Inhalation therapy for COPD is based on symptoms and exacerbation frequency. Basic therapy for COPD is based on long-acting bronchodilators. Inhaled corticosteroids are used only under certain conditions.

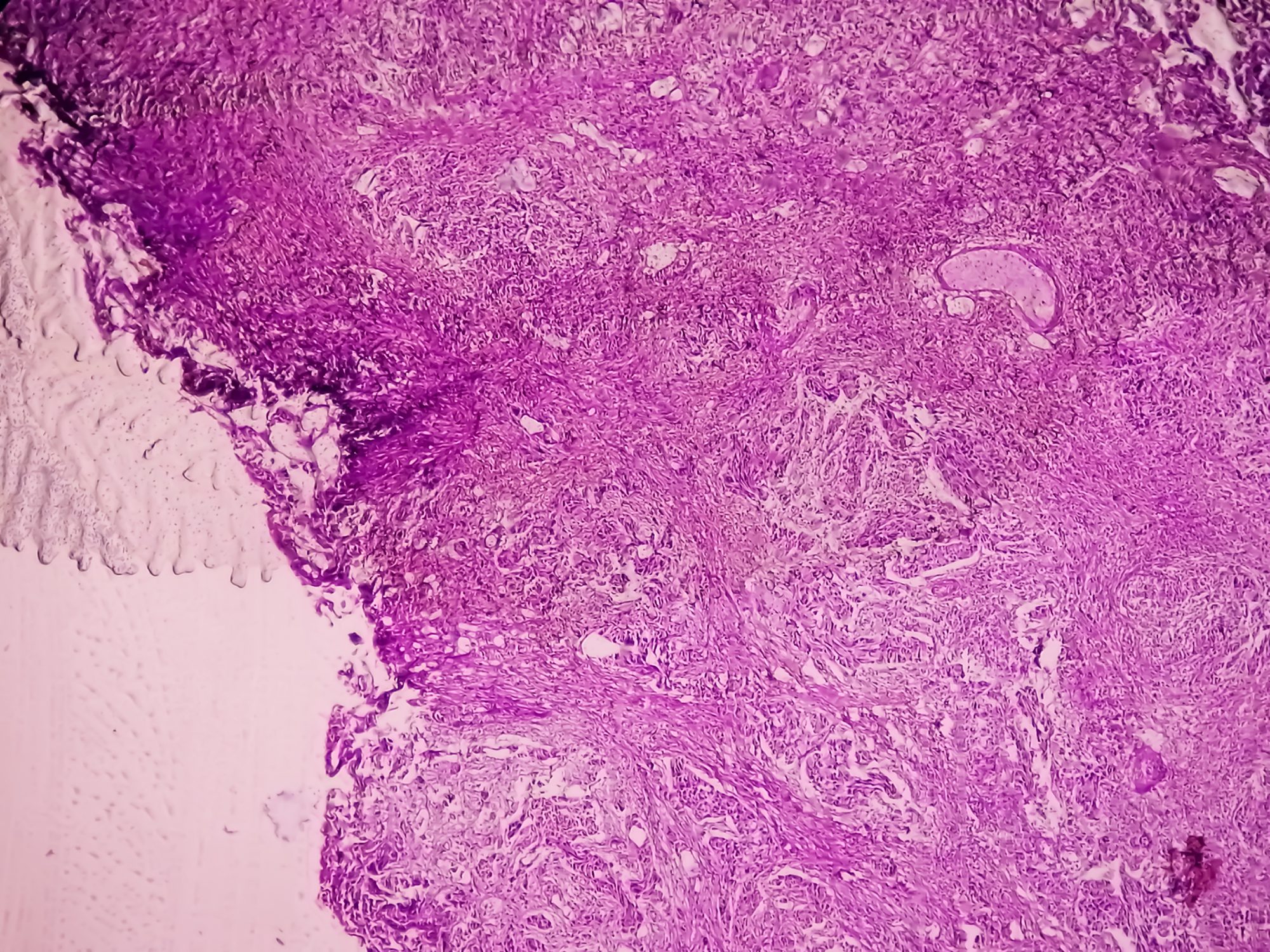

COPD is one of the most common diseases in the general population, for Switzerland the prevalence is 7%, in family practice 5.6% to 7% [1–3]. The disease is characterized by chronic obstruction and inflammation of the small airways with consecutive fibrotic remodeling and development of emphysema. COPD is associated with increasing morbidity and mortality [4,5]. One of the mainstays of treatment for COPD is inhaled therapy, which reduces symptoms, frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improves exercise capacity and quality of life. However, an effect on mortality has so far only been shown in post-hoc analyses [6]. In recent years, on the one hand, many new active substances with corresponding new inhalation devices have come onto the market, and on the other hand, the recommendations for the stage-appropriate use of inhalation therapy have changed fundamentally. The inhalatives can be divided into three substance classes and two groups depending on the mechanism of action (Tab. 1).

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilators lead to improvement in lung function and reduction in dynamic hyperinflation, leading to an increase in exercise capacity. Short-acting bronchodilators (duration of action 4-6 hours, depending on the preparation) are used in particular as moist inhalation, mainly in the context of exacerbations of COPD or in concomitant diseases such as bronchiectasis. In addition, they are often prescribed as symptom-relieving on-demand medications. Long-acting bronchodilators (duration of action 12-24 hours, depending on the preparation) are generally used in the long-term treatment of COPD (Table 2).

Beta(β)-2-mimetics: Agents of this substance class bind to the adrenergic β-2-receptors, increase the intracellular cAMP concentration and lead to a relaxation of the bronchial smooth muscle, which counteracts chronic bronchoconstriction. The adrenergic mechanism of action also explains the most common side effects – resting tachycardia and tremor. Hypokalemia, due to a shift of potassium to intracellular, can be aggravated by concomitant use of thiazide diuretics and lead to cardiac arrhythmias [7]. A meta-analysis associated an increased cardiovascular risk profile (myocardial ischemia, decompensated heart failure, arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death) with β-2-mimetics [8]. Expression of β-2-receptors in cardiac myocytes, as well as the aforementioned hypokalemia, may play a role; the exact mechanism remains unclear. However, numerous studies from recent years with all β-2-mimetics approved for the treatment of COPD could not substantiate this observation [9–13], so that topical β-2-mimetics should not be withheld from patients with known cardiovascular disease. Another concern due to potential interactions is concomitant use with β-blockers, which are less commonly prescribed in patients with COPD and cardiovascular disease despite a given indication [14]. However, cardioselective β-blockers (metoprolol, bisoprolol, and nebivolol) have no effect on the therapeutic effect of inhaled β-2-mimetics [15], so they are still recommended in the treatment of heart failure or after myocardial infarction, even in patients with COPD [14].

Anticholinergics: The second class of substances with a bronchodilator effect are the anticholinergics, which act by blocking the M3 acetylcholine receptor on the smooth muscle cells of the bronchi. Dry mouth is the most common side effect. Urinary retention has been reported in the literature as a clinically relevant side effect with the use of both short-acting and long-acting anticholinergics in men [16]. This particularly affects patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia or lower urinary tract symptoms. Monotherapy is not contraindicated despite the presence of these risk factors, but patients should be warned of the risk of urinary retention. Concurrent therapy (SAMA+LAMA) additionally increases the risk of urinary retention in this patient group and should be avoided [17].

Combination therapy: combination therapy with a long-acting β-2-mimetic and a long-acting anticholinergic (LABA+LAMA) results in synergistic improvement in lung function and quality of life, as well as reduction in exacerbation frequency compared with monotherapy [18–21]. Combination therapy is recommended for patients with persistent symptoms despite monotherapy or for exacerbation prophylaxis (see below). Currently, several drug combinations are approved with different inhalation devices (Table 2).

Inhaled corticosteroids

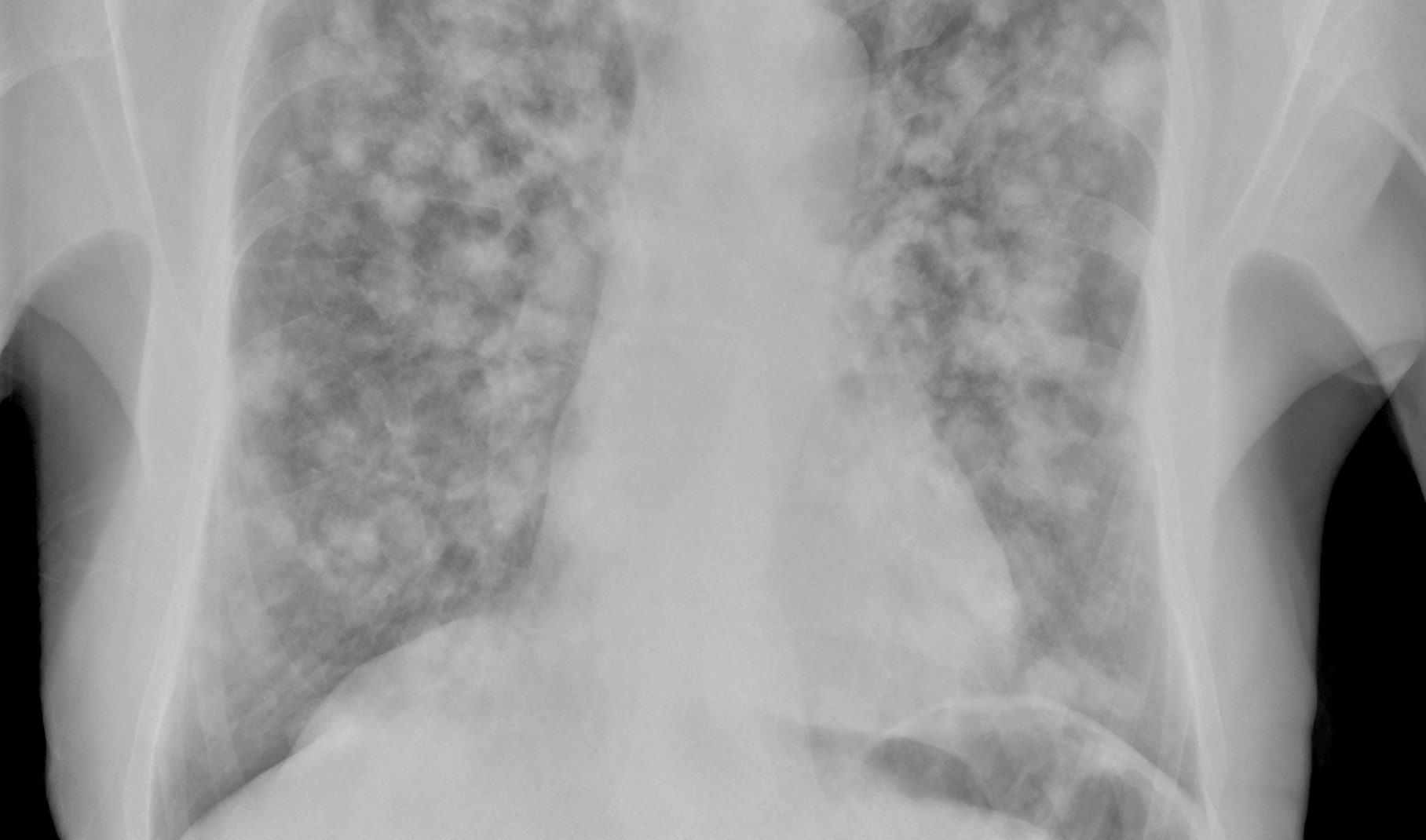

The use of inhaled corticosteroids is intended to treat chronic inflammation of the small airways. However, inhaled corticosteroids are not recommended as monotherapy for the treatment of COPD because they have not shown an effect on lung function decline or mortality [22]. In contrast, as a combination with long-acting β-2-mimetics (LABA+ICS) (Table 2), an improvement in lung function and reduction in exacerbation frequency was demonstrated in patients with ≥1 exacerbation/year [23]. However, whether the effect was due to the inhaled corticosteroids alone remains an open question [24]. A comparable effect on exacerbation rate was observed with long-acting anticholinergics alone [25] and combination therapy with LABA+LAMA leads to significantly improved lung function, exacerbation rate and quality of life compared to treatment with LABA+ICS [21]. Thus, the place of inhaled corticosteroids in the treatment of COPD has been questioned in recent years and their use has been reduced because of side effects, especially pneumonia.

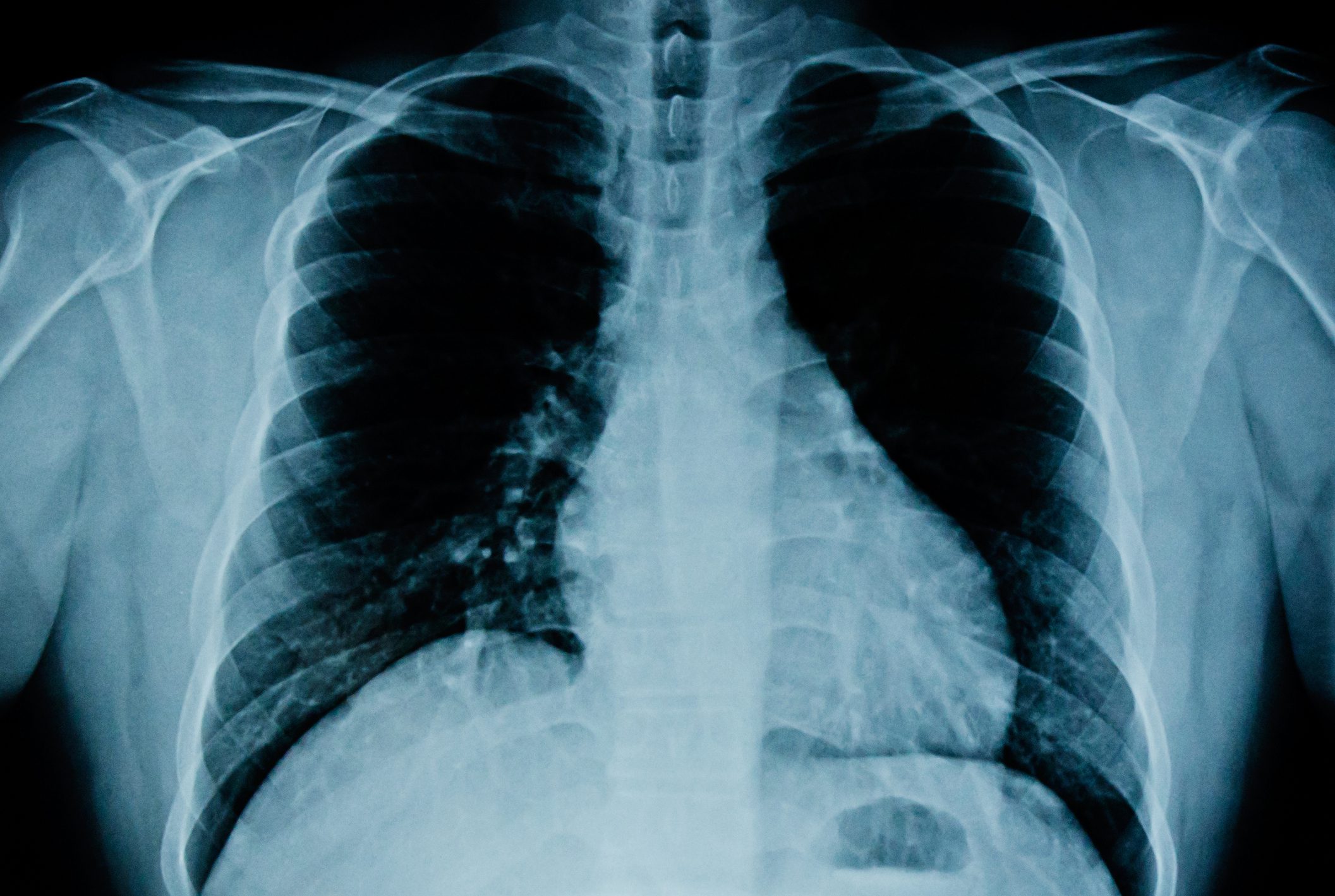

The increased incidence of pneumonia is explained by the immunosuppressive effect of corticosteroids with increased local concentration in the lungs. According to the most recent studies, it does not seem to be a class effect – the highest incidence was observed as a side effect of fluticasone propionate therapy – but a stronger immunosuppressive potency [26], possibly differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics may further enhance this effect. Other common side effects include hoarseness and oral candidiasis, but these can be avoided with proper inhalation technique and simple prophylactic measures (pre-inhalation chamber, mouth rinse, brushing teeth, eating or drinking after inhalation).

Principles of inhalation therapy

In the past, inhalation therapy was prescribed depending on the extent of airway obstruction. For example, inhaled corticosteroids were recommended starting at GOLD stage 3 (severe obstruction). With the introduction of the new risk classification in 2011, it was then possible for patients with moderate obstruction but increased symptoms or exacerbations to receive inhaled corticosteroids. Since 2017, risk stratification is performed regardless of the severity of the obstruction. Thus, only symptoms (dyspnea) and exacerbation frequency are considered in the indication for the different inhalatives. Spirometry is used to establish the diagnosis in the presence of appropriate clinical signs (dyspnea, cough, sputum) and to assess the severity of obstruction (Fig. 1).

The current principles of inhalation therapy are based on the additive effect of dual bronchodilation and on new knowledge about inhaled corticosteroids. Basic therapy still includes a long-acting bronchodilator. The indication for initial combination therapy or for an extension of therapy is based on the symptoms and the frequency of exacerbations (i.e., the risk class) (Fig. 2). Inhaled corticosteroids are reserved for patients with persistent symptoms and/or recurrent exacerbations despite combination therapy with two bronchodilators (see below for exceptions). Triple therapy can achieve a reduction in exacerbations and hospitalizations [27,28].

Discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids: even before the current treatment recommendations were introduced, 45% and 54% of COPD patients in GOLD stage 1 and 2, respectively, were receiving inhaled corticosteroids without indication [29]. In many COPD patients with a long history and largely stable course, inhaled corticosteroids (especially as combination therapy LABA+ICS) are often continued without reevaluation of the indication. 75% of these patients have not had an exacerbation in the past year, so inhaled corticosteroids can be discontinued in low to moderate doses, phased out in high doses, and bronchodilator therapy can be supplemented with a second agent if necessary. Patients with an exacerbation in the last year who are treated only with a LABA+ICS combination should be switched to LABA+LAMA [30,31]. Patients with frequent exacerbations (≥2/year) despite triple therapy should be referred for specialist evaluation of other treatment options (noninvasive ventilation, immunomodulatory therapy with azithromycin or roflumilast). Outpatient or inpatient pulmonary rehabilitation is also part of the standard of care [6].

Inhaled corticosteroids in special situations: Continuing therapy with inhaled corticosteroids is not recommended in COPD patients with an asthmatic component (asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, ACOS). (Tab. 3), When there are ≥2 exacerbations per year or when a blood eosinophilia is >0.3 G/l (>4%) is justified, as such patients have an increased risk of exacerbation after discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids [32,33]. Figure 3 is intended to aid in decision making regarding inhaled corticosteroids.

Drug selection: The effect of the different drugs in the respective substance class is comparable. Some are administered twice daily, some only once daily – the choice should be individualized according to patient preference and need. Correct inhalation technique is important for therapeutic success, so sometimes it is the inhalation device rather than the active ingredient that leads the way in drug selection.

Take-Home Messages

- Spirometry together with appropriate clinical signs (shortness of breath, cough, sputum) is used to diagnose COPD.

- Inhalation therapy of COPD is based on the risk class, i.e. according to the symptomatology and exacerbation frequency: basic therapy of COPD with long-acting bronchodilators (β-2-mimetics and anticholinergics), inhaled corticosteroids only in case of additional asthmatic component, blood eosinophilia of >0.3 G/l (>4%) or recurrent exacerbations despite extended dual bronchodilator therapy.

- Inhaled corticosteroids can be discontinued in about 80% of patients already treated with them.

Literature:

- Bridevaux PO, et al: Prevalence of airflow obstruction in smokers and never-smokers in Switzerland. Eur Respir J. 2010; 36(6): 1259-1269.

- Kassenärztliche Vereinigung Sachsen-Anhalt: The 100 most frequent diagnoses in practices of general practitioners, general practitioners, physicians without a regional designation, general practitioner internists, 1st quarter 2018, www.kvsa.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Bilder/Content/Praxis/Verordnung/Report_Allgem_20181.pdf, last accessed 16.10.2018

- Federal Health Interview Surveillance (GBE), www.gbe-bund.de, last accessed Oct. 16, 2018.

- Lozano R, et al: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380(9859): 2095-2128.

- Vos T, et al: Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012; 380(9859): 2163-2196.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2018. https://goldcopd.org, last accessed 16.10.2018

- Lipworth BJ, et al: Hypokalemic and ECG sequelae of combined beta-agonist/diuretic therapy. Protection by conventional doses of spironolactone but not triamterene. Chest 1990; 98(4): 811-815.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE: Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest 2004; 125(6): 2309-2321.

- Campbell SC, et al: Cardiac safety of formoterol 12 microg twice daily in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2007; 20(5): 571-579.

- Calverley PM, et al: Cardiovascular events in patients with COPD: TORCH study results. Thorax 2010; 65(8): 719-725.

- Worth H, et al: Cardio- and cerebrovascular safety of indacaterol vs formoterol, salmeterol, tiotropium and placebo in COPD. Respir Med 2011; 105(4): 571-579.

- McGarvey L, et al: One-Year Safety of Olodaterol Once Daily via Respimat® in Patients with GOLD 2-4 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Results of a Pre-Specified Pooled Analysis. COPD 2015; 12(5): 484-493.

- Brook RD, et al: Cardiovascular outcomes with an inhaled beta2-agonist/corticosteroid in patients with COPD at high cardiovascular risk. Heart 2017 Oct; 103(19): 1536-1542.

- Petta V, et al: Therapeutic effects of the combination of inhaled beta2-agonists and beta-blockers in COPD patients with cardiovascular disease. Heart Fail Rev 2017; 22(6): 753-763.

- Salpeter SR, et al: Cardioselective beta-blockers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Respir Med 2003; 97(10): 1094-1101.

- Stephenson A, et al: Inhaled anticholinergic drug therapy and the risk of acute urinary retention in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171(10): 914-920.

- Vande Griend JP, Linnebur SA: Inhaled anticholinergic agents and acute urinary retention in men with lower urinary tract symptoms or benign prostatic hyperplasia. Ann Pharmacother. 2012; 46(9): 1245-1249. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R282. Epub 2012 Jul 31.

- Tashkin DP, et al: Formoterol and tiotropium compared with tiotropium alone for treatment of COPD. COPD 2009; 6(1): 17-25.

- Dhillon S: Tiotropium/Olodaterol: A Review in COPD. Drugs 2016; 76(1): 135-146.

- Wedzicha JA, et al: Analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations with the dual bronchodilator QVA149 compared with glycopyrronium and tiotropium (SPARK): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1(3): 199-209. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70052-3. epub 2013 Apr

- Wedzicha JA, et al: Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(23): 2222-2234.

- Yang IA, et al: Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Jul 11; (7): CD002991. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002991.pub3

- Nannini LJ, et al: Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus inhaled corticosteroids alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 30 (8): CD006826.

- Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P: Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Sep 12; (9): CD006829.

- Wedzicha JA, et al: The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177(1): 19-26. epub 2007 Oct 4.

- Janson C, et al: Pneumonia and pneumonia related mortality in patients with COPD treated with fixed combinations of inhaled corticosteroid and long acting β2 agonist: observational matched cohort study (PATHOS). BMJ 2013 May 29; 346: f3306.

- Lipson DA, et al: Once-Daily Single-Inhaler Triple versus Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(18): 1671-1680.

- Papi A, et al: Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 391(10125): 1076-1084.

- Jochmann A, et al: General practitioner’s adherence to the COPD GOLD guidelines: baseline data of the Swiss COPD Cohort Study. Swiss Med Wkly 2010 Aug 9; 140. pii: 10.4414/smw.2010.13053.

- Magnussen H, et al: Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(14): 1285-1294.

- Cataldo D, et al: Overuse of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: five questions for withdrawal in daily practice. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018; 13: 2089-2099.

- Global Initiative for Asthma and Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease, 2017. Diagnosis and initial treatment of asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap. Updated April 2017.

- Watz H, et al: Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4(5): 390-398.

- Desktop helper 6: Evaluation of appropriateness of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) therapy in COPD and guidance on ICS withdrawal, %3A+Evaluation+of+appropriateness+of+inhaled+corticosteroid+%, last accessed 10/16/2018.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(11): 8-14