Autoimmune thyroiditis of the Hashimoto type progresses insidiously in most patients and in the long term leads to destruction of the thyroid gland resulting in hypothyroidism. However, there are also phases with passive hyperthyroidism (hashitoxicosis). The disease can occur at any age, but is more common in middle and older adulthood. Women are affected much more frequently than men. Treatment with thyroid hormones allows those affected to lead a normal life.

The most common cause of primary hypothyroidism is Hashimoto’s thyroiditis – an autoimmune thyroiditis first described in 1912 by the Japanese pathologist Hikaru Hashimoto [1]. In the course of this chronic inflammatory thyroid disease, immunologically induced progressive destruction of the thyroid parenchyma occurs. There is an association with other autoimmune diseases such as Addison’s disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, or type 1 diabetes (Box) [2]. In addition to genetic predisposition, age, gender, and environmental factors such as viral exposure and stress may play a role in the development of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [3]. Excessive iodine intake and radiation exposure are also possible triggers of this autoimmune thyroiditis. The second most common cause of hypothyroidism is idiopathic; somewhat less common are posttherapeutic hypothyroidism, occurring, for example, after radiation or total/subtotal thyroidectomy. Congenital hypothyroidism (cretinism) is now rare in Switzerland [1]. Drug-induced hypothyroidism is present in only about 2.5% of cases. In addition to thyrostatic agents, this side effect may occur with long-term treatment with amiodarone, lithium, interferon-α, or tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Not a thyroid disease, but associated with changes in thyroid hormones, is “euthyroid sick syndrome” [1]. In this context, patients with an increased catabolic metabolic state, such as occurs during surgery, large-scale trauma, inflammation, or malnutrition, experience a transient drop in thyroid hormones (TSH low, T3 and T4 low) [4,8].

Gradual progression and non-specific symptoms

At the onset of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and in phases of particularly high inflammatory activity, there may be passive hyperthyroidism. Symptoms such as sweating are often mistakenly classified as menopausal symptoms in menopausal women. As the disease progresses, the symptoms of hypothyroidism come to the fore. Bradycardia, hypertension, hyporeflexia, and hypothermia are typical. Changes in the voice (deep, hoarse) and skin (pale yellowish) are also common, according to Prof. Roger Lehmann, MD, University Hospital Zurich [1]. Hypothyroid coma rarely occurs,

Laboratory diagnostics including detection of antibodies

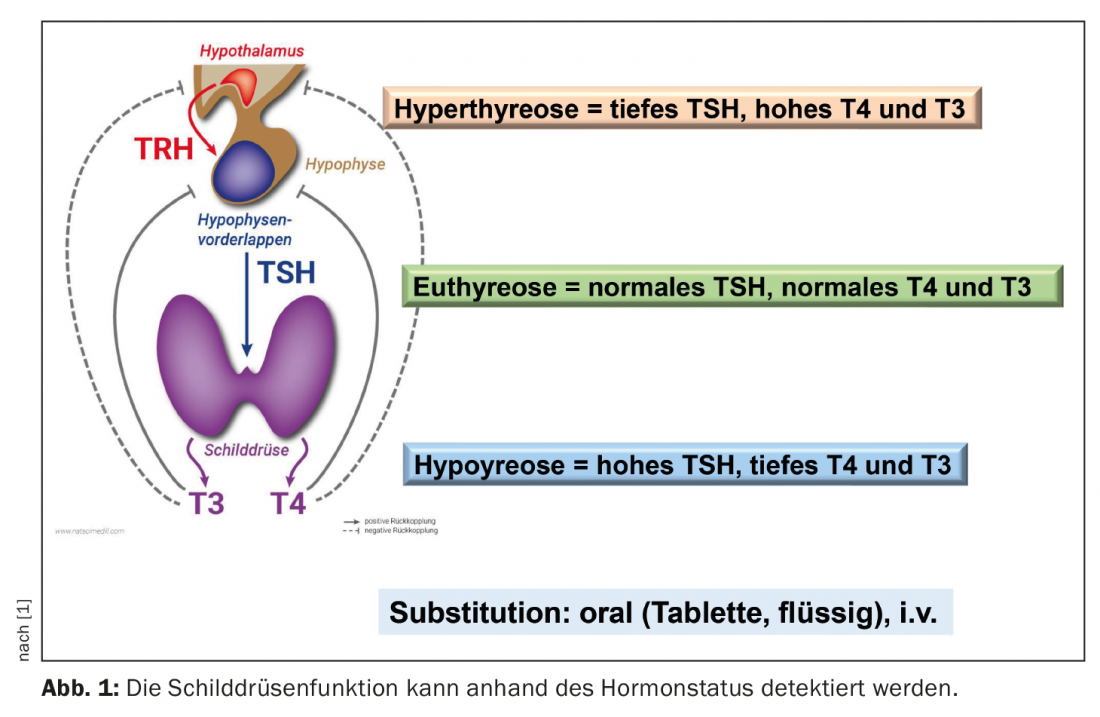

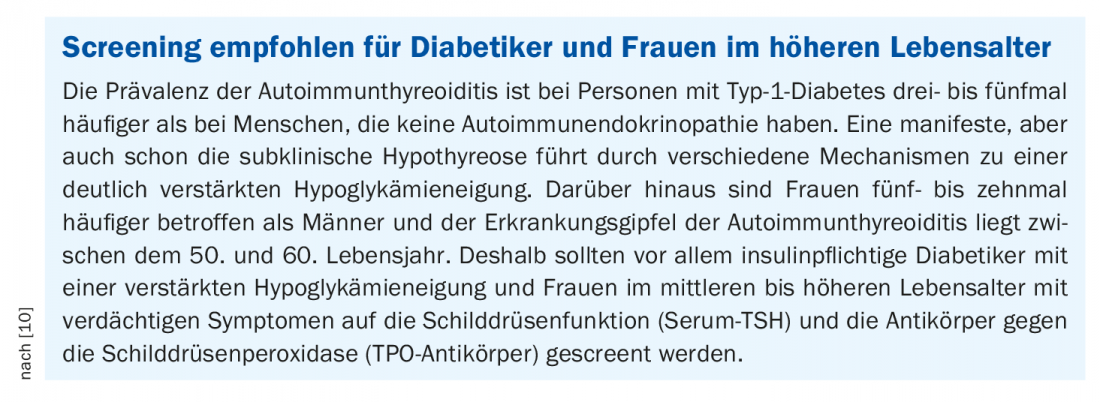

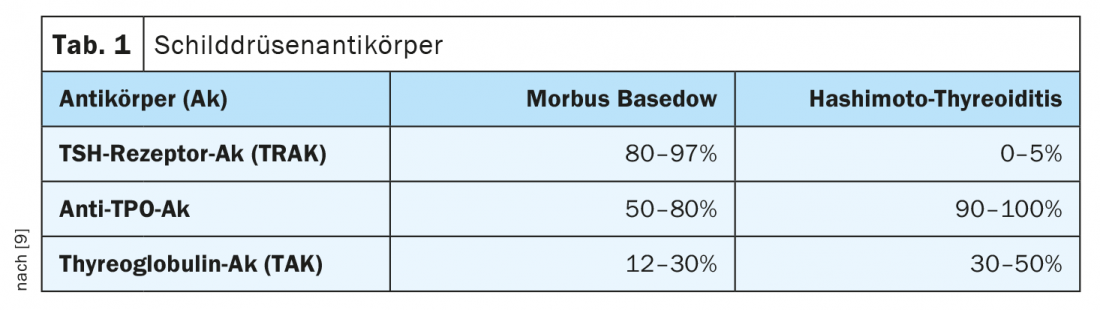

In addition to the determination of the functional parameters TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone from the pituitary gland), fT4 (free thyroxine) and fT3 (free triiodothyronine), antibody detection can be informative. While in latent hypothyroidism only serum TSH is elevated with normal fT3 and fT4 levels, clinically manifest hypothyroidism (TSH elevated, fT4 and/or fT3 decreased) develops later in the course. Antibodies to thyroglobulin (TAK) and those to the thyroid enzyme peroxidase (TPO-AK) indicate whether the thyroid disease is autoimmune. High TPO titers are detectable in over 80% of Hashimoto’s patients (Table 1) [1,9]. However, elevated levels of these antibodies are also found in more than half of patients with Graves’ disease.

Perform sonography and, in case of doubt, scintigraphy

Sonographically, Hashimoto’s syndrome shows an echo-poor thyroid gland with inhomogeneous structure and isolated echo-rich and scarred areas. Overall, the thyroid gland is usually reduced in size, but hypertrophic forms with accompanying goiter also exist. Scintigraphically, normal uptake of the tracer (technetium or iodine-123) can be distinguished from thyroiditis (no uptake of the tracer), Graves’ disease (homogeneous increased uptake), or toxic adenoma (increased uptake) [1].

Substitution with L-thyroxine as therapy of choice

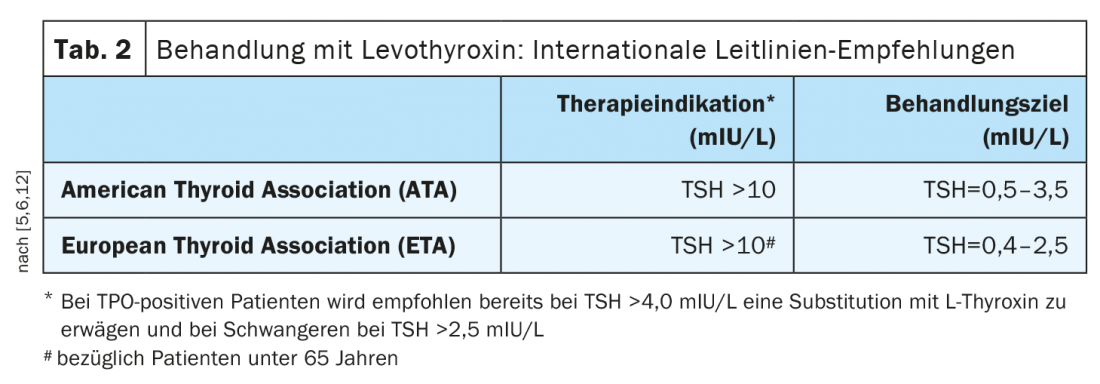

The standard therapy of hypothyroidism is taking levothyroxine (Table 2) [1]. This active ingredient corresponds to natural thyroxine (T4). The tablets or capsules are taken with water in the morning on an empty stomach, at least half an hour before breakfast. According to most international guidelines, treatment is indicated at TSH levels >10 mIU/L [5,6]. The European Thyroid Association points out that depending on symptoms, treatment may also be considered if levels are repeatedly between 5-10 mIU/L. [7]. In TPO-positive patients, international guidelines also advise considering substitution with L-thyroxine at TSH >4.0 mIU/L and in pregnant women at TSH >2.5 mIU/L [12]. As a dosage regimen, Prof. Lehmann recommends taking 1.6 µg/kg body weight. In elderly patients (>60 years) and individuals with coronary artery disease, a reduced dose is appropriate. In general, dose adjustments can be made as part of monitoring the course of therapy when target values are reached. Target fT4 levels after two weeks are 14-16 nmol/l, and TSH should be in the range of 0.5-2 mU/l over the long-term (after 6 weeks at the earliest) [1]. With adequate T4 substitution, the life expectancy of affected individuals is normal and patients are usually symptom-free. In subclinical hypothyroidism, i.e., patients with elevated TSH and fT4 within the normal range, control testing is recommended before deciding on therapy [6].

Congress: Forum for Continuing Medical Education

Literature:

- Lehmann R: The most common thyroid diseases in practice. Prof. Dr. med. Roger Lehmann, Forum for General and Internal Medicine, 17-20.11.2021

- Sheu S-Y, Schmid KW, Inflammatory thyroid diseases, Pathologist 2003; 24: 339-347.

- Dong YH, Fu DG: Autoimmune thyroid disease: mechnism, genetics and current knowledge. Euro Rev Med Pharmocol Schi 2014; 18: 3611-3618

- Lee S, Farwell AP. Euthyroid Sick Syndrome. Compr Physiol 2016;6: 1071-1078

- Jonklaas J, et al: Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: Prepared by the american thyroid association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid 2014; 24: 1670-1751.

- Pearce SH, et al: 2013 ETA guideline: Management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2013;2: 215-228.

- Calissendorff J, Falhammar H: To Treat or Not to Treat Subclinical Hypothyroidism, What Is the Evidence? Medicina (Kaunas) 2020; 56(1): 40. doi: 10.3390/medicina56010040

- Schipani F, et al: A postoperative condition associated with malnutrition. Swiss Med Forum 2019; 19(3738): 620-622.

- Krull I, Brändle M: Hyperthyroidism: Diagnosis and Therapy. Switzerland Med Forum 2013; 13(47): 954-960.

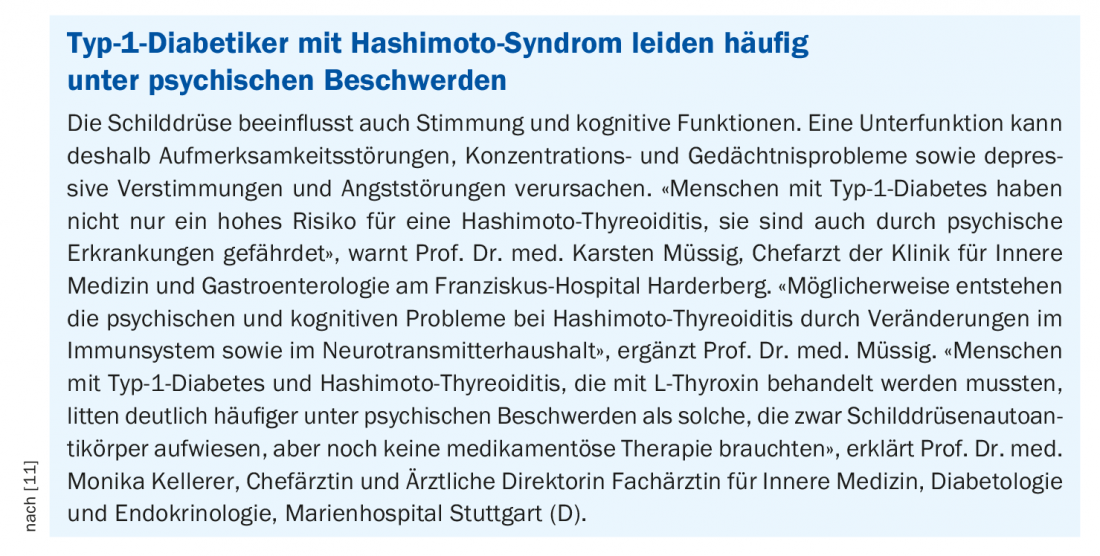

- Schumm-Draeger PM: Thyroid and diabetes: interaction is underestimated. Dtsch Arztebl 2016; 4: 113(43): DOI: 10.3238/PersDia.2016.10.28.01

- DDG 2021: “Type 1 diabetes and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis frequently occur together”, German Diabetes Society (DDG), 29.04.2021.

- De Groot l, et al: Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(8): 2543-2565.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(2): 26-27

CARDIOVASC 2022; 21(2): 36-37