In October, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published its 2024 guidelines for the treatment of high blood pressure and hypertension. At the swissESCupdate, Dr. Lucas Lauder from the University Hospital Basel, one of the authors of the updated guidelines, reported on the most important changes.

The most obvious change in the guidelines is that they are now only published by the ESC. The European Society of Hypertension (ESH) is no longer involved, having published its own guidelines last year. The American Society will follow with its guidelines next year, which means “we will have a variety of guidelines on the market,” as Dr. Lauder explained. A second major change in this version is the name: it is not just a guideline for hypertension, but a guideline on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension .

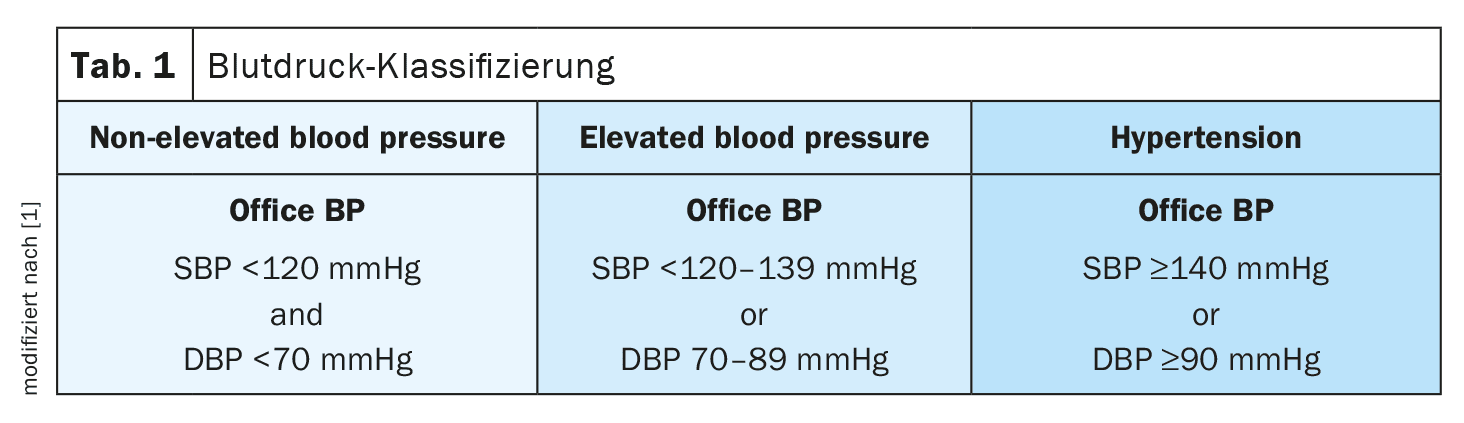

In terms of content, the definition and classification of high blood pressure have changed. They have been simplified: instead of seven different classes of high blood pressure as before, there are now only three categories to remember. The definition of hypertension has not changed. Hypertension is still defined as an office blood pressure (i.e. a blood pressure under practical conditions) of ≥140 mmHg (systolic) or ≥90 mmHg (diastolic). Non-elevated blood pressure is now defined as office BP <120 mmHg (systolic) or <70 mmHg (diastolic) and in between are patients with elevated blood pressure, defined as office BP of 120-139 mmHg (systolic) or 70-89 mmHg (diastolic) (Table 1) [1].

The idea behind this is to raise awareness and prevent patients from becoming hypertensive in the first place. It is an approach to preventively treat patients before they become hypertensive and is primary prevention, not just secondary prevention, explained the cardiologist. “If it is not possible to measure the office BP, the value can be set 5-10 mmHg higher. However, the guidelines recommend the use of standardized blood pressure.”

Aim to prevent cardiovascular events

There are two reasons for the new concept of elevated blood pressure: “First of all, we have to recognize that blood pressure is different for each individual patient and most patients have different optimal blood pressure values. That’s why the guidelines don’t define a single value as optimal,” said Dr. Lauder. For example, women generally have lower blood pressure at a younger age than men, so the optimal blood pressure for a female patient is different than for a male patient. Second, a large burden of cardiovascular events is related to elevated blood pressure levels: In a meta-analysis, 30% of disability adjusted life years ( DALYs) lost related to cardiovascular disease occurred in individuals with SBP of 115-140 mmHg [2]. It is therefore not a question of treating every patient with elevated blood pressure, but of identifying patients at very high cardiovascular risk and treating these patients to prevent cardiovascular events.

Lifestyle improvement measures make sense for every patient. High-risk individuals with elevated blood pressure should be treated in this way to avoid the need for pharmacotherapy. However, if blood pressure is still >130/80 mmHg after 3 months of lifestyle intervention, patients with elevated blood pressure who are at high or very high cardiovascular risk should receive antihypertensive drug therapy.

This risk-based approach is not entirely new. It is a concept that was already introduced in the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines, in which patients with cardiovascular disease, particularly coronary heart disease, should be treated if their blood pressure is above 130/85 mmHg. The 2023 ESH guidelines pick up on this and also recommend drug treatment for patients with a history of cardiovascular disease if their blood pressure is in the high normal range (SBP ≥130 or DBP ≥80 mmHg).

Gender-specific risk modifiers

The first step is to clarify whether the patient already has an established pre-existing condition: “Does he suffer from cardiovascular disease, moderate to severe chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure, diabetes with moderate organ damage or familial hypercholesterolemia? Because these patients have a high cardiovascular risk. Therefore, it probably makes sense to treat them with pharmacological therapy,” said Dr. Lauder. If patients do not have any of these diseases, the guidelines recommend calculating cardiovascular risk using SCORE2 or SCORE2-OP: If the cardiovascular risk is <5%, there is nothing to do apart from lifestyle measures. If the cardiovascular risk is high, i.e. ≥10%, the guidelines recommend lifestyle measures. If blood pressure is still ≥130/80 after 3 months of lifestyle measures, pharmacological therapy should be initiated. For patients who are between 5 and 10%, it is now indicated to look for common risk modifiers and gender-specific risk modifiers.

Gender-specific risk modifiers include gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preterm delivery, pre-eclampsia, one or more stillbirths and recurrent miscarriages. They should be considered to better classify individuals with elevated blood pressure and borderline 10-year CVD risk (5% to <10% risk). Common risk modifiers (high-risk ethnicity, family history of premature atherosclerotic CVD, socioeconomic disadvantage, inflammatory autoimmune diseases, HIV, and severe mental illness) should be considered to upclassify individuals with elevated blood pressure and borderline 10-year CVD risk.

If a risk-based decision on antihypertensive treatment for individuals with elevated blood pressure remains uncertain after considering risk modifiers, measurement of CAC score, carotid or femoral peaques by ultrasound, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin or B-type natriuretic peptide biomarkers, or arterial stiffness by pulse wave velocity may be considered to improve risk stratification in patients with borderline elevated 10-year CVD risk after shared decision making and consideration of cost.

For patients with elevated blood pressure at high or very high risk or patients with hypertension, a treatment goal is initially set. The optimal treatment target has not changed from the previous guidelines: SBP target range is 120-129 mmHg, DBP 70-79 mmHg. However, the guidelines emphasize two key concepts: “First, we should always consider frailty and not age, because we know that a very old patient can be fit but a younger patient can be very frail. Normally common sense is sufficient for assessment, but if we need help, the guidelines recommend using the clinical frailty score (CFS). The second concept is ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable), provided the patient tolerates the treatment.”

With regard to lifestyle interventions, it is recommended to increase potassium intake if it is very low. If sodium intake is very high, it is important to optimize weight and physical activity and, of course, limit alcohol consumption. In terms of physical activity and exercise, it has long been known that aerobic exercise is beneficial, but recent studies and meta-analyses have shown that dynamic or isometric exercise is even better at lowering blood pressure in the long term. Therefore, the guidelines recommend a combination of aerobic exercise and isometric exercise.

Algorithm for pharmacotherapy

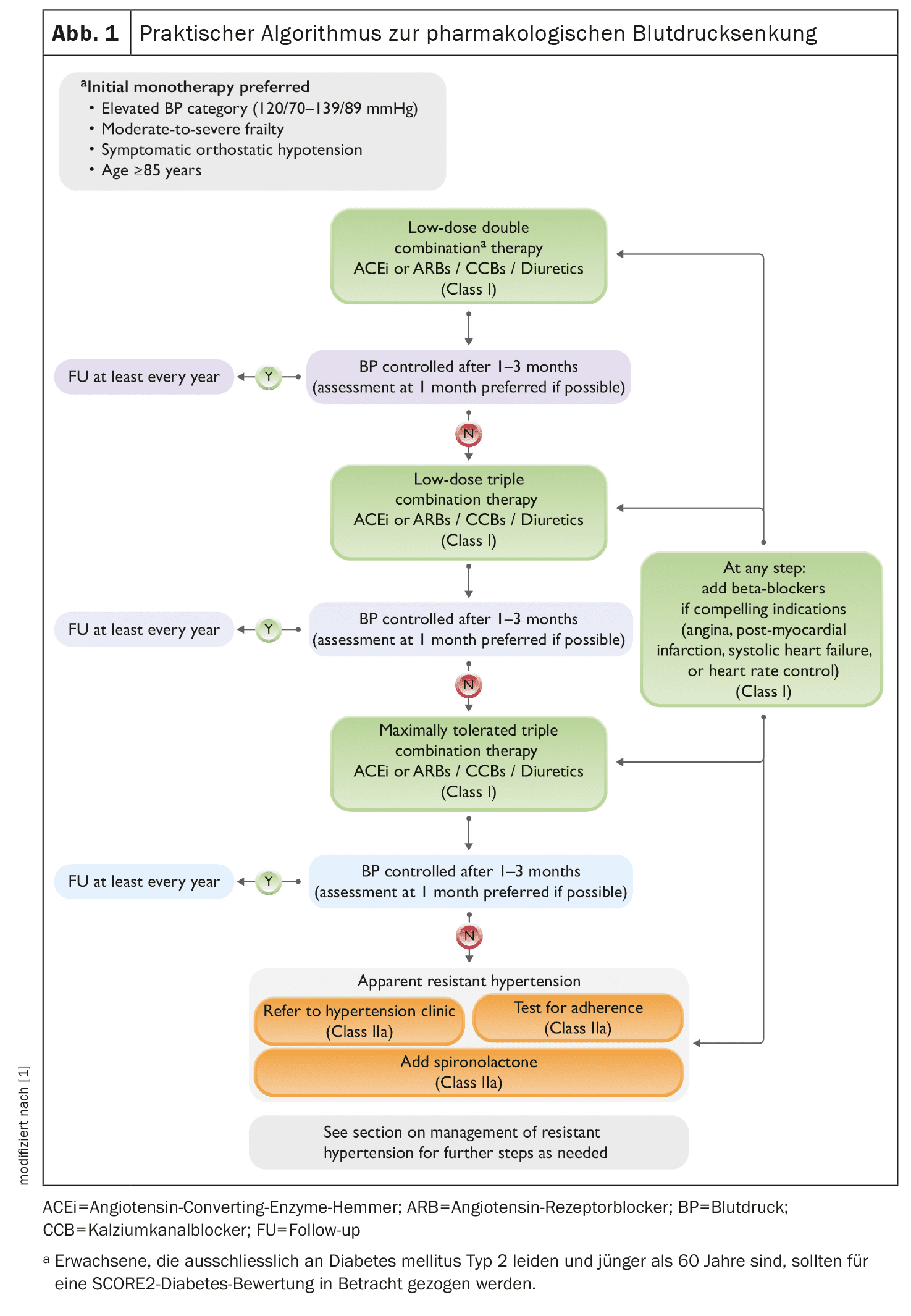

The algorithm for pharmacological therapy is similar to previous guidelines. In the first line, a low-dose combination of ACEi (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor) or ARB (angiotensin receptor blocker)/CCB (calcium channel blocker)/diuretics is recommended. Initial monotherapy should be preferred in patients with elevated blood pressure, as well as in patients with moderate to severe frailty and those who already have orthostatic hypotension or are ≥85 years of age. Beta-blockers are permitted if there are compelling indications (angina pectoris, post-myocardial infarction, systolic heart failure or heart rate control).

If blood pressure remains uncontrolled after 1-3 months, it is recommended to add a third drug at a low dose of ACEi or ARBs/CCBs/diuretics. The next step would be to increase the dose of the first three drugs before adding the fourth drug. Once blood pressure is under control, the patient should be monitored at least once a year by taking normal blood pressure readings in the office or, even better, by taking blood pressure readings outside the office (Fig. 1).

Patients with resistant hypertension, defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg in the office that remains above target despite three or more antihypertensive medications of different classes at maximum tolerated doses, including diuretics, must also be measured on an outpatient basis to ensure that it is not pseudoresistant or secondary hypertension. If resistant hypertension is confirmed, the guidelines recommend spironolactone as the fourth medication and a beta-blocker as the fifth medication if this has not yet been used. The further procedure should be discussed in a “joint risk-benefit discussion in which we ask the patient whether or not they prefer an intervention such as renal denervation or a drug”.

Dr. Lauder explained that renal denervation (RDN) is not recommended as a first-line antihypertensive treatment for hypertension due to the lack of adequately powered studies demonstrating safety and benefit for cardiovascular disease. In addition, RDN is not recommended for the treatment of hypertension in patients with moderately to severely impaired renal function (eGFR <40 ml/min/1.73m2) or secondary causes of hypertension until further evidence is available.

Take-Home-Messages

- Blood pressure measurements outside the doctor’s office are recommended to diagnose high blood pressure and to guide the titration of antihypertensive medication.

- For patients with “elevated blood pressure” (130-139/80-89 mmHg), there is a risk-based approach that takes (gender-specific) risk modifiers into account.

- In patients with high cardiovascular risk and a blood pressure ≥130/80 mmHg after 3 months of lifestyle measures, pharmacotherapy (usually as monotherapy) is recommended.

- It is recommended to titrate up from a low-dose double to a triple combination therapy before increasing the dose.

- Renal denervation is a treatment option in resistant hypertension and in certain patients taking <3 medications if they are in favor of renal denervation.

- The importance of joint decision-making is emphasized.

Congress: swissESCupdate.24

Literature:

- McEvoy JW, et al: 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension: Developed by the task force on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Stroke Organization (ESO). European Heart Journal 2024; 45(38): 3912-4018; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae178.

- Forouzanfar MH, et al: Global Burden of Hypertension and Systolic Blood Pressure of at Least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA 2017; 317(2): 165-182; doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19043.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(11): 38-40 (published on 25.11.24, ahead of print)

CARDIOVASC 2024; 23(4): 32–34