Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of the lower digestive system, and the disorder is more common in women than in men. IBS is one of the most common gastrointestinal dysfunctions, it leads to a significant impairment of the quality of life of those affected and also causes large direct as well as indirect costs (especially due to work absenteeism and reduced productivity during work). The review article presents current recommendations for action regarding the diagnosis and therapy of IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of the lower digestive system [1] with a worldwide estimated prevalence of approximately 11% [2] and an estimated incidence of approximately 1.5% [3], and the disorder is more common in women than in men [4]. With a prevalence of 5-10% in Germany [2], IBS is one of the most common gastrointestinal dysfunctions [5]. In this context, IBS leads to a considerable impairment of the quality of life of those affected [6] and also causes large direct costs (e.g., due to visits to the doctor, medication, diagnostics, hospitalization, etc.) as well as indirect costs (especially due to absences from work and reduced productivity during work) [7]. The present review article takes the revised S3 guideline for IBS published in Germany in 2021 [7] as an opportunity to present current recommendations for action regarding the diagnosis and therapy of IBS. This guideline was developed in collaboration with the relevant professional societies in Germany, but also with the participation of the Swiss Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, and is also valid in Switzerland.

According to the updated guideline [7], IBS is present when the following three criteria are met:

- chronic, i.e. lasting longer than three months, or recurrent, bowel-related complaints (e.g. abdominal pain, flatulence), usually accompanied by changes in bowel movements;

- the complaints lead the person concerned to seek help and/or worry in this respect and the complaints are so severe in this respect that the quality of life is relevantly impaired;

- no changes characteristic of other clinical pictures are present, which are responsible for the symptoms present.

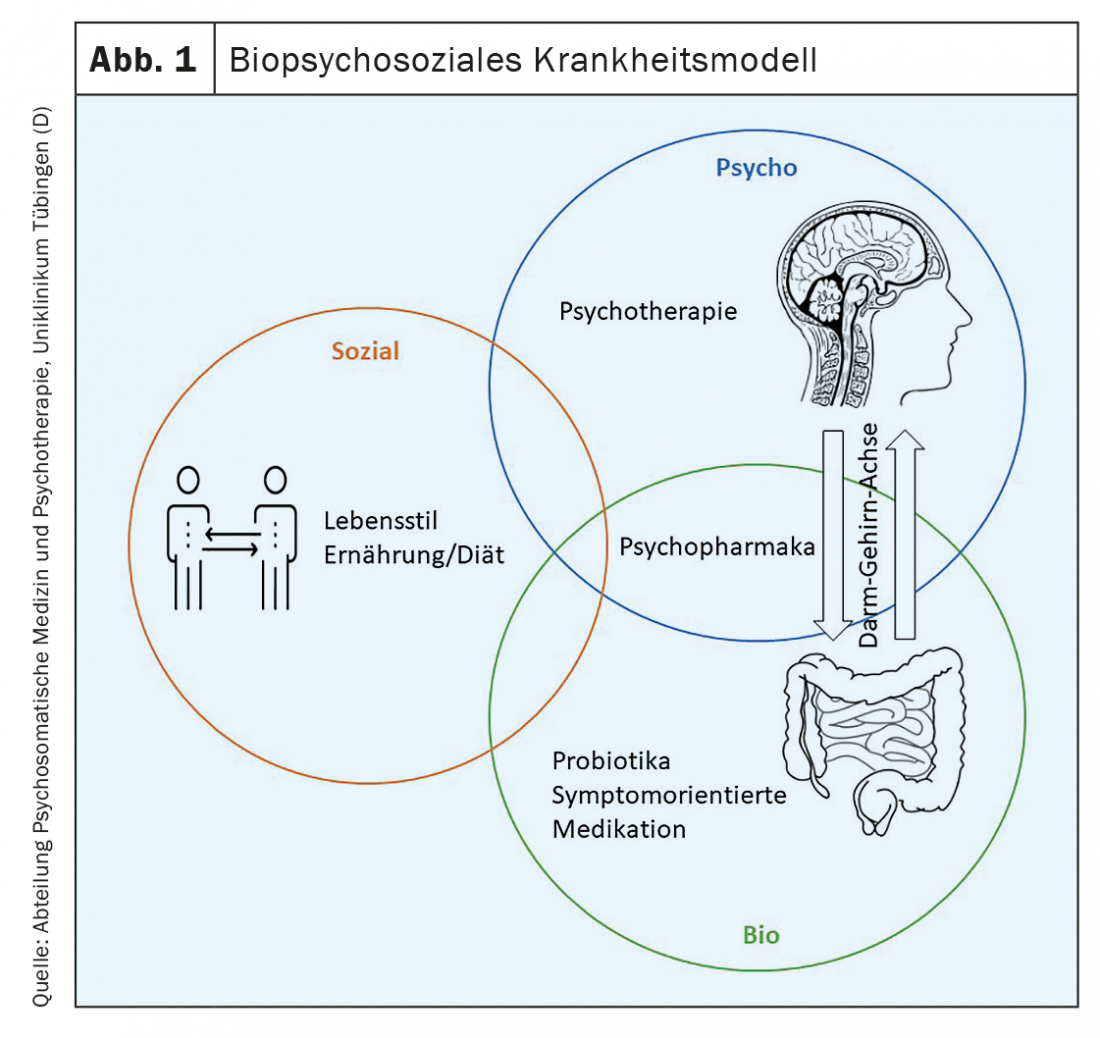

Prognostically, IBS symptoms spontaneously regress in a proportion of patients, but are often chronic, and IBS does not appear to be associated with the development of other gastrointestinal or other serious diseases and does not have increased mortality [8]. However, a high comorbidity with mental disorders has been shown [9]. Due to the lack of curative options, the treatment of IBS is mainly aimed at alleviating the symptoms [10]. Therapeutic measures in this regard against the background of the biopsychosocial model are the subject of this article.

Note: Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional disorder of the lower digestive system that is associated, among other things, with persistent, i.e. lasting longer than three months or recurrent, bowel-related complaints such as abdominal pain, flatulence and changes in bowel movements, and which significantly impairs the quality of life of those affected. to a significant extent.

Pathogenesis

Based on a biopsychosocial model, various somatic (e.g., [Epi]-genetics, infections), psychological (e.g., chronic stress, illness behavior), and social aspects (e.g., socioeconomic status) are thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of IBS [11]. Thus, numerous biological alterations have since been identified that are associated with IBS symptomatology [1,10]. For example, the most common abnormalities studied include motility disturbances, altered enteric immune response, and altered mucosal function manifested by impaired intestinal barrier and secretion, as well as visceral hypersensitivity. In relation to visceral hypersensitivity, altered signal processing in brain regions responsible for emotional or sensorimotor processing of visceral signals has been identified at the neurological level [12]. This finding may provide a plausible explanation for the association between IBS and psychological factors and further highlights the importance of the gut-brain axis in the pathophysiology of IBS [13].

In the sense of such a gut-brain-axis involvement, a reduced parasympathetic activation seems to be detectable especially in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), whereby this reduced activation could in turn be related to the severity of complaints, abuse experiences and depression symptoms [14]. A large number of studies further demonstrate sympathetic overactivation in patients with IBS [15], which in turn appears to be associated with increased stress levels [16]. Furthermore, against the background of an altered gut-brain axis, patients with IBS show stress-induced changes in gastrointestinal motility, autonomic tone, and HPA axis response, among others [17].

Recently, the influence of the microbiome on the gut-brain axis has also been studied in more detail in relation to the development and maintenance of IBS [18]. Here, changes in both the quantity and quality of the total intestinal bacteria have been found in patients with IBS [18], and stress and the intestinal bacterial flora may in turn interact with each other and influence, for example, the visceral pain perception of patients with IBS [19]. In addition, the changes in the microbiome in pa-tients with IBS may provide an explanatory approach to the effects of infections and antibiotic therapies in the development of IBS.

With regard to genetic predispositions, IBS shows a familial clustering, partly over several generations: The probability of developing IBS is increased by a factor of two to three in a relative of someone suffering from IBS [20]. Furthermore, initial study results suggest that epigenetic factors may also be involved in the genesis of RDS [21].

High comorbidity with affective disorders, especially anxiety and depressive disorders, is well documented in IBS [22]. Chronic stress and psychological comorbidities are considered risk factors for the development and maintenance of IBS [23]. Thus, increased anxiety and depressive symptoms [24] and reduced quality of life [25] have been shown to be predictors of initial manifestation of IBS. Furthermore, the prevalence of stressful life events in the past history (e.g., abuse experiences or childhood trauma) is increased compared to healthy comparison persons [26]. In addition, it has been shown that psychometrically recorded anxiety and depressive symptoms are positively correlated with pain severity [27] and can negatively affect the feeling of fullness and bloating [28]. However, anxiety and depressive disorders may also develop secondarily as a result of the stress of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms [24]. In addition, aspects of coping with the disease or coping strategies in dealing with stress and symptoms (especially catastrophizing) as well as disease behavior learned through the social environment (e.g., interpretation of body perceptions as “problematic symptoms,” maladaptive avoidance behavior, etc.) seem to play an important role in the development and maintenance of IBS [29–31]. The influence of personality traits is also considered in some studies: in particular, the personality scale neuroticism seems to play a role and should be further investigated in terms of vulnerability to develop RDS [31].

In summary, against the background of a biopsychosocial model, complex interaction processes between stress, psychological comorbidity and gastrointestinal symptoms in the sense of a vicious circle seem to be obvious in the pathogenesis of IBS [32].

Note: The biopsychosocial model considers various somatic and psychosocial factors within the pathophysiology of IBS and integrates their multifaceted interaction processes. Thus, numerous biological alterations have since been identified that are associated with IBS symptomatology. A plausible explanation for the association between IBS and psychological factors is offered primarily by the gut-brain axis. Complex interaction processes between stress, psychological comorbidity and gastrointestinal symptoms in the sense of a vicious circle seem to be obvious.

Therapy

Corresponding to a very heterogeneous clinical picture with regard to pathogenesis, manifestation of symptoms and the resulting impairments in everyday life, there is also a very broad spectrum of potentially effective treatment principles against the background of the biopsychosocial disease model (Fig. 1). As a result of this heterogeneity, it is not possible to name “the” standard therapy for IBS; rather, each therapeutic intervention initially has a probationary character. According to the S3 guideline, combinations of different drug substances as well as combinations of drug and non-drug treatments should be considered if there is only a partial response to monotherapy and/or for the treatment of various symptomatic complaints [7]. These treatment components are discussed in more detail below.

Lifestyle: The current data on evidence-based recommendations for beneficial lifestyle changes (e.g., not smoking, low alcohol consumption, conscious eating, sufficient exercise, enough sleep, stress reduction, etc.) is currently sparse and (despite some positive observations) still contradictory [33]. Nevertheless, there are few high-quality studies showing that physical exercise in particular can have a positive effect (possibly long-term) on IBS symptoms over a period of twelve weeks [34,35].

Note: According to the updated S3 guideline, integrative and multimodal treatment concepts should be used for the treatment of IBS in cases of only partial response to monotherapy and/or for the treatment of different types of symptoms.

Nutrition/diet: According to the S3 guideline, nutritional medicine/nutritional therapy measures are a meaningful component of a therapy concept for patients with IBS [7]. Thus, in patients with IBS with predominantly obstipative symptoms (IBS-O), symptom improvements could be achieved as a result of an increased intake of dietary fiber (preferably of a soluble nature) [36]. If pain, bloating and diarrhea are the dominant symptoms, a so-called low-FODMAP diet should be recommended. In this case, fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) should first be avoided in the food intake under accompanying medical nutritional counseling (elimination phase). FODMAPs are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine. At the latest in the colon, they then become osmotically active and rapidly fermented, so that abdominal pain, flatulence and soft, bulky stools may follow. Once symptoms improve as a result of the elimination phase, foods with higher FODMAP content can be gradually reintroduced [37]. According to this scheme, it is possible to find out which foods trigger or worsen symptoms and which are tolerated (phase of tolerance finding). All foods that could be eaten symptom-free are subsequently included in the long-term nutrition plan (phase of long-term nutrition). In this regard, a number of studies have demonstrated improvement in IBS symptoms with restriction of FODMAPs [38].

Note: Physical exercise can have a have a positive effect on IBS symptoms.

Symptom-oriented medication: Pharmacotherapy of IBS should always be symptom-oriented and take into account the dominant symptoms [7]. According to the guideline, medication with the peristaltic inhibitor loperamide (µ-opioid receptor agonist) is recommended for the treatment of IBS-D. Despite good evidence of efficacy, the updated guideline states that eluxadoline, also an opioid-based agent, should be considered only in selected individual cases of otherwise refractory IBS-D because its use appears to be associated with acute pancreatitis and, in particular, should not be used in patients after cholecystectomy, with biliary tract disease, alcoholism, liver cirrhosis, and sphincter-Oddi dysfunction. The cholesterol absorption inhibitor colestyramine should be used to treat chologenic diarrhea. Colesevelam can also be used against the same pathophysiological background. Furthermore, off-label therapy with 5-HT3 antagonists (e.g., Ondan-setron) should be attempted in otherwise refractory IBS-D [7].

Note: Especially the so-called “low-FODMAP diet” in particular can demonstrably alleviate IBS symptoms.

Macrogol-type laxatives should be recommended for the treatment of constipation symptoms. If there is no response to conventional laxatives or they are not tolerated, the 5-HT4 agonist prucalopride should be tried for treatment. Furthermore, the peptide drug linaclotide (guanylate cyclase C agonist) should be recommended for laxative-refractory constipation and especially for concomitant abdominal pain and flatulence, but treatment is not reimbursed in Germany. In the absence of regulatory approval and limited availability in Germany, lubiprostone from the group of chloride channel activators should be considered only in selected individual cases of otherwise therapy-refractory RDS-O [7].

According to the S3 guideline, spasmolytics such as butylscopolamine should be recommended for the treatment of IBS-associated pain [7]. In addition, peppermint oil from the group of phytotherapeutics has been shown to be effective in treating IBS symptoms of pain and bloating and should be considered accordingly. Other phytotherapeutic preparations such as the plant mixture STW-5 (Iberis Amara, angelica root, chamomile flowers, caraway fruits, milk thistle fruits, lemon balm leaves, peppermint leaves, celandine and liquorice root) and STW-5-II (Iberis Amara, chamomile flowers, caraway fruit, lemon balm leaves, peppermint leaves, and licorice root) were able to achieve symptom relief, especially of abdominal pain, and should be individually integrated into the treatment concept.

Furthermore, the antibiotic rifaximin, which is not approved for this indication in Germany, should be considered for the treatment of flatulence symptoms in otherwise refractory IBS without constipation. However, the question of a possible development of resistance in the case of recurrent and/or long-term use remains unresolved at the current time [7].

Note: Drug therapy for IBS should always be symptom-oriented and take into account the dominant symptoms. For example, peristaltic inhibitors are primarily used in the treatment of IBS-D, and macrogol-type laxatives are primarily used in the treatment of constipation symptoms. In the treatment of IBS-associated pain, spasmolytics such as butylscopolamine are the main drugs used.

Probiotics: Regarding the general efficacy of probiotics for the treatment of IBS-associated symptoms, no firm statement can be made at this time due to a large methodological and qualitative heterogeneity of the study situation. However, for individual probiotic strains commonly used in Germany (e.g. Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus) as well as multispecies products, significant improvements could be achieved in randomized controlled clinical trials both for IBS-typical symptoms such as pain, flatulence and changes in stool frequency and consistency as well as for the quality of life and the general satisfaction of the study participants. According to the guideline, every treatment attempt with probiotics should be carried out on a trial basis and only continued after convincing relief of symptoms [7].

Note: Individual probiotic strains as well as multispecies products have already been proven to be effective, but a general effectiveness of probiotics has not yet been proven, so that every treatment attempt with probiotics is initially of a probationary nature.

Psychotropic drugs: According to the guideline, the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline should be used in adults for the treatment of pain, among other conditions (with the exception of constipation), but should not be used in elderly patients if possible due to its anticholinergic side effect [7]. Furthermore, because tricyclic antidepressants prolong orocecal as well as total gastrointestinal transit time, it seems appropriate to use tricyclics in RDS-D [39]. In contrast, SSRI-type antidepressants shorten orocecal transit time, so it seems reasonable to use them in RDS-O. However, since the study situation on the use of SSRIs in IBS has so far yielded inconsistent results and, moreover, there is no approval for the use of SSRIs for IBS in Germany, according to the updated guideline, SSRI-type antidepressants can only be considered in cases of psychological comorbidity. In addition, the use of the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) duloxetine may be considered in adults with comorbid anxiety and depressive disorder [40].

Note: The tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline in particular is used in adults for the treatment of IBS-associated pain, among other things. According to the updated guideline, SSRI-type antidepressants can only be used in cases of psychiatric comorbidity. be considered.

Psychotherapy: According to the S3 guideline, psychoeducational elements, such as providing information about IBS and the relationship between stressful emotions and the occurrence of symptoms, are useful as a cost-effective offer in the context of other treatment [7], as they have been shown to have positive effects on the symptoms as well as the quality of life of patients with IBS [9]. In addition, strategies for dealing with stress and/or coping with illness (coping) should be recommended individually as adjuvant measures in the sense of guided self-help measures [41]. In several studies, a reduction in IBS symptoms and an increase in the quality of life of those affected were achieved, whereby initial results indicate that online-based offers(eHealth interventions) in particular can be a helpful addition [42].

In addition, specialist psychotherapeutic procedures are to be offered as part of the treatment concept if there is a suitable indication. Regarding the basic indication for psychotherapy, independent of the respective procedure, the patient’s wish, a significantly impaired quality of life due to gastrointestinal symptoms, and any psychological comorbidities are decisive [41]. In this context, there is strong evidence for the effectiveness of psychotherapies in IBS, with by far the most studies published on cognitive behavioral therapy. This proved to be effective and superior to control conditions [43]. Fewer studies exist on psychodynamic procedures, but they too have been shown to be effective [43]. Mindfulness-based therapies have also been shown to have small to moderate positive effects in individual studies, but due to the currently still limited number of studies, no conclusive recommendation for these therapies has been made in the guidelines [7].

Gut-directed hypnosis ( GDH) is considered the only organ-specific psychotherapeutic procedure in the treatment of IBS, for which several meta-analyses have reported positive effects on symptom improvement with medium effect sizes [44,45]. However, severe mental illnesses (e.g., severe depression and panic disorders) are considered relative contraindications in this regard.

According to the guideline, relaxation therapy (e.g., Jacobson’s progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training) should not be offered as monotherapy but as part of a multimodal treatment concept [7]; the same applies to mindfulness-based yoga. If psychotherapy is indicated, it may be combined with psychopharmacotherapy, if appropriate [41].

Note: Psychoeducational elements have been shown to be useful as a cost-effective service in the context of other treatment. Due to the repeatedly proven effectiveness of psychotherapy in RDS, specialized psychotherapeutic procedures should be offered as part of the treatment concept if indicated (e.g., in the case of psychological comorbidity). Abdominal-directed hypnosis is used as an organ-specific psychotherapeutic procedure in the treatment of IBS.

Conclusion

The biopsychosocial model considers various somatic and psychosocial factors within the pathophysiology of IBS and integrates their multifaceted interaction processes. In addition, therapeutic starting points can be identified and implemented on a biological, psychological and social level. Against this background, integrative and multimodal treatment concepts seem particularly promising in the therapy of IBS and should be further investigated for their efficacy in clinical research.

Take-Home Messages

- Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional disorder of the lower digestive system that is associated with, among other things, persistent bowel-related symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel movements, leading to significant distress for those affected.

- Based on a biopsychosocial model, it can be assumed that various somatic, psychological and social aspects are involved in the pathophysiology of IBS. Complex interaction processes between stress, psychological comorbidity and gastrointestinal symptoms in the sense of a vicious circle are obvious.

- Accordingly, there is a wide range of therapeutic interventions to manage the symptoms of IBS and to improve the quality of life of those affected. Therapeutic starting points can be identified and implemented on a biological, psychological and social level.

- Against this background, integrative and multimodal treatment concepts seem particularly promising in the therapy of IBS and should be further investigated for their efficacy in clinical research.

Literature:

- Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al: Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016 Feb 18; S0016-5085(16)00222-5.

- Lovell RM, Ford AC: Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2012; 10(7): 712-721.e4.

- Halder SLS, Locke GR, Schleck CD et al: Natural history of functional fastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007; 133(3): 799-807.e1.

- Andrews EB, Eaton SC, Hollis KA, et al: Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large web-based survey. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2005; 22(10): 935-942.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK: Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2017; 6(11): 99.

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al: The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 2000; 119(3): 654-660.

- Layer P, Andresen V, Allescher H, et al: Update S3-Leitlinie Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Definition, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Therapy of Irritable Bowel Syndrome of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) and the German Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility (DGNM). AWMF 2021.

- Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al: Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut 2007; 56(12): 1770-1798.

- Weibert E, Stengel A: The role of psychotherapy in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2019; 69(9-10): 360-371.

- Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al: Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 16014.

- Drossman DA: Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6): 1262-1279.e2.

- Mayer EA, Gupta A, Kilpatrick LA, Hong JY: Imaging brain mechanisms in chronic visceral pain. Pain 2015; 156: S50-63.

- Raskov H, Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC, Rosenberg J: Irritable bowel syndrome, the microbiota and the gut-brain axis. Gut Microbes 2016; 7(5): 365-383.

- Mazurak N, Seredyuk N, Sauer H et al: Heart rate variability in the irritable bowel syndrome: a review of the literature. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2012; 24(3): 206-216.

- Liu Q, Wang EM, Yan XJ, Chen SL: Autonomic functioning in irritable bowel syndrome measured by heart rate variability: A meta-analysis. Journal of Digestive Diseases 2013; 14(12): 638-646.

- Heitkemper M, Jarrett M, Cain K, et al: Increased urinary catecholamines and cortisol in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(5): 906-913.

- Chang L: The role of stress on physiological responses and clinical symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2011; 140(3): 761-765.

- Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G: Irritable bowel syndrome: a microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(39): 14105-14125.

- Moloney RD, Johnson AC, O’Mahony SM, et al: Stress and the microbiota-gut-brain axis in visceral pain: relevance to irritable bowel syndrome. CNS Neurosci Ther 2016; 22(2): 102-117.

- Saito YA: The role of genetics in IBS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2011; 40(1): 45-67.

- Dinan TG, Cryan J, Shanahan F et al: IBS: An epigenetic perspective. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 7(8): 465-471.

- Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR: Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology 2002; 122(4): 1140-1156.

- Tanaka Y, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S, Drossman DA: Biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17(2): 131-139.

- Koloski NA, Jones M, Kalantar J, et al: The brain–gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: a 12–year prospective population–based study. Gut 2012; 61(9): 1284-1290.

- Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, et al: Irritable bowel syndrome: a 10-yr natural history of symptoms and factors that influence consultation behavior. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103(5): 1229-1239; quiz 1240.

- Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MAL, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE: Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103(3): 765-774; quiz 775.

- Elsenbruch S, Rosenberger C, Enck P et al: Affective disturbances modulate the neural processing of visceral pain stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome: an fMRI study. Gut 2010; 59(4): 489-495.

- Van Oudenhove L, Törnblom H, Störsrud S, et al: Depression and somatization are associated with increased postprandial symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(4): 866-874.

- Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z et al: Effects of coping on health outcome among women with gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med 2000; 62(3): 309-317.

- Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, et al: Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; S0016-5085(16)00218-3.

- Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Thakur ER, et al: The impact of physical complaints, social environment, and psychological functioning on IBS patients’ health perceptions: looking beyond GI symptom severity. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109(2): 224-233.

- Blanchard EB, Lackner JM, Jaccard J et al: The role of stress in symptom exacerbation among IBS patients. J Psychosom Res 2008; 64(2): 119-128.

- Kang SH, Choi SW, Lee SJ, et al: The effects of lifestyle modification on symptoms and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective observational study. Gut Liver 2011; 5(4): 472-477.

- Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, et al: Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(5): 915-922.

- Johannesson E, Ringström G, Abrahamsson H, Sadik R: Intervention to increase physical activity in irritable bowel syndrome shows long-term positive effects. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(2): 600-608.

- Zuckerman MJ: The role of fiber in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: therapeutic recommendations. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 40(2): 104-108.

- Hetterich L, Stengel A: Nutritional aspects in irritable bowel syndrome – an update. Current Nutritional Medicine 2020; 45(4): 276-285.

- Rao SSC, Yu S, Fedewa A: Systematic review: dietary fibre and FODMAP-restricted diet in the management of constipation and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41(12): 1256-1270.

- Hetterich L, Zipfel S, Stengel A: Gastrointestinal somatoform disorders. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2019; 87(9): 512-525.

- Ford AC, Lacy BE, Harris LA, et al: Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG 2019; 114(1): 21-39.

- Hetterich L, Stengel A: Psychotherapeutic interventions in irritable bowel syndrome. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020; 11: 286.

- Beatty L, Lambert S: A systematic review of internet-based self-help therapeutic interventions to improve distress and disease-control among adults with chronic health conditions. Clinical Psychology Review 2013; 33(4): 609-622.

- Black CJ, Thakur ER, Houghton LA et al: Efficacy of psychological therapies for irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut 2020; 69(8): 1441-1451.

- Webb AN, Kukuruzovic RH, Catto-Smith AG, Sawyer SM: Hypnotherapy for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 4: CD005110.

- rouwel M, Farley A, Greenfield S et al: Systematic review, meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome, effect of intervention characteristics. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2021; 57: 102672.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(2): 10-15