Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a chronic, progressive liver disease that usually affects women in the second half of life. It is often an incidental finding, especially as more than half of the cases are asymptomatic. If alkaline phosphatase and/or gammaGT are elevated, the diagnosis can be confirmed by determining anti-mitochondrial antibodies. In addition to disease-modifying treatment, symptom management is also important.

At the annual congress of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), Dr. Jess Dyson, consultant hepatologist at the Freeman Hospital in Newcastle (UK) and head of the clinical service for patients with autoimmune liver disease, spoke about the current status and challenges associated with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) [1]. PBC is an autoimmune liver disease that affects the biliary epithelial cells within the liver. During the course of the disease, the microscopic bile ducts within the liver are destroyed, resulting in reduced bile flow or bile stasis [2]. This can lead to progressive liver scarring and ultimately to liver cirrhosis [1]. According to Dr. Dyson, the most important predictor of long-term outcomes is the extent to which liver values improve under drug treatment [1].

Antibody detection central, liver biopsy usually obsolete

Itching, fatigue and dry mouth and eyes are the most common initial symptoms and often develop gradually. In asymptomatic patients, PBC is diagnosed by chance when abnormalities such as an increase in alkaline phosphatase (AP) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) are detected [3]. The combination of positive anti-mitochondrial or PBC-specific antinuclear antibodies with elevated AP has over 95% specificity and sensitivity for the diagnosis of PBC, according to Dr. Dyson [1]. Disease-specific anti-mitochondrial antibodies are found in >90% of patients with PBC, but in less than 1% of healthy controls, and are only absent in <5% of PBC patients [4–6].

| The causes of PBC are not yet fully understood, explained Dr. Dyson, who co-authored the British guideline for PBC, primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis. According to current knowledge, there are genetic and environmental risk factors. Around 90% of PBC patients are female. It is not known why men only make up a small minority of patients. It may have something to do with hormonal factors, particularly oestrogen. One risk factor that has been identified in some studies is recurrent urinary tract infection, which often affects women. The majority of patients, but not all, are over 60 years old at the time of diagnosis. In patients under 45 years of age, the risk of a poor response to therapy and the need for a liver transplant is increased. |

| according to [1] |

In clinically suspected PBC without detection of anti-mitochondrial antibodies, PBC-specific ANA should be tested for by immunofluorescence testing on HEp2 cells that show a specific nuclear dot pattern or ring-shaped nuclear fluorescence [7]. The target antigens of PBC-specific ANA have been identified as sp100 and gp210, which can be tested by ELISA [8–11]. Serum bilirubin is usually within the normal range in early stages; an increase in bilirubin indicates disease progression and worsening of the prognosis [3]. Liver biopsy is no longer part of routine diagnostics unless there is a suspected overlap with autoimmune hepatitis [1].

Ursodiol as first-line therapy is effective in many cases

Currently available drugs can slow down the liver damage and sometimes bring it to a halt. The first-line treatment for PBC is ursodeoxycholic acid (synonym: ursodiol) at a dosage of 13-15 mg/kg body weight/day. This litholytic agent reduces the amount of toxic bile acids and stimulates bile flow by substituting the toxic bile acid with the hydrophilic, cell-protective and atoxic ursodeoxycholic acid. At therapeutic doses, it is a very effective therapy for many patients, improving long-term clinical outcomes and liver transplant-free survival. This has been demonstrated in several placebo-controlled studies and long-term observations [12,13].

| Aiming to improve quality of life While therapy studies have traditionally focused on improvements in liver values in the blood, clinicians and researchers have now recognized the importance of quality of life [1]. In this context, PPAR ligands (Table 1) have attracted considerable interest, as clinical studies have shown a reduction in itching as a secondary endpoint, as measured by NRS**, VAS$ or VRS& [18]. After treatment with Seladelpar over a period of one year, sleep disorders and fatigue also improved [19]. |

| ** NRS = numerical rating scale $VAS= visual analog scale &VRS= verbal rating scale |

It is recommended to initiate treatment with ursodiol as soon as possible after diagnosis, as delayed initiation of therapy may have unfavorable effects. A subpopulation of PBC patients do not show a complete response to ursodiol. Risk stratification to identify these patients is key, Dr. Dyson emphasized [1]. The PBC Global Study Group was able to show that patients who had bilirubin below 1.0 mg/dL and AP below twice the upper normal value one year after starting ursodiol therapy had the best prognosis in terms of liver transplant-free survival and overall survival [14]. The Global PBC score is composed of age, AP, bilirubin, platelet count and albumin and can be calculated online to estimate individual risk [4,14]: www.globalpbc.com

What second-line therapies are available?

Obeticholic acid is available as an alternative treatment option for patients who do not respond adequately to ursodiol or who cannot tolerate it. Obeticholic acid is an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), which protects the liver from toxic bile acids and stimulates bile flow. Obeticholic acid has been approved in Switzerland since 2018 and can be combined with ursodiol or used as monotherapy [15,16]. Undesirable side effects include itching and elevated cholesterol.

Fibrates can also lead to an improvement in symptoms and liver values in patients for whom treatment with ursodiol is not effective. Fibrates – PPAR-α agonists, which bind to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α – have an anti-cholestatic effect and relieve itching. In Switzerland, fibrates have long been approved for the treatment of elevated blood lipids, but PBCs are used off-label. With second-line therapies, it is important to discuss the expected benefits in relation to the potential risks in a multidisciplinary team and with the patient. In patients with advanced liver cirrhosis, both treatment options can lead to complications. In the EU context, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recently recommended that the conditional marketing authorization for obeticholic acid be revoked [17]. And with fibrates, there is a certain risk of acute liver damage and renal dysfunction, as Dr. Dyson mentioned. Numerous research efforts are currently underway to expand the range of treatments for PBC. In addition to fenofibrate and bezafibrate as representatives of the fibrates, active substances from the non-fibrate group are also being investigated with seladelpar and elafibranor (Table 1).

Congress: EASL Congress 2024

Literature:

- “Rare but not forgotten – The challenges of living with PBC”, Policy dialogues, EASL Congress, Milan, 5-8 June 2024.

- University Hospital Würzburg: Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), www.ukw.de/behandlungszentren/leberzentrum,(last accessed 20.08.2024).

- “Primary biliary cholangitis,” Tae Hoon Lee, MD, %C3%(last accessed Aug. 20, 2024).

- “S2k Guideline Autoimmune Liver Diseases”, AWMF Reg. No. 021-27, https://register.awmf.org,(last accessed 20.08.2024).

- Gershwin ME, et al: Identification and specificity of a cDNA encoding the 70 kd mitochondrial antigen recognized in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Immunol 1987; 138: 3525-3531.

- Oertelt S, et al: A sensitive bead assay for antimitochondrial antibodies: Chipping away at AMA-negative primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2007; 45: 659-665.

- Invernizzi P, et al: Comparison of the clinical features and clinical course of antimitochondrial antibody-positive and -negative primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 1997; 25: 1090-1095.

- Nickowitz RE, Worman HJ: Autoantibodies from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis recognize a restricted region within the cytoplasmic tail of nuclear pore membrane glycoprotein Gp210. J Exp Med 1993; 178: 2237-2242.

- Szostecki C, et al: Isolation and characterization of cDNA encoding a human nuclear antigen predominantly recognized by autoantibodies from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Immunol 1990; 145: 4338-4347.

- Invernizzi P, et al: Antinuclear antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Seminars in liver disease 2005; 25: 298-310.

- Wesierska-Gadek J, et al: Correlation of initial autoantibody profile and clinical outcome in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2006; 43: 1135-1144.

- Poupon RE, Poupon R, Balkau B: Ursodiol for the long-term treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. The UDCA-PBC Study Group. NEJM 1994; 330: 1342-1347.

- Poupon RE, et al: Combined analysis of randomized controlled trials of ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1997; 113: 884-890.

- Lammers WJ, et al: Levels of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin are surrogate end points of outcomes of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: an international follow-up stu dy. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 1338-1349 e5; quiz e15

- Swiss Liver Patients Association, www.swisshepa.org,(last accessed 20.08.2024).

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 20.08.2024).

- Deutsche Leberhilfe e.V., www.leberhilfe.org/pbc-europaeische-arzneimittelagentur-empfiehlt-die-zulassung-von-obeticholsaeure-zu-widerrufen,(last accessed 20.08.2024).

- Colapietro F, Gershwin ME, Lleo A: PPAR agonists for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis: Old and new tales. J Transl Autoimmun 2023 Jan 5; 6:100188. doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2023.100188.

- Kremer AE, et al: Seladelpar improved measures of pruritus, sleep, and fatigue and decreased serum bile acids in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Liver Int 2021 doi: 10.1111/liv.15039.

- Corpechot C: The role of fibrates in primary biliary cholangitis. Curr Hepatol Rep 2019; 18: 107-114.

- Hirschfield GM, et al: A phase 3 trial of seladelpar in primary biliary cholangitis. NEJM 2024; 390(9): 783-794.

- Kowdley KV, et al: Efficacy and safety of elafibranor in primary biliary cholangitis. NEJM 2023; 390: 795-805.

- Guoyun X, et al: Efficacy and safety of fenofibrate add-on therapy in patients with primary biliary cholangitis refractory to ursodeoxycholic acid: a retrospective study and updated meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 2022; 30; 13: 948362.

- Van Hooff MC, et al: Real-world experience with fibrates in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Poster presentation at: The Liver Meeting 2023; November 13, 2023. Boston, MA. Abstract 4569C.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(9): 22-23 (published on 18.9.24, ahead of print)

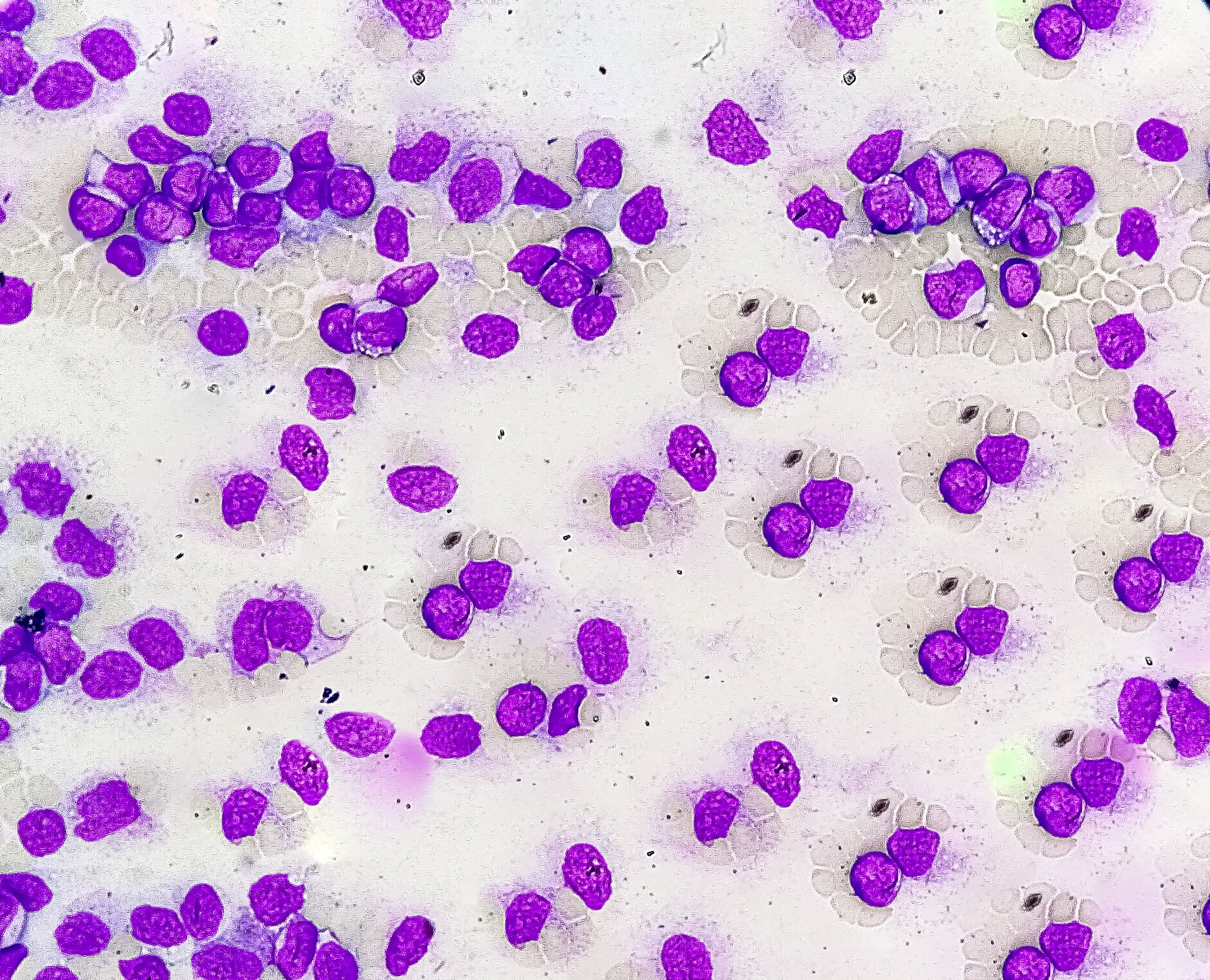

Cover picture: Intermediate magnification micrograph of primary biliary cirrhosis. H&E stain. ©Nephron, wikimedia