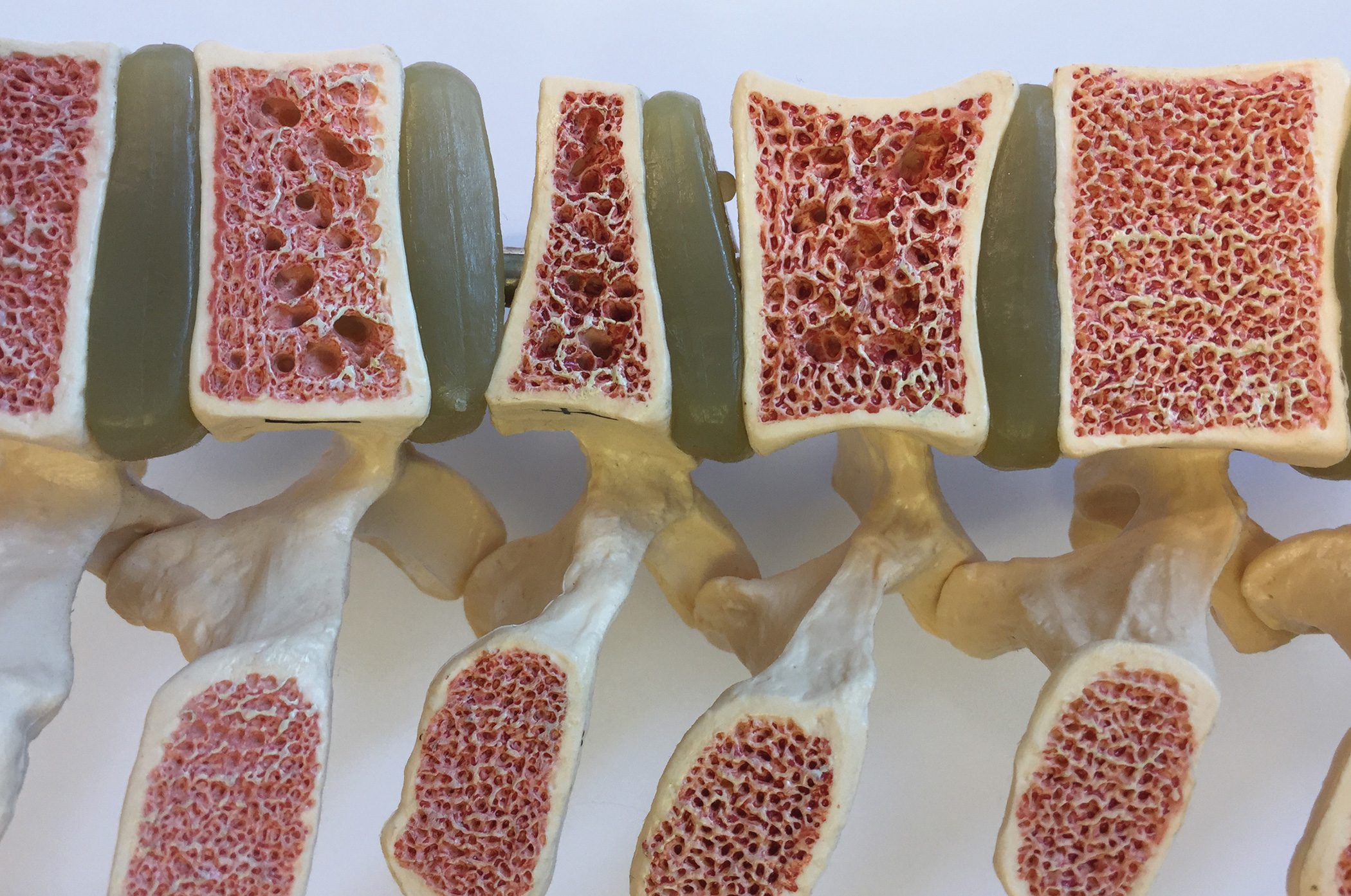

Spondylosis hyperostotica is the most common non-inflammatory disease of the spine, with an age-correlated increase in prevalence. This degenerative spinal disease occurs more frequently in patients with diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. The characteristic hyperostoses on the anterior and lateral surfaces of the vertebral bodies are an image morphological diagnostic feature. There are a few things to keep in mind when examining by CT, MRI or X-ray.

In addition to age-related degenerative changes of the skeletal system, overload can have an influence on osteoligamentous and cartilaginous changes. When the balance between loading and unloading is disturbed, mucoid degeneration and coagulation necrosis occur in the fibrocartilage zone of the tendon and ligament attachments [4,12]. Reactive fibroostosis, caused by formation of osteophytes in the insertion area of the ligaments and tendons, leads to reattachment of the insertion from within the bone. Systemically, these reactions can occur in various regions of the human skeletal and articular system when hormonal stimulation causes cartilage to proliferate. A well-known example is acromegaly, which leads to excessive growth on the acra.

Substantial fibroostoses are also found in diseases with osteoplastic diathesis, such as spondylosis hyperostotica or diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, DISH syndrome. Idiopathic pachydermoperiostosis [6] and chronic endemic or industrial fluorosis are also included in this group.

Numerous terms describing these skeletal changes can be found in the literature (overview 1).

The fibroostoses can become clinically relevant when they cause a mechanical stimulus on adjacent soft tissue structures such as skin and subcutaneous tissue or, in the area of the joints, on bursae by expansion and pressure, which then leads to the local inflammatory and pain reaction up to the restriction of movement and stress. An example found in daily practice is the plantar or also dorsal heel spur. Similarly, hyperostoses may mimic tumorous findings when peripherally located, such as sternoclavicular hyperostosis in the upper thoracic aperture [3]. Vascular alterations are also possible and hypertrophic spondylosis of the cervical spine may provoke dysphagia [7].

DISH syndrome is usually found in older patients, is relatively common, and can be documented radiographically with calcifications and ossifications of ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules [8,11,13]. Patients are particularly likely to be affected by obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hyperuricemia, and diabetes mellitus. The risk of cardiovascular disease is increased. Skeletal hyperostosis may also be part of the changes in syndromes [9], such as SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis).

In spinal manifestation, the right ventrolateral region of the spine is very commonly affected with hypertrophic spondylosis. Depending on the extent of the hyperostoses, neck or back pain, restricted mobility and general weakness may occur [5]. X-rays of the spine in two planes can already demonstrate the skeletal changes, often offering the “candle wax image”. However, in addition to ventrolateral spondylosis, hypertrophic retrospondylosis may also affect clinical symptoms with medullary and radicular impressions [4]. Similarly, space-occupying ossifications of the posterior longitudinal ligament are the cause of spinal stenosis and medullary alteration [10].

Computed tomography can be used to map the exact extent of hypertrophic spondylosis in the axial scans [10], supplemented by multiplanar reconstructions. The bony foraminal or spinal stenosis can be measured more accurately than in MRI. Intravenous administration of contrast does not provide diagnostic benefits.

Magnetic reson ance imaging studies can primarily use sagittal measurements to visualize hypertrophic and synostosing spondylosis. Differentiation from inflammatory osteopathy is achieved with fat-suppressive native and contrast-assisted sequences.

Case studies

Case 1 (Fig. 1A and B) shows advanced degeneration of cervical spine segments and mild form of hypertrophic spondylosis deformans and osteochondrosis in a 77-year-old patient with neck pain and markedly limited mobility of the cervical spine in all directions of motion in the 2D reconstructions of a cervical multislice CT.

Case 2 (Fig. 2A through D) documents diffuse hypertrophic spondylophytic changes of the cervical spine (radiograph, MRI) and radiographically also of the lumbar spine in a 79-year-old patient. Clinically, there was a pronounced neck-shoulder-arm syndrome as well as a lumbar syndrome. In particular, the mobility of the cervical spine was dramatically limited. A detailed rheumatological check-up ruled out ankylosing spondylitis in both cases, and the rheumatoid factors and inflammatory parameters were unremarkable.

Take-Home Messages

- Hypertrophic spondylosis deformans is an alteration of the spine in the elderly.

- In addition to spondylosis hyperostotica, reactive hypertrophic bone changes can also occur in other skeletal regions, collectively known as disseminated idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH).

- Metabolic and hormonal disorders may influence excess bone growth.

- A typical laboratory chemical change is not detectable in hypertrophic spondylopathy.

- Imaging evidence is primary with x-rays in 2 planes, CT can determine the extent of any resulting stenosis of the neuroforamina or spinal canal, and MRI can visualize accompanying inflammatory changes, radicular or medullary stimuli.

Literature:

- Aydin E, et al: Six casas of Forestiers syndrome, a rare cause of dysphagia. Acta Otolaryngol 2006; 126(7): 775-778.

- Cholankeril JV, et al: Diffuse posterior hyperostosis of the cervical spine with cord compression: a Forestier (DISH) variant. J Comput Tomogr 1983; 7(2): 171-174.

- Farrès MT, Grabenwöger F: The sternoclavicular hyperostosis: space-occupying lesion of the upper thoracic aperture. Radiologist 1988; 28: 584-587.

- Frommhold W, et al. (Ed.): Schinz Radiological Diagnostics in Clinic and Practice. 7th revised edition. Volume IV – Part 1: Bone-joints-soft tissues I. Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, New York; 1989, 904-911.

- Ghosh B, et al: Diffuse interstitial skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) in type 2 diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India 2004; 52: 994-996.

- Kreitner KF, Eckardt A, Schild HH: Radiographic findings in primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (pachydermoperiostosis). Act. Radiol 1995; 5: 106-108.

- Kritzer RO, Rose JE: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis presenting with thoracic outlet syndrome and dysphagia. Neurosurgery 1988; 22(6 Pt 1): 1071-1074.

- Mader R, et al: Extraspinal manifestations of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. Rheumatology 2009; 48(12): 1478-1481.

- Mulleman D, et al: Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine and SAPHO syndrome. J Rheumatol 2005; 32(7): 1361-1364.

- Razmi R, Khong KS: Cervical cord injury in an elderly man with a fused spine – a case report. Singapore Med J 2001; 42(10): 477-481.

- Resnick D, Shaul SR, Robins JM: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH): Forestier’s disease with extraspinal manifestations. Radiology 1975; 115(3): 513-524.

- Thiel HJ: Cross-sectional diagnosis of the spine (1.12). Degenerative changes: Spondylosis hyperostotica. MTA Dialog 2012; 5(13): 444-447.

- Vezyroglou G, Mitropoulos A, Antoniadis C: A metabolic syndrome in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. A controlled study. J Rheumatol 1996; 23(4): 672-676.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(11): 48-50