Das vom American College of Rheumatology (ACR) und der European League against Rheumatology (EULAR) gemeinsam entwickelte und 2022 veröffentlichte Update der Klassifikationskriterien für Riesenzellarteriitis trägt insbesondere den Fortschritten im Bereich der Bildgebungsdiagnostik Rechnung und löst die aus den 1990er Jahren stammende frühere Klassifikation ab.

Giant cell arteritis, like Takayasu’s arteritis, is one of the large vessel vasculitides. It affects the vessels originating from the aortic arch and especially the extracranial branches of the carotids. Common symptoms of giant cell arteritis (RZA) include headache, constitutional symptoms, jaw spasms, scalp tenderness, visual disturbances, and elevated inflammatory markers [1]. Prof. Thomas Daikeler, MD, Senior Physician, Rheumatology, University Hospital Basel, provided an update on the diagnosis and treatment of RZA [2]. The nonspecific nature of many RZA-associated symptoms may discourage patients from consulting their primary care physician and lead to misdiagnosis [3]. A recent secondary analysis reported a median diagnostic latency between symptom onset and RZA diagnosis of 9 weeks [3,4]. A mandatory criterion for giant cell arteritis is an age ≥50 years at the time of diagnosis. Additional clinical criteria are weighted with a point system (Table 1) [5]. Cluster analyses of vascular imaging data identified bilateral axillary involvement and increased uptake of 18-FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) on positron emission tomography (PET) of the aorta as specific imaging patterns for RZA.

ACR/EULAR classification criteria for giant cell arteritis

Between January 2011 and December 2017, the DCVAS (“The Diagnostic and Classification Criteria for Vasculitis”) study recruited participants from 136 sites in 32 countries [5]. A total of 942 cases of confirmed giant cell arteritis were available for analysis. Only 7 of 942 patients with RZA were diagnosed at <50 years of age. Therefore, this age-related cut-off was set as the overriding criterion. For subsequent analysis, 756 RZA cases were randomly selected and compared in a counterbalanced fashion with a control group. Following a data-driven expert consensus process, a total of 72 items from the DCVAS case reports were included in the regression analysis.

The evaluation resulted in the following point-weighted ACR/EULAR clinical classification criteria of giant cell arteritis (Table 1) [5]:

- A positive temporal artery (TA) biopsy or TA halo sign on ultrasound (+5).

- An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥50 mm/h or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥10 mg/l (+3).

- sudden loss of visual acuity (+3)

- Morning stiffness (shoulders or neck), claudication (jaw or tongue), new-onset temporal headache, tender scalp, TA abnormalities on vascular examination, bilateral axillary artery involvement on imaging, and FDG-PET activity in aorta (+2 each).

Based on these 10 criteria, a cumulative score ≥6 was determined for classification as an RZA (Table 1). When these criteria were tested in the validation data set, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.91 (95% CI; 0.88-0.94), with a sensitivity of 87.0% (95% CI; 82.0-91.0%) and specificity of 94.8% (95% CI; 91.0-97.4%) [5,6].

It is not uncommon for giant cell arteritis to be associated with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR). There is debate as to whether PMR is a minor variant of RZA. The speaker referred to a secondary analysis published in 2022 that more than a quarter of patients with PMR had subclinical RZA. If this is suspected, performing imaging studies is informative [7].

Systemic glucocorticoids as standard of care

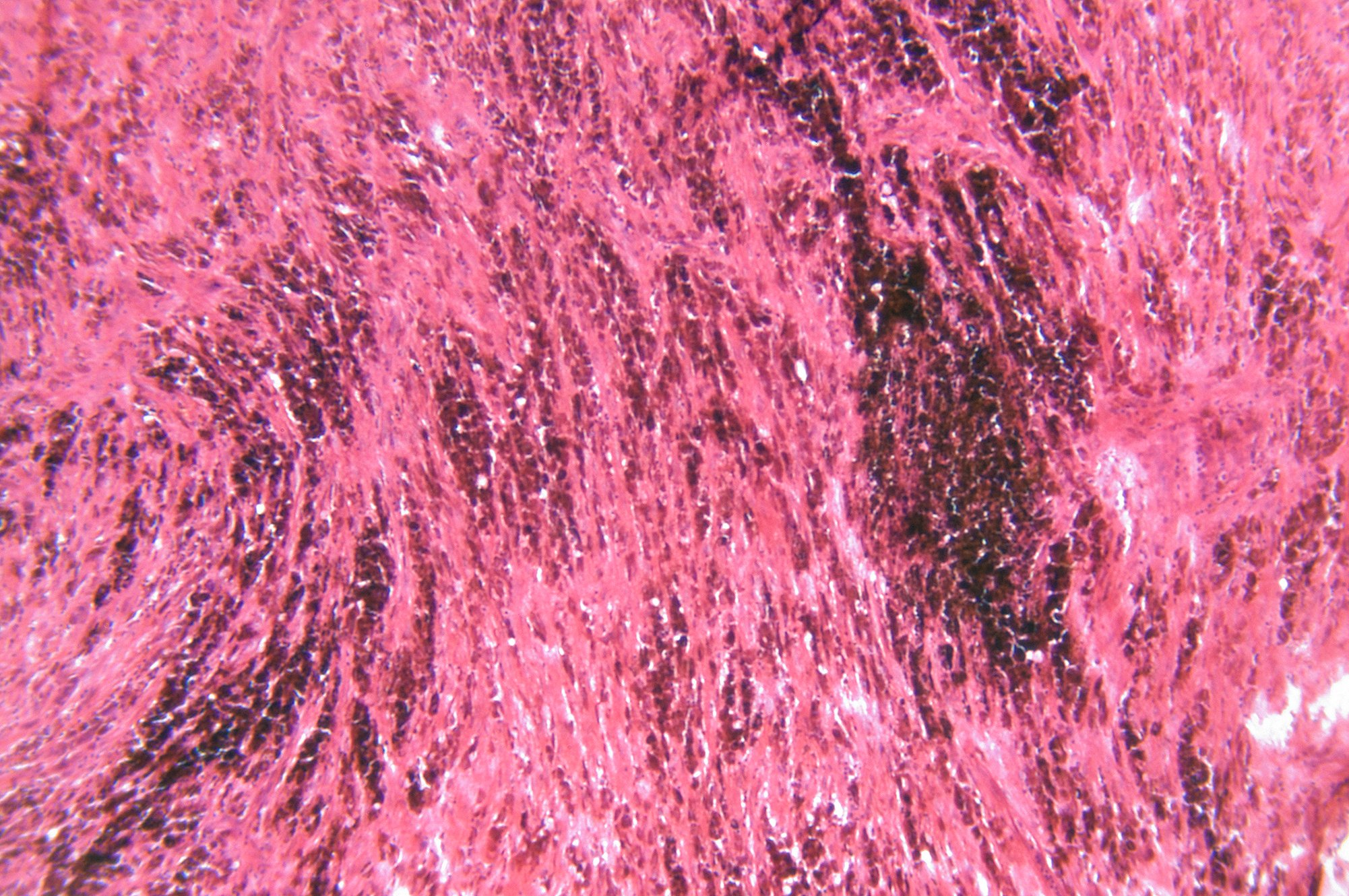

The most serious complication of giant cell arteritis remains permanent loss of vision. This is most often due to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy involving the posterior ciliary arteries or occlusion of the central retinal artery [8]. Before the introduction of glucocorticoid therapy for RZA, permanent vision loss occurred in 40-48% of cases. In recent decades, this rate decreased to 10-20%, Prof. Daikeler reported [2,3]. In Switzerland, the recommendation to immediately initiate systemic glucocorticoid therapy when RZA is suspected has become accepted in everyday practice [3]. If left untreated, the risk for bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is high [3,9]. Transient visual symptoms, older age, and lower levels of inflammatory markers in the blood are risk factors for impending vision loss [3]. Once vision loss has occurred, it is usually permanent, and glucocorticoids are administered to preserve remaining vision [10].

“Consider tapering” and tocilizumab as an add-on.

In active RZA, it is recommended to immediately initiate high-dose glucocorticoid therapy (40-60 mg/day prednisone equivalent) to induce remission [11]. Once the disease is under control, the glucocorticoid (GC) dose can be reduced to a target dose of 15-20 mg/day within 2-3 months and to ≤5 mg/day after one year. Although the risk of relapse is high in giant cell arteritis, a substantial number of patients with RZA on GC monotherapy remain without relapse, so that the GC dose can be reduced to a target of ≤5 mg/day after one year – a dose that is considered acceptable in terms of safety by the EULAR task force [11].

The additional administration of tocilizumab (TCZ) may reduce the risk of relapse and the cumulative GC burden compared with GC monotherapy. This is demonstrated by two randomized-controlled clinical trials in patients with RZA [12,13]. Given the high prevalence of comorbidities in the subpopulation of elderly RZA sufferers, the decision to use concomitant TCZ therapy in individual patients should be weighed against the potential risks for treatment-related complications. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have been found to be at increased risk of lower intestinal perforations with TCZ [11,14]. In contrast to tocilizumab, methotrexate is not significantly associated with lower relapse rates, according to the findings of a meta-analysis published in 2021 [15].

Finally, the speaker referred to the “National cohort for Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases” (SCQM) [2,16]. It is hoped that these registry data will provide new insights relevant to therapy.

Congress: Allergy and Immunology Update (SGAI)

Literature:

- Ponte C, Águeda AF, Luqmani RA: Clinical features and structured clinical evaluation of vasculitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2018; 32: 31-51.

- «GCA management», Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Daikeler, Allergy and Immunology Update, 27.–29.1.2023

- Hemmig AK, et al: Long delay from symptom onset to first consultation contributes to permanent vision loss in patients with giant cell arteritis: a cohort study. RMD Open 2023 Jan; 9(1):e002866.

- Prior JA, et al: Diagnostic delay for giant cell arteritis – a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2017; 15: 120

- Ponte C, et al; DCVAS Study Group. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/EULAR Classification Criteria for Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022; 74(12): 1881-1889.

- «Grossgefässvaskulitiden: Gemeinsame ACR/EULAR-Klassifikationskriterien 2022», 01.2023,

www.rheumamanagement-online.de/literatur-news/detailansicht/gemeinsame-acr-eular-klassifikations

criteria-2022-published, (last accessed Feb. 28, 2023). - Hemmig AK, et al: Subclinical giant cell arteritis in new onset polymyalgia rheumatica A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2022 Aug; 55: 152017.

- Biousse V, Newman NJ: Ischemic optic neuropathies. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2428-2436.

- Liu GT, et al: Visual morbidity in giant cell arteritis. Clinical characteristics and prognosis for vision. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 1779-1785.

- Héron E, et al: Ocular complications of giant cell arteritis: an acute therapeutic emergency. J Clin Med 2022; 11. doi:10.3390/jcm11071997. [Epub ahead of print: 02 04 2022].

- Hellmich B, et al: 2018 Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020; 79(1): 19-30.

- Stone JH, et al: Trial of tocilizumab in giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 317-328

- Villiger PM, et al: Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 2016; 387: 1921-1927.

- Strangfeld A, et al: Risk for lower intestinal perforations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab in comparison to treatment with other biologic or conventional synthetic DMARDs. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 504-510

- Gérard AL, et al: Efficacy and safety of steroid-sparing treatments in giant cell arteritis according to the glucocorticoids tapering regimen: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med 2021; 88: 96-103.

- “National cohort for Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases” (SCQM), www.scqm.ch,(last accessed Feb. 28, 2023).

- Stanca HT, et al: Giant cell arteritis with arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Rome J Morphol Embryol 2017; 58: 281–285.

- Jianu DC, et al: Ultrasound Technologies and the Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9121801

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(3): 30–32