Burnout is a symptom complex with the cardinal symptom of exhaustion as a response to prolonged emotional and interpersonal stress in the workplace. Multimodal therapy management is based on psychoeducation, sleep hygiene, understanding the illness, psychological risk factors, self-care, coping strategies, conflict resolution and social skills. As good patient care is based on a well-functioning practice team, burnout should be prevented through a positive organizational structure.

You can take the CME test in our learning platform after recommended review of the materials. Please click on the following button:

Burnt out, empty and powerless are the keywords that spring to mind when we think of burnout. First described in 1974 by the American psychotherapist Herbert J. Freudenberger, the problem mainly related to people in social professions [1]. He described burnout as a crisis of social workers who no longer felt able to maintain their previously high level of commitment. In the meantime, the disease is spreading. For a long time, there was no uniform definition of burnout. In ICD 10, the Z diagnoses were generally used, such as Z73.0 Burnout. In ICD 11, burnout was assigned to chapter 24. This includes factors that influence health or the use of health services. This includes the definition of burnout as a syndrome caused by chronic stress at work that has not been successfully managed. The reference to the professional context is important. A feeling of loss of energy and exhaustion, increasing mental distance from work or feelings of negativism or cynicism about work as well as reduced professional performance are perceived.

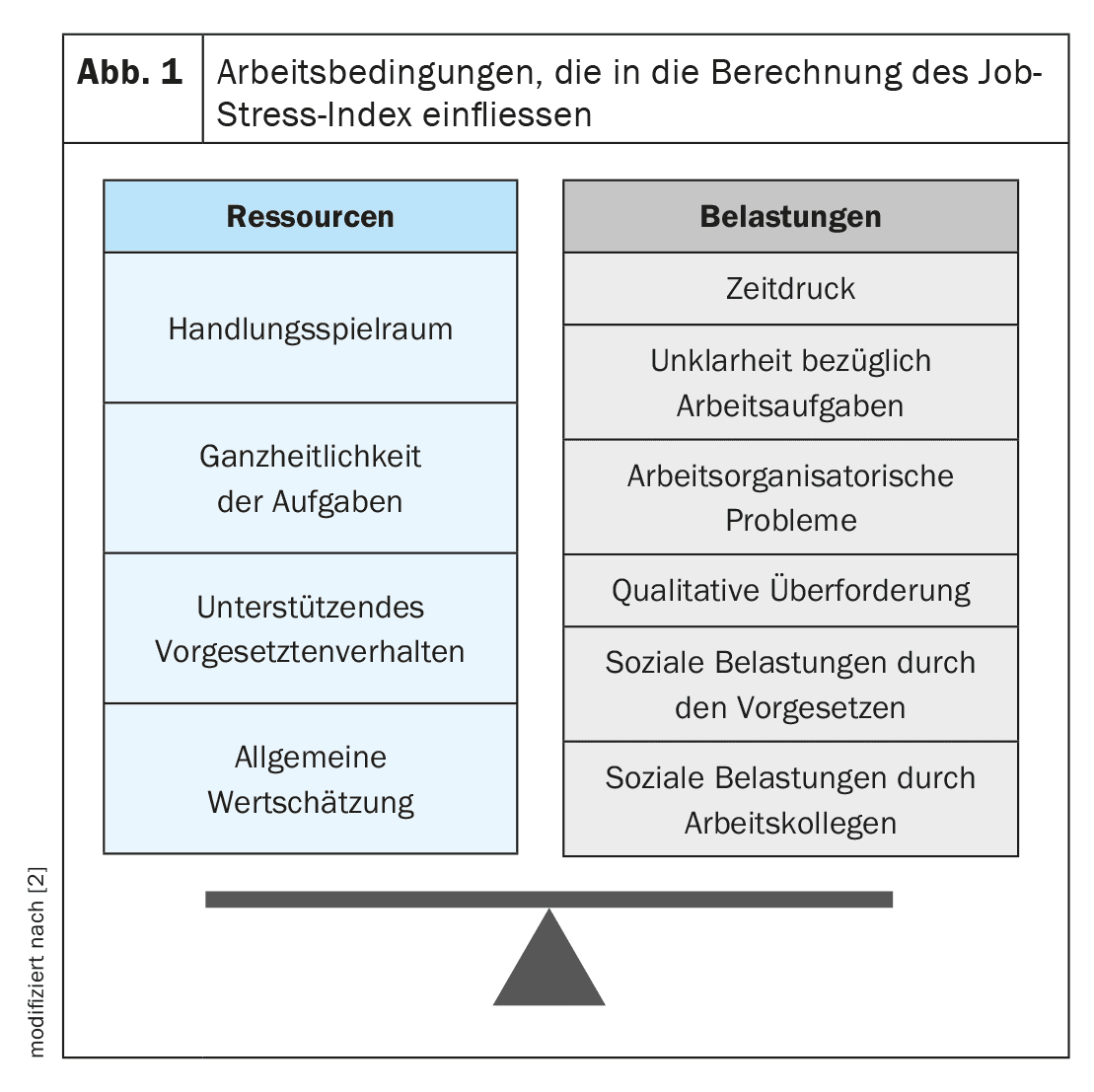

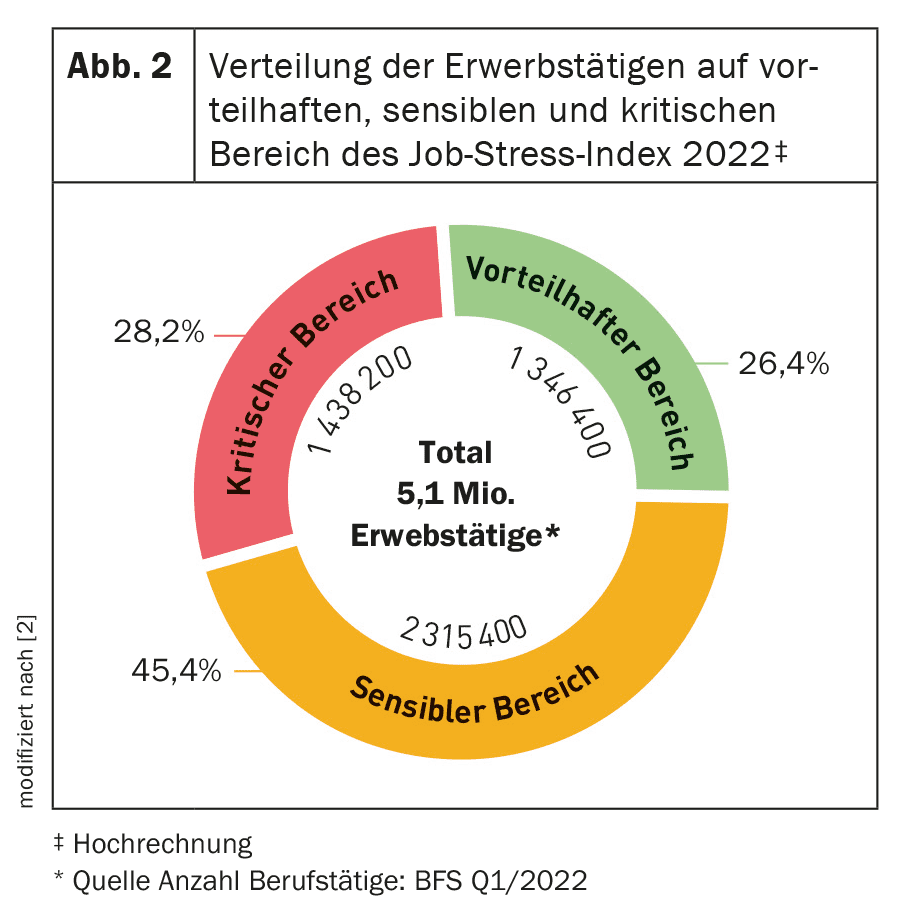

According to surveys, up to 1/3 of the working population today fulfill the criteria for burnout or a preliminary stage of burnout [1]. This corresponds well with the data collected in Switzerland. As part of Health Promotion Switzerland, the Job Stress Index 2020 found that almost 30% of employees are emotionally exhausted. The Job Stress Index shows the average ratio of work-related stress and resources of employees in Switzerland. Stress in the work context can be, for example, time pressure, conflicts or excessive demands. Certain characteristics of the working environment can make it easier to cope with these stresses and therefore represent resources for employees. These include, for example, freedom of action or appreciation (Fig. 1) [2]. The pandemic has further exacerbated the situation in 2020-2022. At 30.3%, the proportion of employees who feel emotionally exhausted exceeded the 30% mark for the first time since 2014. In addition, the proportion of employees whose job stress index was in the critical range was 28.2% (Fig. 2) [2]. What should not be underestimated: work-related stress accounts for 16% of the total costs of CHF 48 billion due to health problems [2].

The burnout spiral

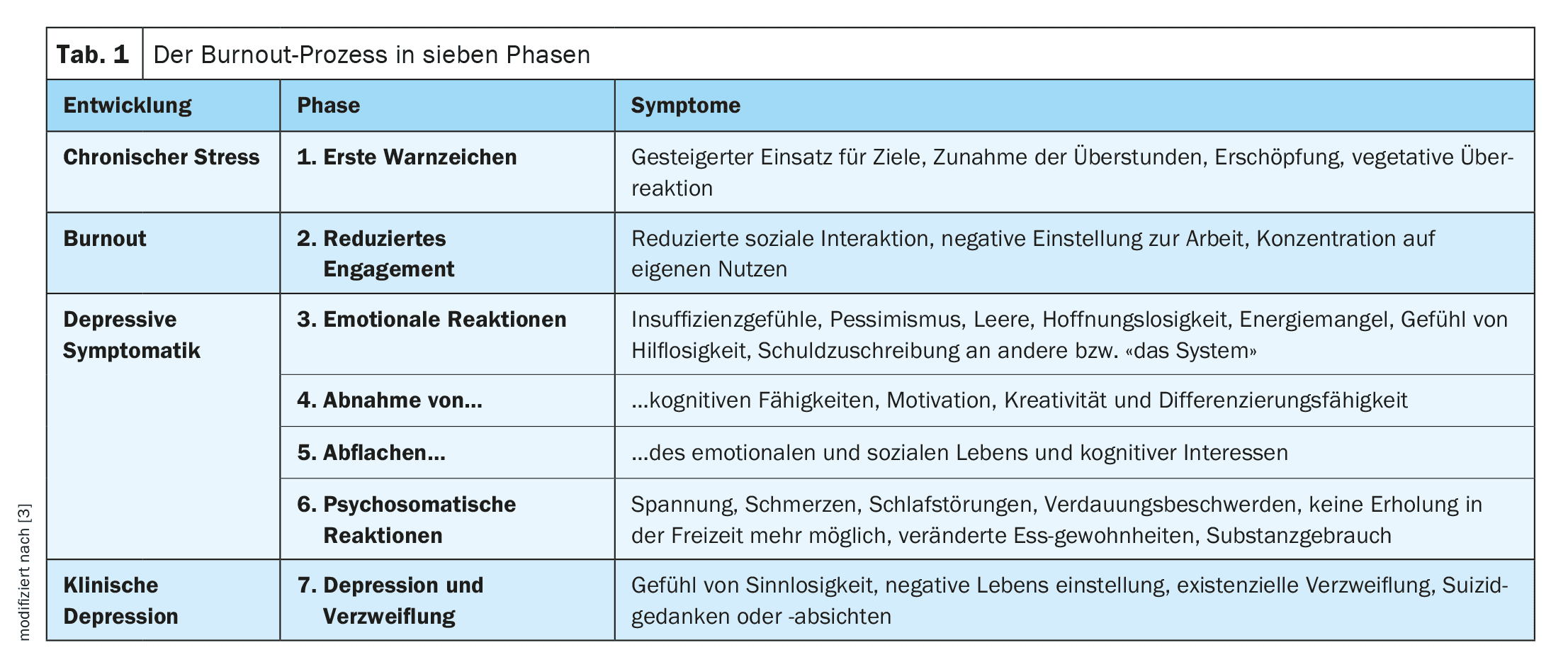

Burnout manifests itself clinically with the leading symptom of exhaustion in the context of various chronic psychosocial stresses against the background of a life-historically acquired increased readiness to cope with stress, certain personality variables and available coping strategies for dealing with stress [3]. Pathogenetically, the process is based on a complex interplay of personality traits and occupational environmental factors. People who overexert themselves at work appear to be at risk. This also includes authoritarian or compulsive personalities who are unable to hand over work or accept help for fear of losing control. In addition, the risk of burnout increases with high demands, little room for maneuver, little reward for achievements and little social support [3]. Burnout then develops in the form of a process with its diverse physical, emotional, cognitive and behavioral symptoms (Table 1) [3].

Diagnostics and differential diagnoses

There are no objective parameters for diagnosing burnout. The diagnosis is made clinically on the basis of the characteristic triad of symptoms consisting of

- Feeling of loss of energy and exhaustion (core symptom),

- increasing mental distance from work or feelings of negativism or cynicism about work,

- and reduced occupational performance.

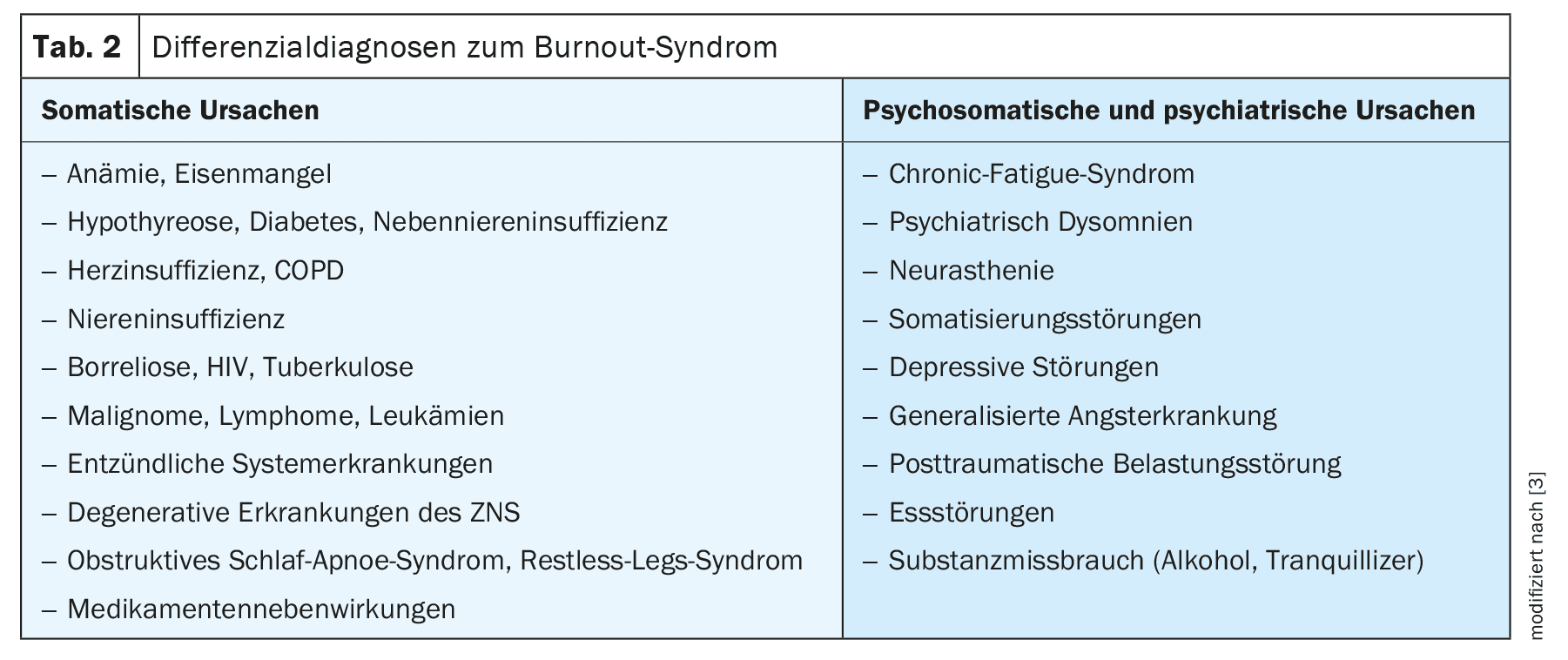

In terms of differential diagnosis, somatic as well as psychosomatic and psychiatric causes should be looked at more closely (Table 2) [3]. The cardinal symptom of exhaustion provides a point of reference. Somatic causes for the state of exhaustion must therefore be ruled out. A precise classification should also be made with regard to depression. In everyday clinical practice, the distinction between the two symptoms is often blurred. It has been shown that the greater the severity of burnout, the more likely it is that depression is also present. On the other hand, burnout is not synonymous with depression. A large Finnish study showed that depression could be detected in 20% of those examined with mild burnout and 53% with severe burnout. In contrast, only 7% of employees without burnout were found to be depressed [4].

Effects on everyday practice

The quality of life of those affected suffers considerably. They are caught in a vicious circle of depressed mood or various symptoms experienced as physical or psychological, reduced work performance, inner resignation and increasing conflicts. In addition to psychotherapeutic support, de-escalating measures in the workplace are indicated. Important factors for health and productivity are a safe and trusting working environment and activities that are experienced as meaningful. It is not just the intensity of work that promotes burnout. Above all, it is the subjective experience of stress. For example, frequent changes, multitasking and pressure to perform are perceived as stressful – an apt summary of the day-to-day work of many medical assistants. External influences can rarely be influenced. What employers can control, however, are recognition and appreciation, job security and professional development opportunities. Participation in decision-making processes also appears to be a protective factor. The basis for this is comprehensive information for employees, consideration of their point of view, the opportunity to agree or disagree, standardized decision-making processes, friendly interaction and a relationship of trust with employees [5].

Prevention through a positive corporate culture

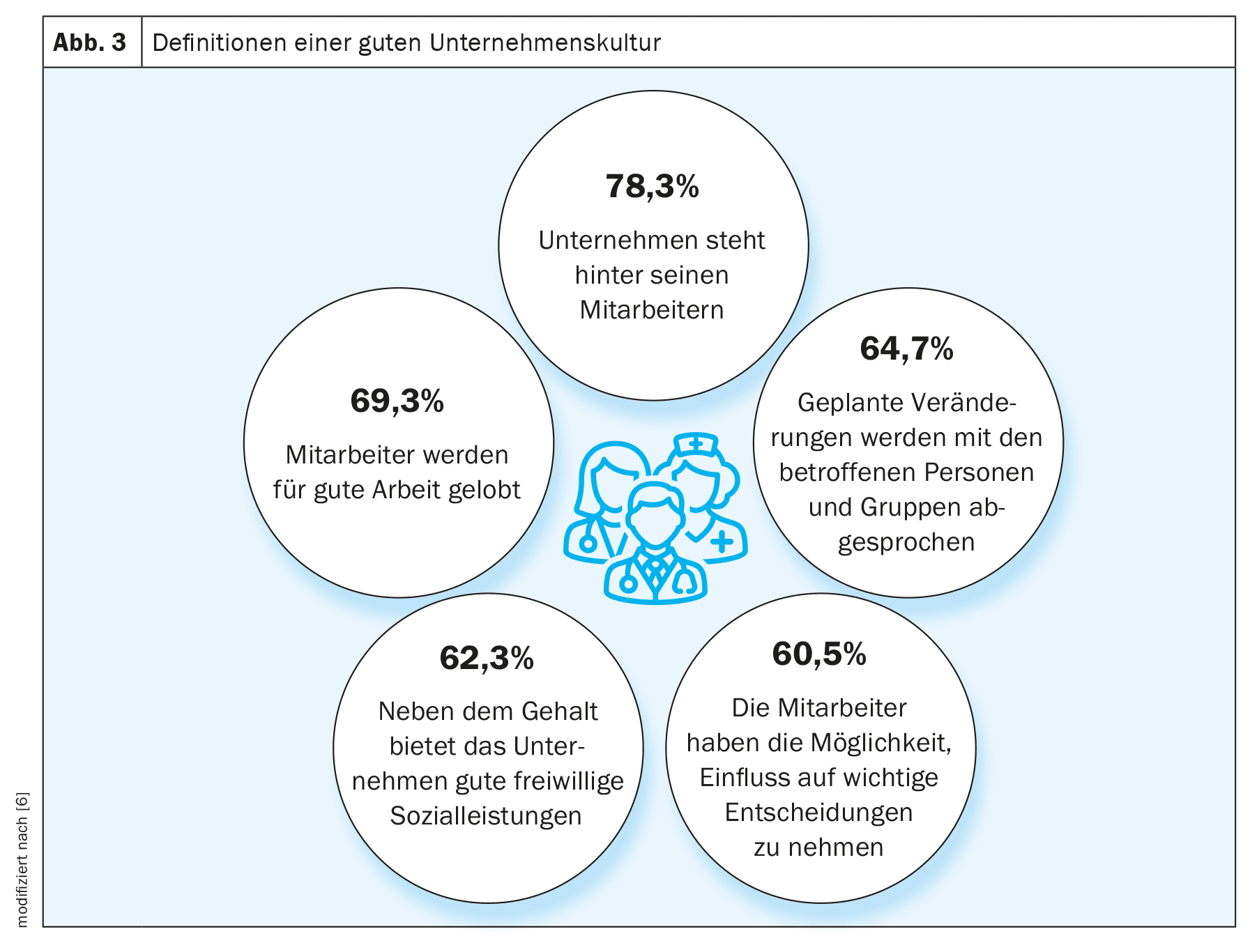

The basis for good patient care has always been a well-functioning team anyway. However, a Forsa survey showed that the younger generation in particular is very willing to change jobs. The main reasons for wanting to change jobs were a salary that was perceived as too low (49%) and a high level of stress (42%). 27% of respondents also stated dissatisfaction with the management culture. Awareness of mental health has risen sharply in recent years. And this in turn has an impact on the working environment. The absenteeism report by the Scientific Institute of the AOK shows that 27.5% of respondents who rated their corporate culture negatively were also dissatisfied with their health. This was three times as many as those who rated their corporate culture positively [6]. But what makes a good corporate culture? Above all, it is a company that stands behind its employees, line managers who praise good work and employers who discuss planned changes with those affected (Fig. 3) [6].

These views are supported by the assumptions of the sociologist Prof. Aaron Antonovsky. According to his theories, comprehensible processes and decisions have a salutogenic effect. Events are experienced as coherent by the team if they can understand what is happening. A good working atmosphere prevails when the demands on the individual can be met, support is available in the event of difficulties and work is fundamentally solution-oriented. Employees want to be seen, valued and included as human beings.

The workforce is a valuable resource that should be protected. This includes physical and mental fitness, mental resilience and the ability to regenerate. Health-promoting and preventive measures pay off. Analyses show that measures in the area of occupational health management generate an average of almost CHF 3 for every CHF invested. In the case of measures to promote mental health, the figure is even around CHF 5. How do you achieve this? With the help of a participation-oriented approach. Employee surveys and open communication offer opportunities to obtain information quickly. For employees, regular systematic reflection on personal goals and values in a professional context makes sense. Participation in supervision and self-awareness groups can also help to balance the work-life balance.

Multimodal therapy management

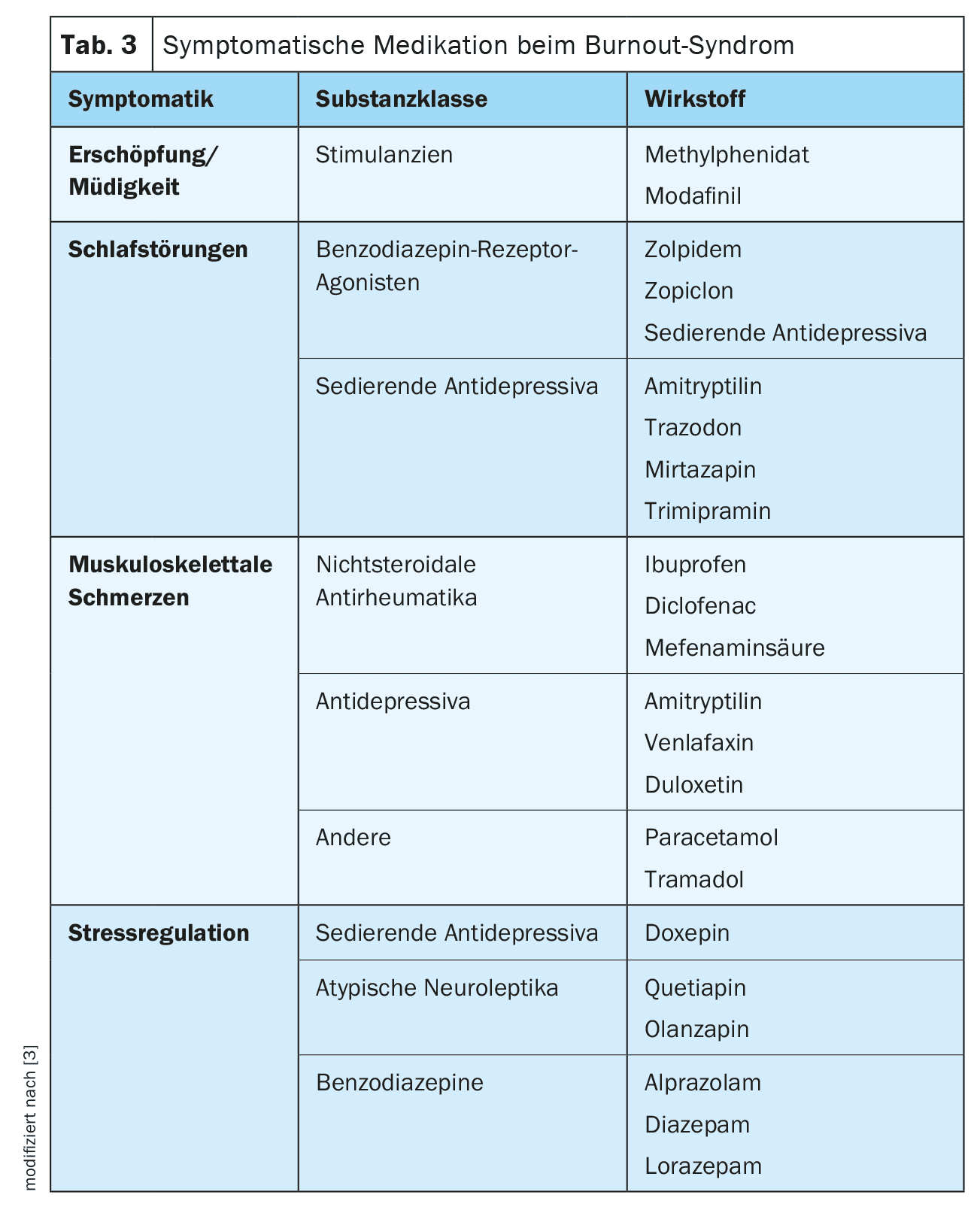

Therapy for burnout is about aligning individual possibilities and expectations with the external framework conditions [1]. This should always be done in a multimodal setting. Psychoeducation, sleep hygiene, understanding the illness, psychological risk factors, self-care, coping strategies, conflict resolution and social skills are taught. Depending on the severity and duration of the symptoms, it can be treated with improved self-management, under the guidance of a trained coach, with the support and guidance of a GP, in an actual outpatient psychotherapeutic setting or in a specialized psychosomatic hospital ward [3]. Somatic and/or psychological comorbidities must be treated lege artis. Psychosocial stress outside the world of work should also be addressed and treated accordingly. In addition, adjuvant therapies such as sport, relaxation and body therapies as well as mindfulness exercises can help. As places with psychotherapists are rare, digital health applications (DiGAs) can bridge the initial period. Temporarily and in individual cases, it may be useful to consider pharmacological concomitant therapy (Table 3) [3].

Take-Home-Messages

- Burnout is a symptom complex with the cardinal symptom of exhaustion as a response to prolonged emotional and interpersonal stress in the workplace.

- Chronic stress disorder has far-reaching somatic, psychiatric, social and economic consequences for the person concerned, their immediate environment and society.

- Multimodal therapy management is based on psychoeducation, sleep hygiene, understanding the illness, psychological risk factors, self-care, coping strategies, conflict resolution and social skills.

Literature:

- www.neurologen-und-psychiater-im-netz.org/psychiatrie-psychosomatik-psychotherapie/stoerungen-erkrankungen/burnout-syndrom (last accessed on 20.08.2024).

- https://friendlyworkspace.ch/de/themen/arbeitsbedingter-stress/studie-job-stress-index (last accessed on 20.08.2024).

- von Känel R: The burnout syndrome: a medical perspective. Practice 2008; 97: 477-487.

- Ahola K, Honkonen T, Isometsä E, et al: The relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders-results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Affect Disord 2005; 88: 55-62.

- Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, et al: Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup Environ Med 2003; 60(10): 779-783.

- www.wido.de/publikationen-produkte/buchreihen/fehlzeiten-report/2016 (last accessed on 20.08.2024).

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2024; 34(6): 6–9