basically, “Haloperidol is helpful in acute situations and quetiapine for long-term therapy.”

Source: Interdisciplinary Symposium Neuro Emergencies, May 28, 2015, Bern.

Literature:

- Yoon HJ, et al: Efficacy and safety of haloperidol versus atypical antipsychotic medications in the treatment of delirium. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13: 240.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(4): 32-33.