Inflammatory spinal changes are most common in older adults. Today, MRI is considered the diagnostic gold standard. In case of contraindications to MRI, multislice CT serves as an alternative. The primary form of spondylodiscitis is caused by the hematogenous spread of pathogenic germs and may also occur as a result of surgical procedures or traumatic events.

About 3% of inflammatory skeletal diseases are localized in the spine with formation of spondylodiscitis. Causes are hematogenous metastases of infectious foci, consequence of surgical complications, drug injections or trauma. Spread per continuitatem from adjacent soft tissue and organ inflammation is also possible. Metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus or weakening of the immune system may favor the spread of infection [1,8]. In addition to a first peak of bone inflammation in childhood with osteomyelitis primarily in the area of the long tubular bones, there is a second peak of the disease in adults beyond the age of 50, then with dominance in the area of the spine [6,7]. In children, spondylodiscitis accounts for only 2% to 4% of inflammatory skeletal changes [10].

The most common pathogens are listed in Table 1. Staphylococcus aureus accounts for more than 50% of non-tuberculous infections [3].

Especially image morphologically, differential diagnostic considerations must be made when spinal inflammatory disease is suspected, as listed in review 1 [7].

Today, numerous antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents are available for the treatment of spondylodiscitis. However, as in the case presented, conservative therapy does not guarantee control of the infection. Surgical intervention remains as a therapeutic option [3].

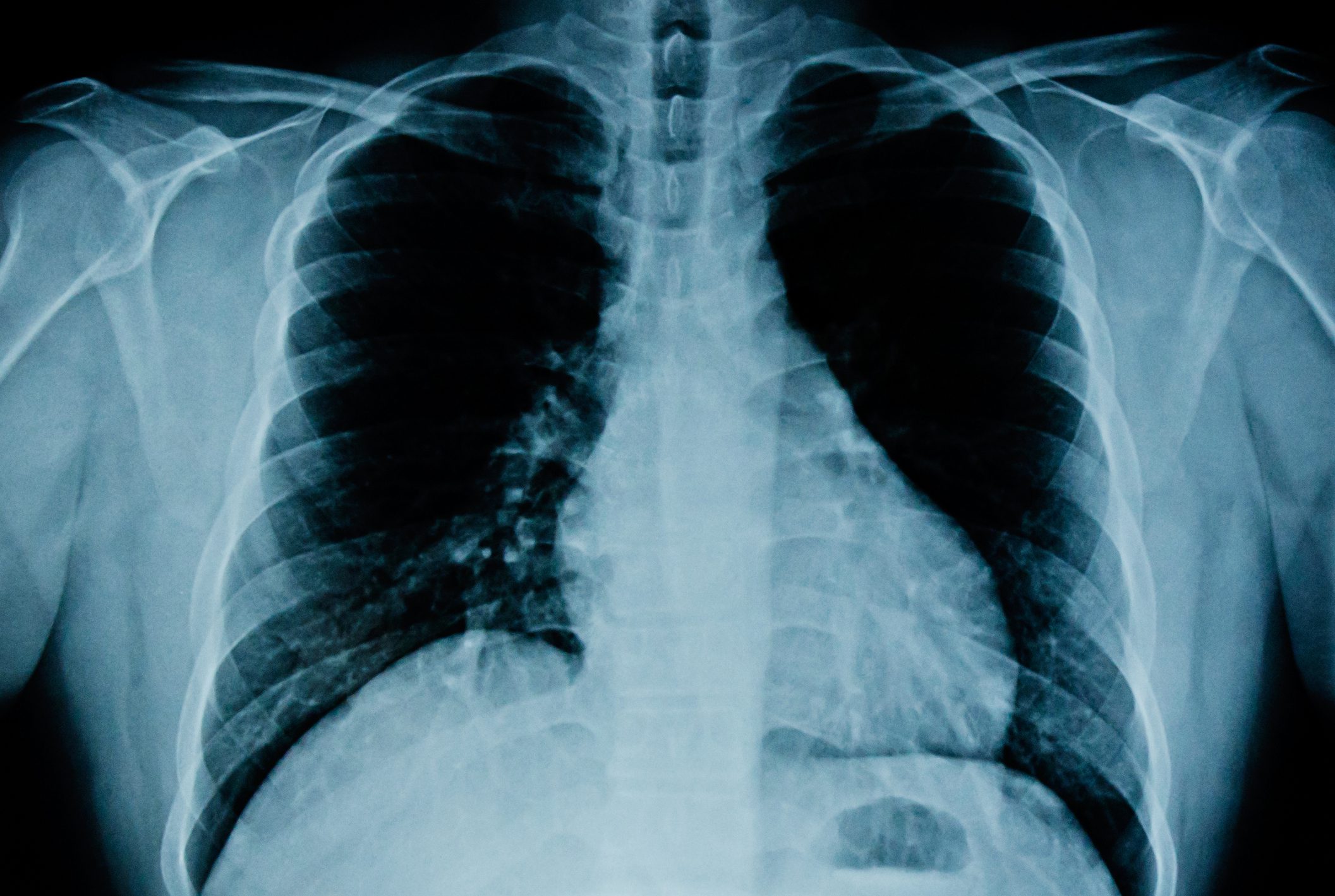

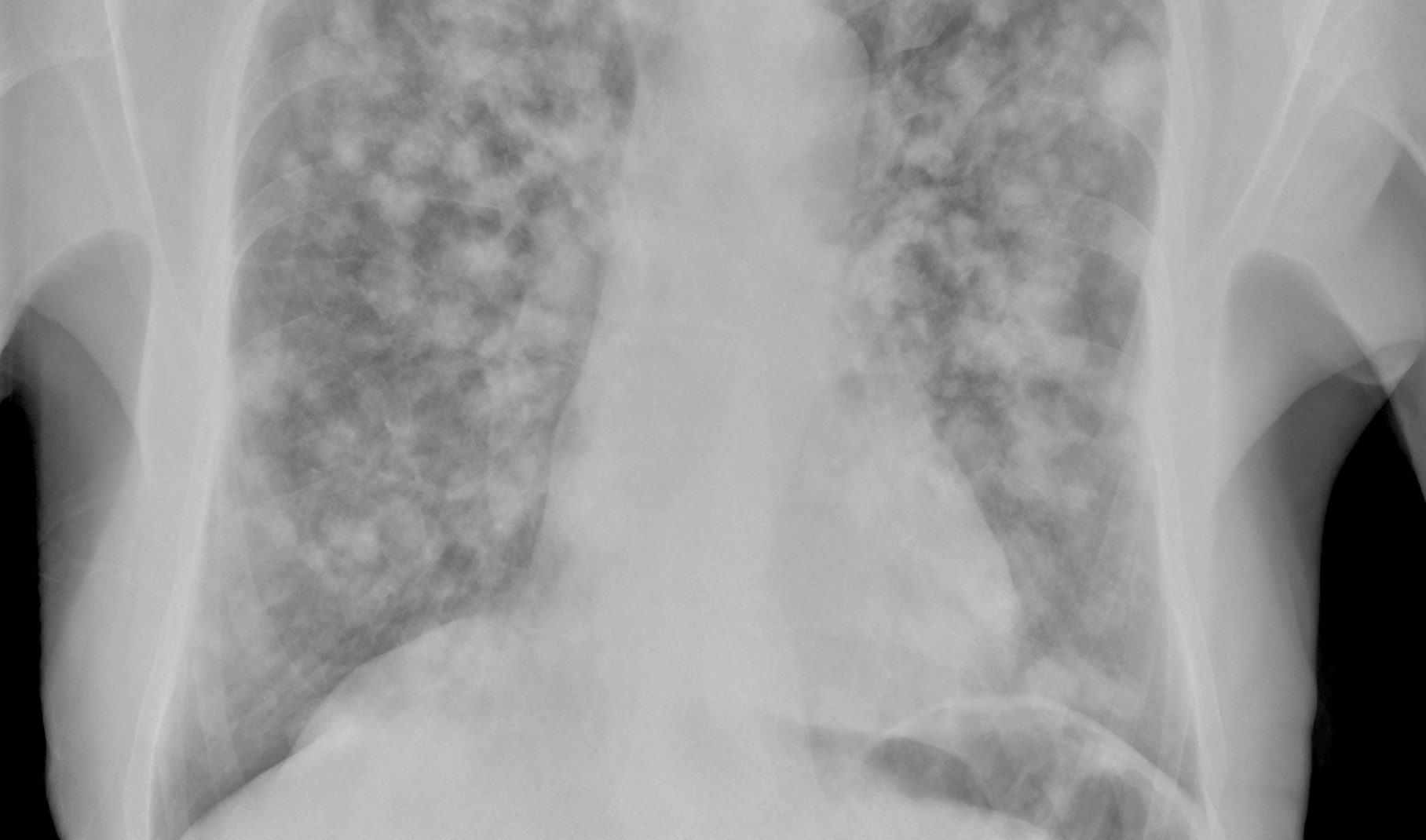

Computed tomographic images have clearly taken a back seat in the context of inflammation diagnostics of the skeletal system after the establishment of magnetic resonance imaging. However, the true extent of bony destruction can be well determined on multi-slice CT. In contraindications to MRI (e.g., pacemaker), active inflammation in contrast series shows veil-like enhancement on CT. If blood cultures obtained for pathogen identification are negative, CT-guided puncture for material collection may be diagnostically useful [2,4,5].

Magnetic resonance imaging examinations offer distinct advantages over other imaging modalities in the diagnosis of inflammation when soft tissue contrast is high. KM-assisted sequences visualize the extent and activity of inflammation very well. If this is seen primarily in the ventral portion of the vertebrae and spread along the anterior longitudinal ligament, this may indicate tuberculous involvement [7]. The signal changes in T1w and T2w as well as in fat suppressive sequences are typical, post intravenous contrast agent application the segmental inflammation of the vertebrae, intervertebral discs and usually also that of the surrounding soft tissues can be accurately detected [9].

Case study

The case documented in the course of a 63-year-old multimorbid patient at diagnosis is quite impressive. The woman was in a reduced general condition and wheelchair dependent after having undergone an apoplexy years ago. There was long-standing insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The husband cared for her, assisted by an ambulatory care service. Since she had slurred speech even after the cerebral insult, the initial symptoms with back pain without radicular radiation, dominantly in the lower lumbar spine, were obviously not noticed in the surrounding area at first. Pain increased and general condition worsened with subfebrile temperatures. MRI requested for clarification revealed evidence of spondylodiscitis in segment L3/4 in multisegmental degenerative disco- and spondyloarthropathy (Fig. 1A to 1D). With prompt initiation of oral antibiotics, symptoms increased, and control MRI 10 days after initial diagnosis also showed marked extension of inflammation (Fig. 2A to 2C). Therapy was then performed neurosurgically.

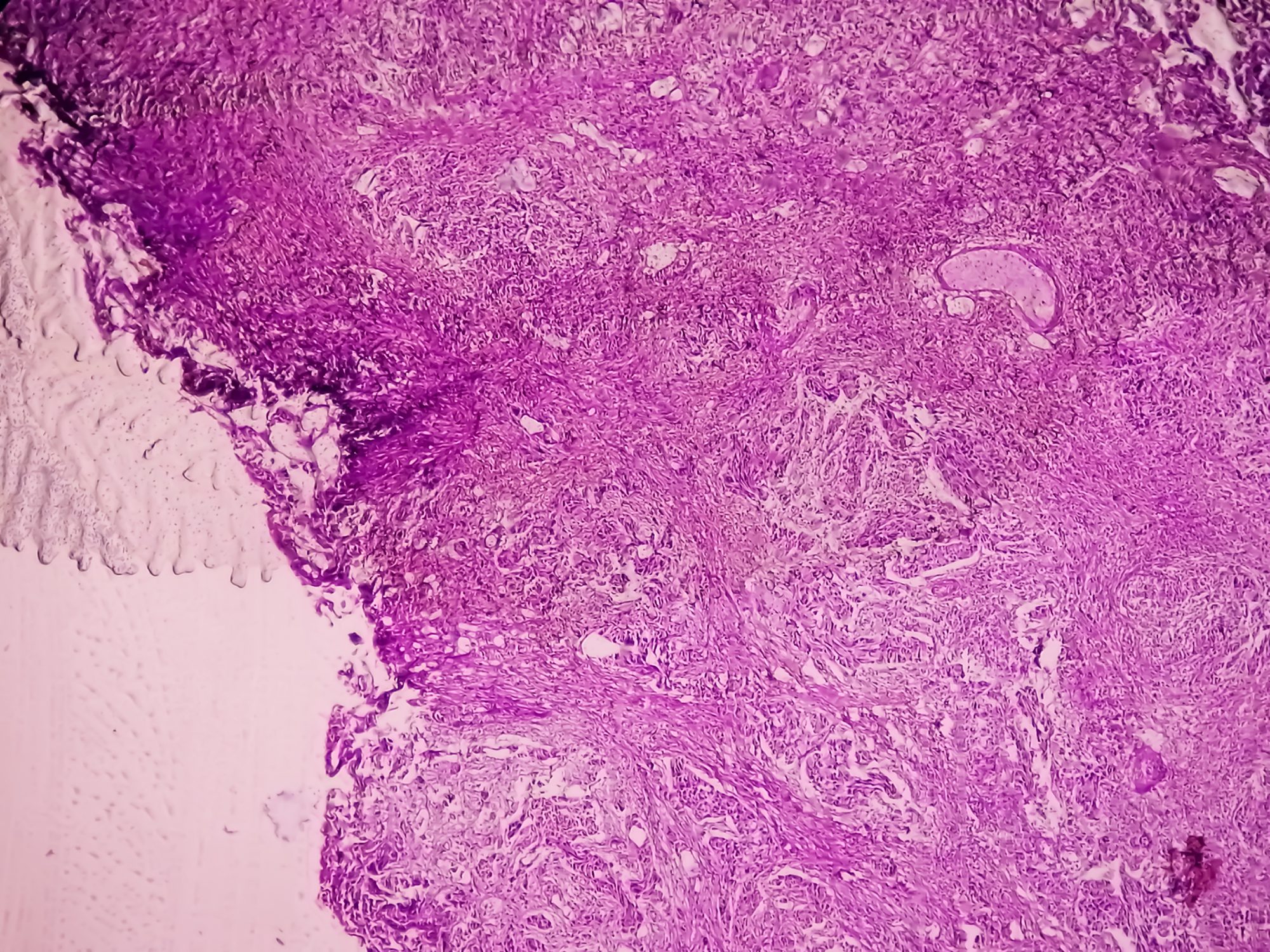

In early 2018, the patient underwent surgical treatment for mammary carcinoma and spondylodesis with internal fixator for intervening spinal sintering and instability (Fig. 3).

Literature:

- Burgener FA, et al: Differential diagnostics in MRI. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York 2002; 322.

- Cottle R, Riordan T: Infectious spondylodiscitis. J Infect 2008, Apr. 26.

- Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM: Spondylodiscitis: Update on Diagnosis and Management. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65 Suppl 3: iii11-24.

- Grumme T, et al: Cerebral and spinal computed tomography. 3rd completely revised and expanded edition. Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag Berlin, Vienna 1998: 258.

- Kauffmann GW, Rau WS, Roeren T, Sartor K, (eds). X-ray Primer. 3rd revised edition. Springer-Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg, New York 2001; 531-532.

- Sartor K (ed.): Neuroradiology. 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York 2001: 316-317.

- Tali ET: Spinal infections. Eur J Radiol 2004; 50(2): 120-133.

- Thiel HJ: Cross-sectional diagnosis of the spine: inflammatory changes (3.1): Spondylodiscitis of the lumbar spine. MTA Dialog 2008; 11(9): 918-920.

- Uhlenbrock D (ed.): MRI of the spine and spinal canal. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York 2001: 360.

- Völker A, Schubert S, Heyde C: Spondylodiscitis in Children and Adolescents. Orthopaedics 2016; 45(6): 491-499.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(10): 46-48